By Hans Nicholas Jong

JAKARTA — Deforestation for oil palm plantations continues unabated at the northern tip of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, likely driven by new processing mills that in turn may ultimately be supplying major consumer goods companies.

Plantation-driven forest loss has for decades eaten away at the Leuser Ecosystem, home to critically endangered Sumatran orangutans, tigers, rhinos and elephants. The Leuser landscape spans 2.6 million hectares (6.4 million acres), much of it in the province of Aceh. But while past deforestation was carried out by a handful of large operators carving out chunks of the forest at a time, today it’s smaller operators administering “death by a thousand cuts” to feed a growing number of processing mills, according to monitoring by U.S.-based campaign group Rainforest Action Network (RAN).

RAN’s latest investigation found at least 192 hectares (475 acres) of forests were cleared in one concession alone in Aceh Tamiang district, Aceh province, in 2023. The concession, reportedly owned by a retired public servant named Bukhary, is located within the borders of Gunung Leuser National Park, one of Southeast Asia’s last great swaths of intact rainforest.

The national park is a formally protected area at the heart of the Leuser Ecosystem and is part of the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra (TRHS), a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2004 and placed on UNESCO’s danger list since 2011.

According to RAN’s investigation, forest clearing inside the concession started in 2021, after Bukhary erected a sign claiming owner of 1,100 hectares (2,718 acres) of land inside the national park. Between March 2021 and April 2022, 60 hectares (148 acres) of forest were cleared in the concession.

An excavator operating at Mr. Jumady’s palm oil concession inside the Gunung Leuser National Park, near Tenggulun village, Aceh Tamiang, Indonesia, in August 2023. Image courtesy of RAN.

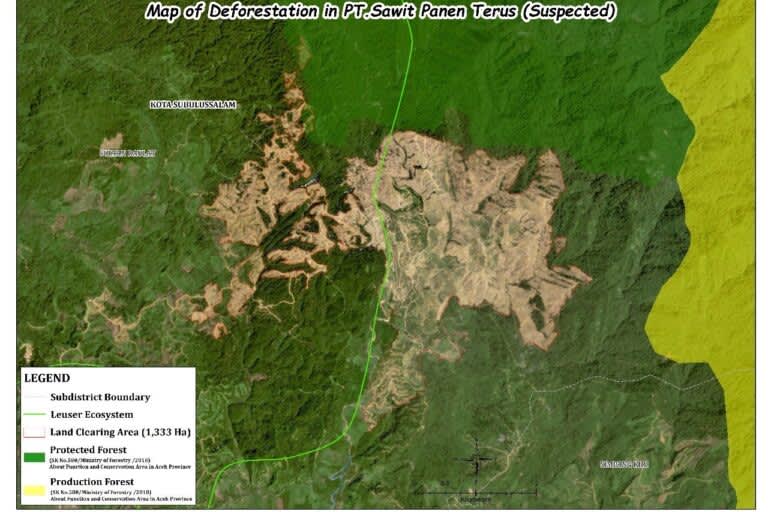

Another concession, this one at the northern tip of Gunung Leuser National Park, also underwent a deforestation spree in 2023, with 1,333 hectares (3,294 acres) cleared, or an area four times the size of New York City’s Central Park. That concession is held by a company named PT Sawit Panen Terus (SPT), which RAN described as “a new rogue actor” that has sped up its rate of clearing in the last six months.

RAN said the deforestation is especially alarming because it’s happening in a region of the Leuser Ecosystem called the Singkil-Bengkung Trumon peat swamp, described as one of the most ecologically rich and vulnerable parts of the ecosystem.

‘Death by a thousand cuts’

RAN said the deforestation in Leuser is a part of a wider trend across Indonesia of plantation-linked forest clearing increasing after years of reported declines.

Satellite monitoring by technology consultancy TheTreeMap shows that deforestation by the palm oil industry in Indonesia increased in 2023 for the second year in a row, bucking a decade of gradual decline.

Unlike palm oil deforestation in the past, which carried out by a smaller number of actors but on a larger scale, the recent forest loss is occurring at a smaller scale but by a larger number of operators. And even if individual concessions aren’t clearing thousands of hectares at a time, as was once the case, the current trend is still deeply concerning as it portends a “death by a thousand cuts” for the last remaining lowland forests of the Leuser Ecosystem, RAN said.

It added that this deforestation is being driven by local elites rather than small farmers, as evidenced by the use of expensive machinery and the ability to acquire permits within protected areas like Gunung Leuser National Park. These elites “have the resources and influence needed to get away with deforestation and plantation establishment within protected areas,” RAN said.

Bulldozers are being used by palm oil plantation PT Sawit Panen Terus to destroy significant areas of lowland rainforest in the Leuser Ecosystem, in February 2024. Image courtesy of RAN.

