Psilocybin has antidepressant-like effects and can improve cognitive function in a rat model of depression induced by chronic stress, according to new research published in Psychedelic Medicine. The findings provide new insights into the potential therapeutic applications of psychedelic substances and highlight the need for further research in this area to fully comprehend the underlying mechanisms.

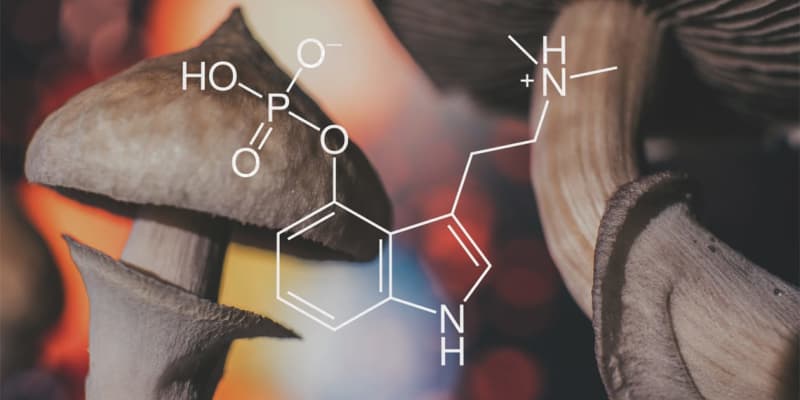

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain species of mushrooms, often referred to as “magic mushrooms” or “shrooms.” In recent years, there has been a growing interest in studying psilocybin and other psychedelics for their potential therapeutic effects. Psychedelics have shown promising rapid and persistent antidepressant effects in humans and animals. However, the exact mechanism behind these effects is not fully understood.

To investigate the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the antidepressant effects of psychedelics, the researchers used an appropriate animal model of depression. They chose a chronic stress-based model for greater translational value, as chronic stress is known to be a significant factor in depression. They specifically focused on female rats, as women are more susceptible to depression than men.

The researchers used a model called “adolescent chronic restraint stress” (aCRS) to induce depressive-like characteristics in female rats. This aCRS model uses mild developmental stress during adolescence, a period of rapid neurodevelopment and hormonal changes, to elicit depressive-like characteristics that persist into adulthood.

The study was designed to evaluate the effects of a single dose of psilocybin on depressive-like behavior and cognitive deficits induced by aCRS. The researchers used various behavioral tests to assess the rats’ responses, including the Forced Swim Test (FST) to measure passive coping strategies and the Object Pattern Separation (OPS) test to assess cognitive function.

The results showed that aCRS caused temporary weight gain reductions and long-term cognitive and behavioral deficits in the rats, resembling depressive characteristics. Rats subjected to aCRS displayed increased immobility in the FST, indicating a passive coping strategy, similar to depression in humans.

However, when the rats were given a single dose of psilocybin after the aCRS period, they showed improvements. Psilocybin-treated rats displayed enhanced cognitive function in the OPS test and reduced immobility in the FST, suggesting potential antidepressant-like effects.

The researchers investigated the brain regions involved in this process and found that the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus were important for the effects of psilocybin. They also looked at a gene called Grm2, which is related to neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to change and adapt). While they saw some changes in the expression of Grm2 after stress, psilocybin did not significantly reverse these changes.

The researchers suggested that the cognitive deficits caused by stress may be due to functional changes in the brain rather than major structural differences. They proposed that psilocybin might promote functional plasticity (changes in how brain cells communicate) rather than structural plasticity (changes in the physical connections between brain cells).

“A single dose of psilocybin produced long-lasting normalization of pattern separation and FST activities in aCRS rats, but without persistent increases in mRNA of a panel of genes relevant to synaptic density across several brain regions,” the researchers wrote. “Although there is considerable evidence that psychedelics initiate an acute period of synaptic plasticity, our results may indicate that functional plasticity, not structural plasticity, underlies the persistent antidepressant-like effects of psilocybin in our model. Our results seem to conflict with prevailing dogma and recent literature that suggest structural plasticity underlies this process.”

Despite these findings, the exact molecular mechanisms by which psilocybin exerts its antidepressant effects and cognitive enhancements remain unclear. Future research is needed to further explore and understand the cellular and molecular processes involved in these effects.

The study, “A Single Administration of Psilocybin Persistently Rescues Cognitive Deficits Caused by Adolescent Chronic Restraint Stress Without Long-Term Changes in Synaptic Protein Gene Expression in a Rat Experimental System with Translational Relevance to Depression“, was authored by Meghan Hibicke, Hannah M. Kramer, and Charles D. Nichols.