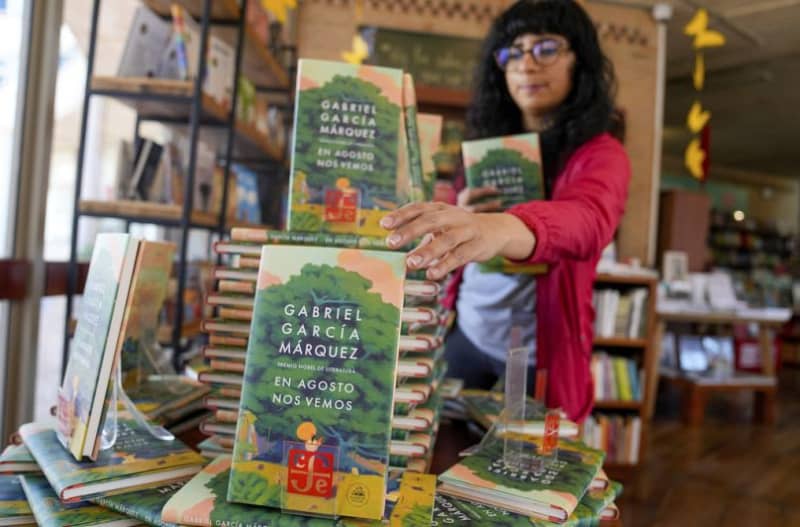

Gabriel García Márquez’s two sons disregarded their father's wishes not to publish his last work of fiction posthumously, but judging by the reaction to "Until August", they perhaps should have listened to him.

Reviews of the book, which was published ten years after García Márquez’s death in 2014, have veered from being barely kind to others which said it did have a few merits.

However, despite the generally bad press, this literary episode has raised the question of whether precious works of renowned writers should see the light of day, even against their wishes.

Is published and be damned always the best policy for the relatives left behind when the writer casts off this mortal coil?

"Until August" tells the story of a middle-aged woman who travels every year to visit her mother's grave and takes a new lover despite being happily married.

Justifying their decision to publish, García Márquez's son Gonzalo told the BBC that his father "wasn't in a position to judge his work as he could only see the flaws but not the interesting things that were there".

Mixed reception

García Márquez was suffering from senile dementia before his death at the age of 87 in Mexico City.

Gonzalo said he didn't "find it as disastrous as Gabo had judged it" and that it was a valuable addition to his work because it showed a new side to him and was "unique".

Many critics have not been so generous.

The New York Times sniffed that the book by the late Colombian master and Nobel laureate was a disappointment.

“It would be hard to imagine a more unsatisfying goodbye from the author of One Hundred Years of Solitude,” wrote Michael Greenberg.

"One Hundred Years of Solitude" is the 1967 novel which introduced the world to Latin American literature.

In contrast, García Márquez’s last offering is “hardly sufficient for it to be called a novella, much less a finished novel”, wrote Greenburg.

In Spain, where García Marquez spent some formative years when he lived in Barcelona in the 1970s, critics were a little bit more kind.

Nadal Suau, writing in El País newspaper, wrote: "It has virtues but it is not advisable to be deceived about its true dimensions: they are small." This appears to be another way of saying the book has few merits.

However, in Britain the Daily Telegraph's Sarah Perry was more charitable.

"It's as if the book contained both Marquez the elder and Marquez the younger, with the perception and weary good humour of old age conveyed in the searching, tentative manner of the apprentice," she wrote.

Disobeying wishes?

Like García Márquez, a succession of literary greats have ordered some of their works should be destroyed before their deaths.

However, when their relatives disobeyed it was sometimes to the benefit of the wider world.

Before author Franz Kafka died from tuberculosis in 1924, he told friend Max Brod to burn all of his works.

Disregarding his friend's wishes, Brod later published his collection of works including "The Trial", "The Castle" and "Amerika".

"The Trial" is widely acknowledged as a classic, depicting the struggle of the individual against the powerful state.

According to legend, Roman poet Virgil asked for the scrolls on which he wrote his epic "The Aeneid" to be burned because he feared he would be unable to finish the work before his death.

The epic poem is a criticism of Western civilisation and its worst traits like violence, chauvinism and imperial yearning. It is still regarded a classic.

Vladimir Nabokov, the writer of "Lolita", asked his wife to destroy his final novel, "The Original of Laura", if he did not live to complete it.

In 2009, thirty years after Nabokov's death, his son released the unfinished work, which had been written in pencil on index cards.

These episodes prove, perhaps, that the death-bed wishes of great writers are not always to be obeyed.

What would the world be without these works of Kaka and Virgil?

It perhaps raises a wider question which goes beyond literary greats. How often do us mere mortals decide to ignore the death bed wishes of our loved ones?

This is hard to know but one thing which is interesting is why we might do this? It was suggested that García Márquez's two sons might have chosen to publish "Until August" out of love for their father, perhaps considering that the book was better than it really was.

Of course, the cloud of grief often obscures good judgement about why our relatives expressly ordered that they did or did not want something to happen.