By Eliot Wilson

The Labour leader will have his work cut out convincing voters in the countryside that he has their interests at heart, says Eliot Wilson

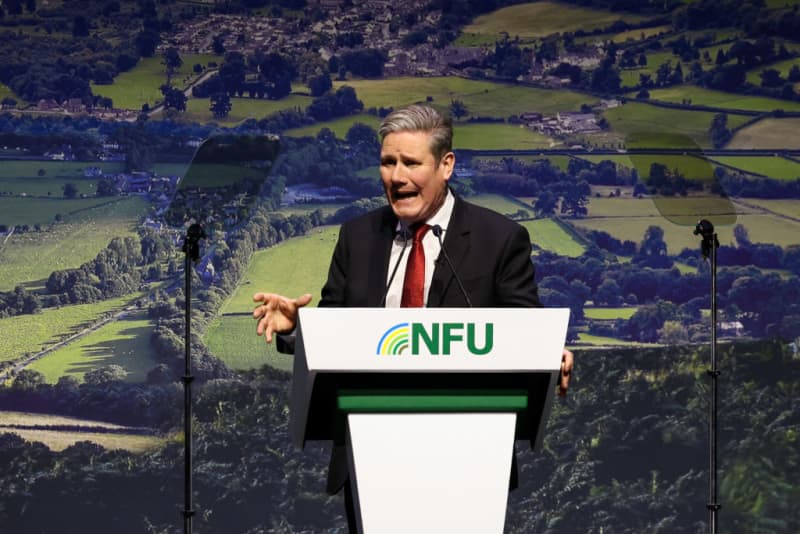

Keir Starmer’s first job was on a farm. This social media revelation will have taken many by surprise: the well-presented, five-a-side playing Sir Keir Starmer LLB BCL KC, human rights lawyer and hero of the McLibel trial, is almost the epitome of the urban, liberal, professional classes. Yet the Labour Party, which won just two of the UK’s 124 most rural constituencies at the last election, has begun a daring raid on the countryside.

Last week the National Farmers’ Union held its annual conference in Birmingham. The venerable institution, with over 300 branch offices and nearly 100,000 members, would once have been as welcoming to representatives of the Labour Party as a Capulet wedding to Montague gatecrashers. The union released polling data, however, which showed that 36 per cent of its members intended to vote Labour at the next election, while only 32 per cent would support the Conservatives. The Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, had a favourability rating of -36, while Starmer came in at -8.

Being slightly less unpopular than the main character is hardly a ringing endorsement – but it might represent an opportunity. Not only did Starmer seek out some cows to which he could stand close and look upon benevolently, he sent the shadow farming minister, Daniel Zeichner, to address the conference. The MP for Cambridge is a 67-year-old IT specialist who was handed the brief in 2020 after David Drew (Stroud) lost his seat, and he hammered home a counter-intuitive message that Labour would support farmers, and do so by slashing red tape.

Zeichner promised that an incoming Labour government would reduce “our reliance on insecure imports, supporting high quality, local produce for consumers and ending the shameful new reality of those empty supermarket shelves”. There would be a veterinary agreement to ease the delays at UK borders, and he savaged post-Brexit free trade deals for their potential damage to agriculture.

For her part, the outgoing NFU president, Minette Batters, challenged politicians of all parties. She identified food production as part of “our critical national infrastructure” and questioned why, on that basis, it was not guaranteed support from the public finances, and called for politicians “to treat food security as the same strategic priority as energy security”. And she had sharp words for the Prime Minister when he spoke warmly — or so he thought — of the farming community’s “love” for their livelihoods.

“Yes they love it,” she told a press conference, “otherwise they wouldn’t be doing it, but they are businesses and we need to have profitable agriculture… For too long, politicians have seen farming as a sort of cottage industry.”

If Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Party takes these messages to heart, it could be a huge change in policy towards agriculture and the rural environment. But it would also require fundamental philosophical change and hard choices, neither of which come naturally to the current leader. And it will also require voters in the countryside to accept that a metropolitan lawyer has their interests at heart.

Agriculture uses more than two-thirds of the UK’s land area, and we produce around 60 per cent of our domestic food supply. But the sector employs only one per cent of the workforce, and generates only half a percent of GDP. Using public money to support a small economic interest which has a wider strategic role and environmental commitments will never yield to simple answers.

Will the Labour Party take on these knotty questions? Can it afford to do so? Will MPs for urban and suburban areas accept that it is a nonsense to subsidise solar farms or the growing of maize for anaerobic digestion when protein crops and companion planting receive no such support? Will they and their constituents listen to the NFU president when she criticises “celebrities buying land and taking it out of production to greenwash other parts of their lifestyle”?

It is easy to see why Starmer looks at a political landscape in which Conservative support is collapsing and rates his chances, even in previously impenetrable strongholds. But he should remember that he is riding in the slipstream of a desperately unpopular government; as putative prime minister he is regarded sceptically, with almost half of those surveyed thinking he is doing badly. Reaching deep into the countryside might unbalance the fragile support he already has.