A recent neuroimaging study has found that oxytocin administration decreases amygdala activity in individuals with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), bringing it closer to the levels observed in healthy individuals. The findings suggest that oxytocin might have the potential to mitigate heightened amygdala response to anger in individuals with ASPD.

The study was published in Neuropsychopharmacology.

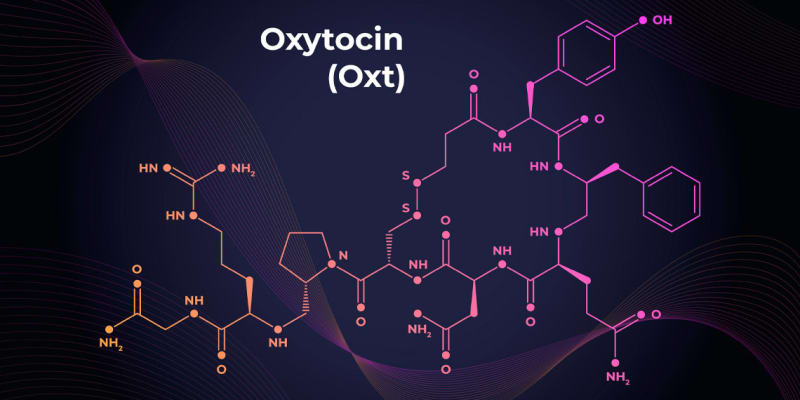

Oxytocin is a hormone and neuropeptide that is produced in the hypothalamus, a region of the brain. It plays a crucial role in various physiological and behavioral processes, including childbirth, breastfeeding, maternal-infant bonding, sexual activity, and emotional bonding between individuals. In recent years, oxytocin has also gained attention for its potential role in modulating social behaviors and emotions in individuals with various psychiatric disorders.

The new study aimed to investigate the effect of a single dose of intranasal oxytocin on amygdala reactivity to emotional facial expressions in individuals with ASPD compared to healthy control participants. The study employed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled within-subject design.

“Initially, we were interested in neurobiological processes underlying aggression in antisocial personality disorder,” said study author Haang Jeung-Maarse, an attending physician and postdoctoral researcher at Bielefeld University.

“Aggression is a hallmark of ASPD and can contribute to danger to others and one’s imprisonment. We targeted the amygdala as it is a brain structure that is in involved in emotion processing and wanted to test whether its function could be modulated by oxytocin.”

“Previous studies were mainly based on examining male study participants who were either children with behavioral problems or incarcerated individuals with psychopathy. There are hardly studies on women with ASPD. We aimed at uncovering similarities and differences in brain function between women and men with ASPD, as well as healthy women and men.”

The participants consisted of 20 men and 18 women diagnosed with ASPD, and 20 male and 20 female healthy control participants. The age range for all participants was 18 to 30 years. The ASPD participants were recruited from the Department of General Psychiatry at the University Hospital of Heidelberg, local probation services, and institutions offering anti-aggression trainings. The control participants were selected to match the age and IQ of the ASPD group.

The study involved two experimental assessments scheduled four weeks apart, during which functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was conducted to measure brain activity. In the fMRI task, participants were instructed to classify the facial emotion of various human faces as accurately and quickly as possible by pressing a corresponding button. The participants had to classify 72 briefly presented faces depicting angry, fearful, or happy expressions. The faces were presented in a randomized sequence, with an equal number of male and female faces for each expression.

The researchers found that individuals with ASPD exhibited faster responses to angry faces and showed different patterns of amygdala activation compared to healthy controls in the placebo condition. The administration of oxytocin seemed to modulate amygdala activation differently in individuals with ASPD and healthy controls. When individuals with ASPD were given oxytocin, the activity in their amygdala decreased.

In fact, the amygdala activity in individuals with ASPD who received oxytocin was similar to the activity observed in the amygdala of healthy individuals who received placebo. This suggests that oxytocin has the potential to reduce the heightened amygdala response to angry faces in individuals with ASPD.

“Oxytocin became known as ‘love hormone’ or ‘cuddle chemical’ because it is released during social bonding,” Jeung-Maarse told PsyPost. “It was first recognized for its role in mothers during the birth process and nursing. However, it can also affect individuals differently depending on their mental state and sex. We found that it decreased amygdala activity in response to angry faces in ASPD, whereas it did the opposite in healthy individuals. Also, we found a more profound effect in women.”

“Basically, we found a higher amygdala response to angry faces in ASPD. This contrasts findings in individuals with psychopathy, in which a lower amygdala activity in response to fearful faces have been reported (‘fear blindness’). Since psychopathy is discussed as a subtype of ASPD, our finding is surprising.”

The study included the largest sample of individuals with ASPD in the field of fMRI research, the researchers said. “I am still amazed that we were able to include complete data of 38 individuals with ASPD,” Jeung-Maarse remarked.

However, there were some limitations. The study did not include a clinical control group, meaning there was no group of individuals with a different clinical disorder for comparison. It is important to note that a significant portion of the ASPD sample in the study also met criteria for psychopathy. However, due to the small number of participants in the correlation analysis (only 9 out of 20 male ASPD participants and 7 out of 18 female ASPD participants), the researchers were cautious in drawing conclusions from these analyses.

ASPD is a recognized mental disorder characterized by a consistent disregard for the rights of others. People with ASPD often exhibit behaviors like deceitfulness, impulsivity, and a lack of empathy or remorse. Psychopathy, on the other hand, is a set of personality traits associated with antisocial behavior. It is not an official diagnosis but is evaluated using specialized tools like the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R). Not all individuals with ASPD are psychopaths, and not all psychopaths meet the criteria for an ASPD diagnosis.

“We did not include a clinical control group and we could not dissect between psychopathic and non-psychopathic individuals with ASPD,” Jeung-Maarse said. “It would be interesting to explore the subgroups of ASPD.”

The study, “Oxytocin effects on amygdala reactivity to angry faces in males and females with antisocial personality disorder“, was authored by Haang Jeung-Maarse, Mike M. Schmitgen, Ruth Schmitt, Katja Bertsch, and Sabine C. Herpertz.