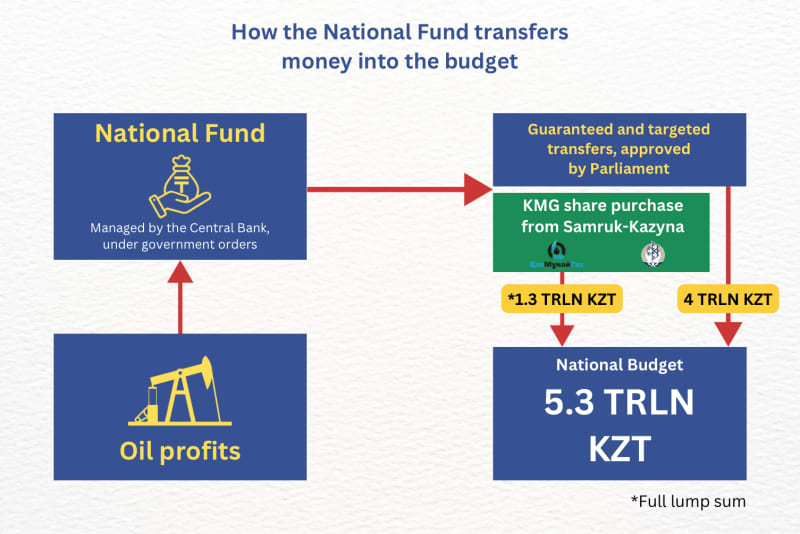

Illustration showing how the money gets transfered from the National Fund into the budget. Illustration by Daniyar Mussirov. Used with permission.

This article was written by Dmitriy Mazorenko for Vlast.kz. An edited version is published on Global Voices under a media partnership agreement.

Kazakhstan’s National Fund started in 2000 as a safety net for the government to be used in times of crisis. However, even during economically “good times” the government has continued to prop up its budget through withdrawals from it. This goes against President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s promise to impose greater financial discipline on the government by limiting such withdrawals. His ultimate goal is to double the assets of the fund by 2030, bringing them to USD 100 billion.

Simultaneously, the government was also tasked to launch a program of wealth redistribution through the newly established National Fund for Children and modernize strategic infrastructure with the Fund's money. Combined with these plans, the president’s leniency towards withdrawals to balance the budget shows how unlikely the objective of doubling the fund’s assets is under these circumstances.

Photo of Kassymkhan Kapparov. Used with permission.

Vlast spoke with the Dean of the School of Economics and Finance at AlmaU University, Kassymkhan Kapparov, about how the National Fund has changed in recent years. Kapparov, who also founded Ekonomist, an expert platform on Kazakhstan’s economics, answered questions regarding the control of the fund, its lack of transparency, and the contradictions in the plans for its use.

Dmitriy Mazorenko (DM): How was the National Fund created? What was the goal behind its creation?

Kassymkhan Kapparov (KK): The fund was created in 2000, after the existence of secret government accounts in a Swiss bank was revealed. In 2002, then-prime minister Imangali Tasmagambetov said the government had opened the accounts as a safety net. The parliament accepted this version and approved the creation of the f, through which the state was able to set aside earnings from growing oil prices.

In 1997, politician Galymzhan Zhakiyanov had touted the idea of creating a National Fund in an effort to avoid the overheating of Kazakhstan’s oil economy. It was supposed to become a full-fledged fund for future generations and serve as a macroeconomic stabilizer. It would have kept foreign currency liquidity away from the country’s market, thus preventing a sharp strengthening of the tenge exchange rate and, as a consequence, the so-called ‘Dutch Disease,’ through which the oil sector could kill the entire manufacturing industry.

Instead, the government essentially created its own reserve. As long as I have studied the fund, in the past decade, the issues concerning the fund have not been discussed transparently and, most importantly, these discussions have not influenced decision making.

DM: How is the National Fund used?

KK: For the past 24 years, the fund's assets have been annually transferred to the budget. This is what is called ‘guaranteed transfers,’ currently at a level around USD 8 billion. This essentially allows the government to live beyond its means. Transfers account for approximately 25 percent of the budget expenditures. The fund allows the maintenance of the current economic configuration, with a high level of state participation.

Should the government stop these transfers, it would need to undertake structural reforms and optimize work at government agencies and national companies. This could lead to social tensions. The fund is thus useful for political stabilization as well.

Besides guaranteed transfers, there are also targeted ones. The president sets out the strategy, and most of these transfers have been used in the past to resolve crises. When the banking system was collapsing in 2008, a targeted USD 10 billion transfer helped weather the storm.

Targeted transfers, however, are even less transparent. This money is allocated directly to specific tasks without oversight by the parliament. In the past five years, Tokayev has often repeated that Kazakhstan should move away from the practice of targeted transfers. This led to a less extensive use of this tool. But now that the government showed the need for additional cash injections, new ways of withdrawing National Fund assets came into place.

DM: The fund is thus not an independent institution, and it is managed by the president together with the government. Is there no public control over it?

KK: It is not even a legal entity. Nobody is directly employed by the fund. It’s an account held by the Ministry of Finance, which publishes a monthly balance of tenge-equivalent assets coming in and out of the fund.

The Central Bank is the manager of this account, responsible for the fund’s investment strategy. Its monthly report is in US dollars, which shows that the money stays out of the economy. The Central Bank manages the fund through a special department, which also manages gold and foreign exchange reserves. The fund's assets are invested through large international financial organizations.

Society is missing from this picture. The people have no control over the management of the fund. Its management council is almost entirely made up of officials and headed by the president, who always has the final word. The real manager of the fund was and remains the president.

Members of the parliament cannot regulate the fund or check its activities, with the exception of the transfers to the budget. Yet, even the portion of the fund's assets that get transferred to national companies cannot be scrutinized by the parliament. Some deputies tried, but the law prevents any further checks into national companies’ budgets.

DM: Why is transparency so important? Why is the National Fund so opaque?

KK: In terms of transparency, the National Fund of Kazakhstan is probably one of the most opaque sovereign funds in the world. Any information about its investment strategy and asset structure that is published on government websites lacks detail. The fund’s return on investment can also be considered opaque.

Transparency is key for investors because that is how they understand how stable the fund is. The lack of transparency is probably convenient for someone. The fund is a semi-secret reserve. When the public calls for transparency, their demands are met with a wall of silence.

Our current and previous presidents have only talked vaguely about the fund’s strategy for asset allocation. Deputies have been discouraged any further inquiry concerning this matter. Because the fund is, in essence, an instrument created by presidential decree, it can at any time be also disbanded by presidential decree.

DM: Does it follow that, without the National Fund, the current political regime would have been unsustainable?

KK: Yes, this entire massive architecture of presidential power would be impossible without the fund. Kazakhstan would not be a super-presidential country. We would have more transparency regarding the budget deficit, its structure would be visible, and all expenses would be accountable to the parliament. This would create space for public discussion.

If the president can close the budget deficit with just a signature on a decree, then there’s no point in debating. The Central Bank only acts as a performer of the president’s decisions. Now, the goal is for fund assets to reach a level of USD 100 billion. The Central Bank is not going to say no to this.

Written by Vlast.kz

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.