Supply chain risk

There’s also a risk that palm oil produced from this deforestation land could ultimately end up in household name products ranging from Colgate toothpaste to Oreo cookies to Lays potato chips, RAN’s investigation suggested.

This is because suppliers to these brands are known to source their palm oil from mills near and around the Leuser Ecosystem. Those mills, in turn, are the closest processing facilities for the deforesting plantations, which have to sell their palm fruit to the nearest mills as the fruit goes bad 48 hours after harvest.

RAN’s investigation identified a number of these mills and the major brands that could be exposed to dirty palm oil if they’re ultimately getting their palm oil from these mills.

The mills closest to Bukhary’s plantation sell their product to major palm oil traders like Apical (part of the Royal Golden Eagle Group), Musim Mas, Golden-Agri Resources (GAR) and Wilmar, according to RAN. These traders, in turn, are the main suppliers to multinationals like Procter & Gamble, Mondelēz, Colgate-Palmolive, Nissin Foods, Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever.

The mills near SPT, meanwhile, include PT Samudera Sawit Nabati and PT Global Sawit Semesta, both of which have previously been exposed by RAN for driving deforestation in the area.

Unilever has banned these two mills from its supply chain and announced the decision on its list of suspended suppliers.

Map showing the indicative area of palm oil company PT Sawit Panen Terus’s clearing of lowland rainforests for a new palm oil plantation in Subulussalam, Aceh, Indonesia, in February 2024. The map shows parts of the lowland rainforest that have been cleared and are located within the boundary of the Leuser Ecosystem (shown by green line). Image courtesy of RAN.

New mill, who dis?

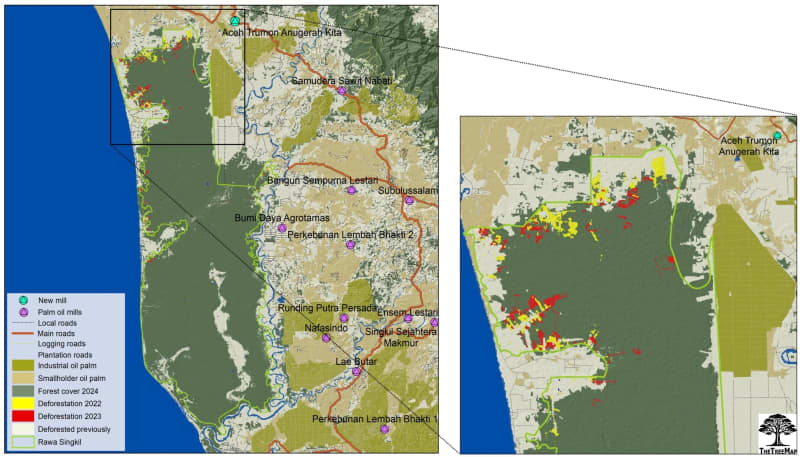

A new mill, PT Aceh Trumon Anugerah Kita (ATAK), has recently been built in the area, just outside the northeastern boundary of Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve, a part of the Leuser Ecosystem. The reserve has been described as the “orangutan capital of the world” because it’s home to the densest population of Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii) anywhere on the island: 1,500 recorded individuals, or 10% of the species’ total population.

Since the new ATAK mill started operating in 2022, there’s been an increase in deforestation within the reserve. Using satellite imagery from forest monitoring platform Nusantara Atlas, RAN found the rate of destruction within the wildlife reserve in 2023 was greater than at any time in the past decade, with clearing of peat forests and construction of canals to drain the carbon-rich peat soil.

This indicates that the new mill might be driving the demand for illegal oil palm plantations across the region, said Gemma Tillack, RAN’s forest policy director.

“There seems to be a correlation between increase in crude palm oil mill capacity and creation of clearing and land speculation,” she told Mongabay. “We can’t prove that, but from our observation, you create a new market and actors are responding [by establishing new plantations].”

Map showing the location of the PT Aceh Trumon Anugerah Kita (ATAK) mill just outside the north-eastern boundary of the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve in Aceh Selatan, Indonesia. The map also shows the uptick in deforestation within the reserve after the new mill became operational in 2022 and 2023. Map provided by TheTreeMap/Nusantara Atlas.

Tillack said the ATAK mill doesn’t seem to have any arrangements with its clients to ensure it’s not buying palm fruit from deforesting plantations. RAN said it contacted major traders like Musim Mas, GAR and Apical, all of which said they’re not sourcing from ATAK and haven’t begun engagement with the mill to educate it on their no-deforestation requirements.

But at least one trader and refinery operator — Permata Hijau Group, one of the top 10 palm oil processors and traders in Indonesia — is buying from ATAK. Permata Hijau’s suppliers’ lists show that its PT Permata Hijau Palm Oleo refinery, in neighboring North Sumatra province, sourced from ATAK in 2023.

