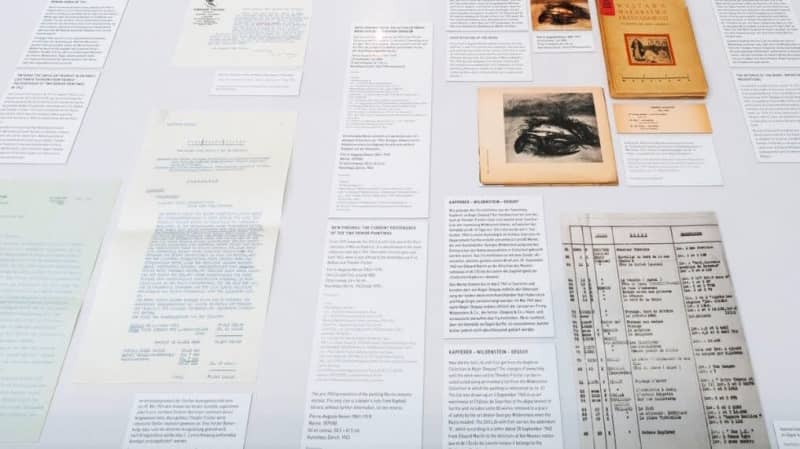

By Courtesy of Kunsthaus Zürich

The looting of artworks by the Nazi regime has long been a taboo subject, especially within the museum sector. Many European and North American museums have enriched their collections with paintings and sculptures of dubious provenance. Now, some of them hope to remedy this situation.

The looting of artworks by the Nazi regime has long been a taboo subject, especially within the museum sector. Many European and North American museums have enriched their collections with paintings and sculptures of dubious provenance. Now, some of them hope to remedy this situation.

The Kunsthaus Zürich is one such institution. The Swiss art museum recently announced that it will adopt a new provenance research strategy for its collection. Philipp M. Hildebrand, chair of the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft, which owns the collection, explains in a statement: "Our overriding objective must always be to review professionally the origins of the works we hold, and to enable just and fair solutions where there are substantiated indications of cultural property confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution."

To this end, the Kunsthaus has announced that it will work with an independent commission of international experts to determine whether artworks can be considered cultural property confiscated in the context of Nazi persecution. The museum has stated that it will subject its own collection and future acquisitions to this new provenance research strategy as a matter of priority.

This in-depth examination will focus on artworks made before 1945 that changed hands during the years when the Nazi regime was in power in Germany and other European regions (1933-1945). "We are aware that this will be a lengthy and complex process: ultimately, the history of each artwork involved is unique," states Philipp M. Hildebrand.

The proof is in the Emil Bührle Collection of paintings. This is housed in the new Kunsthaus building, designed by British star architect David Chipperfield, as of 2021. At the time, the Zürich museum had promised "real didactic support" to shed light on the dubious provenance and historical context surrounding this collection of French art, focusing notably on the Impressionists. The collection was acquired by Emil Bührle, a controversial arms manufacturer whose fortune was made from arms sales to Nazi Germany during World War II. He also took advantage of his close ties to Hitler's regime to acquire several masterpieces of painting that had belonged to Jewish art collectors or dealers. The presence of these works of art on the walls of the Kunsthaus has been described as an "affront" to the victims of Nazi looting by an independent panel of historians, reportsSwissinfo.

Some 600,000 looted artworks

Several European and North American museums have taken similar steps to unravel the provenance of certain works in their possession since the Second World War. In January 2022, the Louvre announced a partnership with the auction house Sotheby's to support the Paris-based museum's action plan to research the provenance of items acquired between 1933 and 1945. Prior to this, the Louvre had signed partnerships with the French capital's Shoah Memorial and Hôtel Drouot auction house to verify the origin of works that entered its collection during this period.

In the United States, the government of the State of New York adopted, in August 2022, a law obliging local museums to display next to any works concerned, a label stating that these pieces were stolen by the Nazis during the Second World War. "We owe it to [Holocaust survivors], their families, and the six million Jews who perished in the Holocaust to honor their memories and ensure future generations understand the horrors of this era," said New York Governor, Kathy Hochul, in a statement at the time. But some experts say that few art institutions are currently implementing the new regulations, according to The Observer.

It is estimated that 600,000 works of art were stolen during the Second World War, of which some 100,000 are still missing.