New research has uncovered distinct brain connectivity patterns in adolescents with two subtypes of callous-unemotional traits. The study found unique neurobiological features in these two variants, with conduct problems mediating the link between callousness and specific brain connections tied to socio-emotional processing. The findings have been published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Callous-unemotional traits are characterized by low levels of guilt, empathy, and concern for others. Children with these traits often exhibit deficient emotional responsiveness and interpersonal behaviors. These traits are similar to the affective and interpersonal deficits that are characteristic of psychopathy in adults.

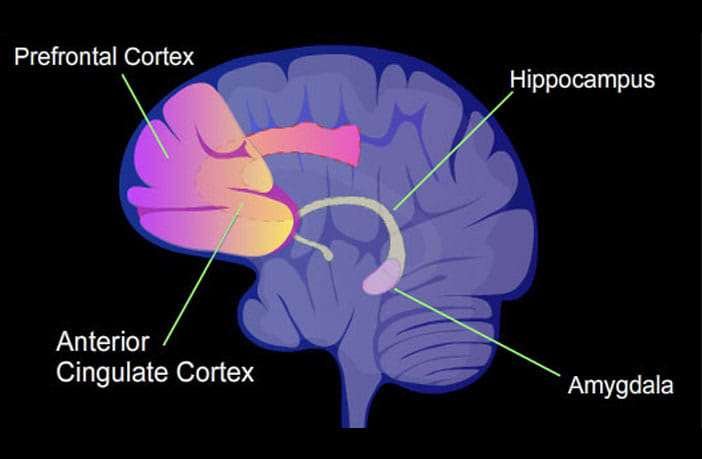

There are two primary subgroups of callous-unemotional traits: the primary variant (low anxiety) and the secondary variant (high anxiety). The researchers aimed to investigate the differences in brain connectivity patterns between adolescents exhibiting these two subgroups. Specifically, they were interested in exploring whether these variants of callous-unemotional traits are associated with distinct patterns of amygdala connectivity, a brain region that plays a significant role in emotional processing.

“The significance of this topic arises from the common assumption that children with high callous-unemotional traits constitute a uniform group mainly characterized by deficits in the activity of the amygdala,” said study author Jules Roger Dugré (@Jul_Dugre) of the University of Birmingham. “Nevertheless, extensive research spanning decades suggests that the severity of anxiety might underlie clinical subtypes among individuals with high callous-unemotional traits, namely those with (secondary variant) and without (primary variant) clinical levels of anxiety.”

The study involved data from 1,416 youth, which was gathered from the Healthy Brain Network initiative in the New York area. Data on callousness, anxiety, conduct problems, and negative life events were collected through parent-reported assessments. These participants also underwent functional neuroimaging scans.

By conducting a latent profile analysis, the researchers identified four distinct subgroups with varying levels of callousness and anxiety severity: Anxious (high anxiety, low callousness), typically developing (low anxiety, low callousness), primary variant of psychopathy (low anxiety, high callousness), and secondary variant of psychopathy (high anxiety, high callousness).

The primary variant was characterized by heightened connectivity between the left amygdala and the left thalamus (medial dorsal nucleus), potentially related to difficulties in adapting behaviors when reinforcement values change.

The secondary variant exhibited deficits in connectivity between the amygdala and various regions, including the posterior superior temporal sulcus/temporoparietal junction (pSTS/TPJ), postcentral gyrus (PoCG), and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), indicating more pronounced attentional impairments.

When comparing the primary and secondary variants, the researchers also uncovered both shared and distinct neurobiological features associated with their amygdala functional connectivity.

Both variants exhibited altered functional connectivity between the left amygdala and the right thalamus, indicating a common neurobiological trait compared to the typically developing group. But the primary and secondary variants demonstrated opposite functional connectivity between the amygdala and the left parahippocampal gyrus/fusiform gyrus (PHG/FF). The primary variant showed increased connectivity, while the secondary variant exhibited reduced connectivity.

Among adolescents who exhibited high levels of callousness, the severity of conduct problems seemed to act as a mediator between callousness and the functional connectivity between the amygdala and the dmPFC. In other words, conduct problems appeared to play a role in influencing the strength of the connection between these brain regions, which are known to be involved in socio-emotional processing and regulation.

“The key takeaway from this study is that children, with and without clinical levels of anxiety, exhibited variations in how the amygdala interacts with brain regions responsible for sensory and emotional memory processes,” Dugré told PsyPost. “Furthermore, our findings indicate that the extent of conduct problems (such as aggression and rule-breaking behaviors) played a mediating role in the relationship between callousness and the connection between the amygdala and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, which is commonly linked to the capacity for understanding mental states of others.”

“It is clear that further research should aim to replicate these findings using diverse samples, such as in young offenders,” Dugré said. “While the primary and secondary variants are subtypes that have received relatively robust validation, earlier studies have indicated that additional clinical attributes (like irritability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms) could also contribute to the significant heterogeneity within this population. Nonetheless, our study underscores the significance of examining the commonalities and differences of neurobiological substrates between distinct groups of children at risk for conduct problems.”

The study, “Altered functional connectivity of the amygdala across variants of callous-unemotional traits: A resting-state fMRI study in children and adolescents“, was authored by Jules R. Dugré and Stéphane Potvin.