Permata Hijau hasn’t responded to Mongabay’s inquiry as of the publication of this story.

Permata Hijau has previously been exposed for sourcing from PT Kallista Alam (KA), a company blacklisted by other major traders due to its violation of “no deforestation, no peatland and no exploitation” (NDPE) policies.

In 2012, fires that began on KA’s concession razed 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres) of pristine lowland rainforest in the Tripa peat swamp, part of the Leuser Ecosystem. The company was found liable for the fires, and in 2015 the Supreme Court ordered it to pay a then-unprecedented 366 billion rupiah (about $26.5 million at the time) in fines and damages.

Permata Hijau said it bought palm oil from KA in the second half of 2019 because of a lapse in its mill disclosure process. Nevertheless, the palm oil from KA found its way into the global supply chain, since Permata Hijau sells to commodities giant Cargill.

Cargill, in turn, supplies multinationals like Nestlé and Mars. Permata Hijau, which adopted an NDPE policy in 2017, said it has ceased all sourcing from KA as of June 2020.

But because Permata Hijau now sources from ATAK, there’s a possibility the company’s supply chain is once again tainted, Tillack said.

“We profiled that Permata Hijau is a refinery that has been willing to accept palm oil from dirty plantations,” she said. “This means that global brands that are sourcing from Permata Hijau like Cargill may be sourcing from palm oil from deforestation.”

RAN also highlighted another mill currently under construction, PT Aceh Bakongan Eka Nabati (ABEN), located on the edge of the Kluet peat swamp, one of the three remaining coastal peat swamps in Leuser. (The other two are Tripa and Singkil-Trumon.) The Kluet peat swamp is zoned as a forest protected area.

“So the new mill is constructed very close to the boundary of protected peatland,” Tillack said.

The groundbreaking for the ABEN mill took place in August 2023, with the local district head in attendance. The mill is expected to cost 120 billion ($7.7 million) and when fully operational is projected to process up to 35 metric tons per hour of palm oil.

To ensure the financial viability of a new mill, the companies that build them typically require that there’s an oil palm plantation nearby of at least 5,000 hectares (12,400 acres) to provide a sufficient supply of palm fruit, according to an analysis by conservation biologist Timothy J. Killeen.

That means both of the new mills in the Leuser Ecosystem, ATAK and ABEN, are likely to drive the establishment of new plantations, Tillack said.

Piles of palm oil fresh fruit bunches that have been delivered by brokers to PT Aceh Trumon Anugerah Kita (ATAK) in Aceh Selatan, Indonesia. Image courtesy of RAN.

Greater investment in protection, transparency

To ensure consumers aren’t buying products associated with deforestation and the loss of critical habitat for species like orangutans, multinationals and suppliers like those identified in RAN’s investigation must put these mills on their no-buy lists, RAN said.

“The global market now demands palm oil that is free of deforestation, peatland development, and exploitation of communities and workers, especially in global biodiversity hotspots like the Leuser Ecosystem,” RAN said.

It’s also important for these companies to increase their investments in programs to protect the Leuser Ecosystem from further destruction, RAN said.

Some companies and governments have made commitments to that end. At the annual conference of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) in November 2023, the Aceh provincial government launched a road map aimed at preventing deforestation and supporting smallholders in accessing the international market for sustainable palm oil.

Sustainable initiatives have also started in several districts in Aceh, like Aceh Tamiang, where companies like Unilever, PepsiCo, Mars and Mondelēz are supporting landscape and jurisdictional approaches to sustainable palm oil, which entails collaborative forest monitoring systems to identify and respond to deforestation.

But the ongoing deforestation and expansion of plantations in parts of the Leuser Ecosystem shows these investments and efforts toward traceability and compliance aren’t enough, RAN said.

This was also reflected in a 2023 report by RAN, which evaluated the performance of 10 of the world’s biggest consumer goods companies — Colgate-Palmolive, Ferrero, Kao, Mars, Mondelēz, Nestlé, Nissin Foods, PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever — on sustainable practices, like NDPE policies, supply chain transparency and forest monitoring systems.

The 2023 assessment found that none of the 10 brands have taken adequate steps to address their contribution to deforestation and human rights violations in forest-risk commodity supply chains, with companies like Nestlé and Mars failing to provide independent verification of their claims of having nearly or completely deforestation-free supply chains.

With new mills and plantation expansion continuing to threaten the Leuser Ecosystem, companies should work together with governments and communities to invest in lasting solutions that support the protection and restoration of the ecosystem, RAN said.

“Collaborative forest and peatland monitoring and response systems must be established that can enforce their policies throughout supply chains all the way to the forest floor in the Leuser Ecosystem,” RAN said. “The systems that are in place are clearly failing to halt new deforestation for palm oil.”

Banner image: Sumatran orangutan in the Leuser Ecosystem, Aceh, Indonesia. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay