By Jack Barnett

Credit ratings agencies are probably best known among the general public for giving a clean bill of health to the world’s biggest banks before they collapsed in 2007/08, nearly sparking a global economic meltdown akin to the Great Depression.

Nonetheless, when they speak, financial traders listen.

Judgements published by the likes of Fitch, Moodys and S&P Global, the world’s foremost debt watchers, are taken as a rule of thumb in finance to assess whether a company, or a country, is likely to repay its debts.

Typically, the larger a company or country’s balance sheet, the less likely they are to default. That’s not to say that the big boys don’t face any default risks.

Late last night, Fitch said it is less confident the US – the world’s largest economy with a debt pile of over $30 trillion – will make good on its debts.

“The repeated debt-limit political standoffs and last-minute resolutions have eroded confidence in fiscal management,” the firm, referring to the annual wrangling between Republicans and Democrats over lifting the limit on how much the US is allowed to borrow, said in a report yesterday.

“The government lacks a medium-term fiscal framework,” Fitch said.

Under the current inefficient structure, US fiscal policy is heavily exposed to the whims of biased lawmakers motivated by political point scoring – the absolute worst position to be in.

Compounding this dynamic is “economic shocks as well as tax cuts and new spending initiatives” that are poised to push debt higher.

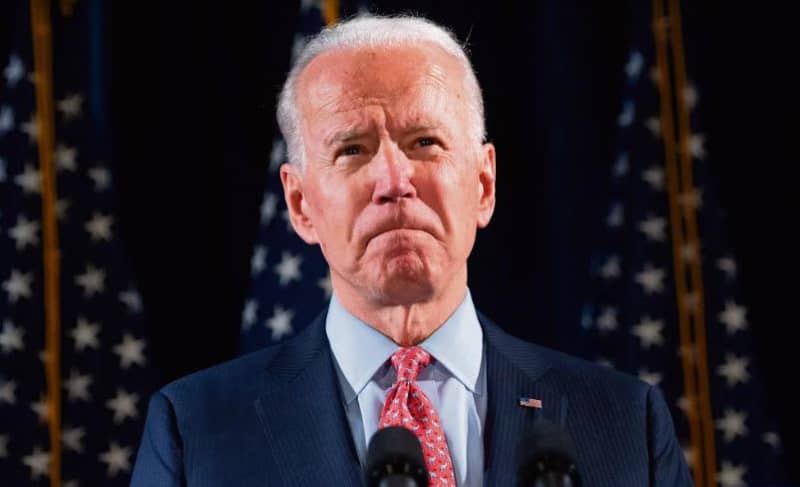

President Joe Biden’s “inflation reduction act,” while so far effective at drawing in investment to boost the US’s decarbonisation drive, will cost money. In fact, about $1 trillion.

Slowing growth too will wring out any spare capacity in the public finances. Fitch thinks the US will undergo a very short recession headed into 2024 and squeeze out just 0.5 per cent of additional output.

Still, the downgrade to AA+ from AAA doesn’t mean America is anywhere near defaulting.

Fitch, like its peers, employs a laddered system to score countries’ respective debt positions. The lower the rung, the greater the default risk.

America is now on the second highest rung, accompanied by Austria, Finland and New Zealand.

Fitch has assigned a credit rating of AA- to the UK. That rank was retained despite the firm last October downgrading its assessment of the country’s financial position to “negative” from “stable” in the wake of Liz Truss’s £45bn tax cutting mini-budget.

This is unlikely to be the last high profile credit downgrade. Economies are all grappling with the twin threats of high inflation, higher interest rates and poor growth.

Fulfilling debt obligations in such conditions is a lot tougher.