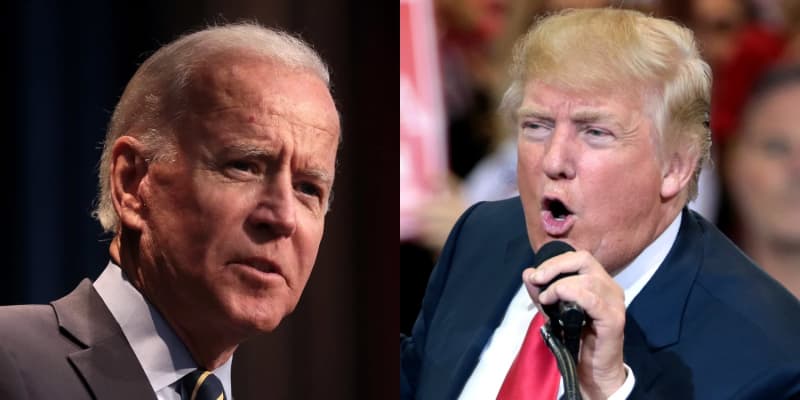

In a recent study, researchers dove into the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election’s polarized waters to explore how such an environment influences individuals to morph their political stances into deep-seated moral beliefs. Their findings, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, indicate that increased perceptions of societal polarization and negative encounters with opposing political expressions significantly heightened individuals’ moral convictions on key issues.

The research provides important insights into attitude moralization, the psychological process through which an individual’s stance on a specific issue becomes tightly interwoven with their core moral beliefs and convictions.

“Much of the existing research has suggested that the moralization of political attitudes at a large scale can be dangerous for society and democracy. For example, moralization tends to make people more opposed against compromises, more hostile towards people with different perspectives, and more willing to reject the rule of law,” said study author Chantal D’Amore, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

“This is what made us very interested in a different question that is not well understood yet: what is it that makes people moralize their political attitudes in the first place? We reasoned that if we understand how attitude moralization occurs specifically within polarized contexts, this can help in explaining how otherwise constructive discussion between groups spirals out of control and becomes a threat to healthy democratic functioning – such as observed in the 2020 U.S. election and its aftermath.”

The study was conducted over four months, covering a crucial period of the U.S. 2020 election campaign. The four-wave longitudinal design included the following time points: one month before the election, right before election day, one month after the election, and immediately following the inauguration day and the Capitol Hill riot.

The study’s participant pool consisted of U.S. residents who supported either Biden or Trump in the 2020 presidential election. In total, the study started with 1,075 participants at the first wave, which, after accounting for dropouts and exclusions based on criteria such as duplicate responses or nonsensical answers, was refined to 931 participants for analysis. The participants were then followed across four waves of data collection, with the final sample sizes for analysis being 355 Biden supporters and 186 Trump supporters.

To assess moral convictions associated with political attitudes, participants rated their agreement with statements tailored to assess how strongly they believed their position on key issues (like mask mandates, climate policies, and Supreme Court appointments) reflected their core moral beliefs.

To assess perceived societal polarization, the participants were asked the degree to which they agreed with various statements about division and opposition between political groups within society. For example: “Biden supporters and Trump supporters are in direct opposition of each other with regard to their views on relevant political topics.”

To capture the political homogeneity of participants’ social networks, participants were asked to list people in their network with whom they had discussed political or societal topics. They then rated the political orientation of these individuals towards Trump or Biden. This measure allowed the researchers to quantify the political uniformity of participants’ immediate social circles.

Participants were also presented with recent statements or actions from the political outgroup that were likely to be perceived as controversial or harmful. These outgroup expressions were chosen based on their relevance to the election and potential to elicit strong emotional responses. The participants then rated their perceptions of dyadic harm (the sense that the outgroup intended to cause harm or suffering) and their emotional responses (anger, contempt, and disgust) regarding the presented content.

The researchers found that both perceived dyadic harm and emotional responses played significant roles as within-person drivers of moralization. Specifically, when participants perceived an increase in intentional harm or malice from the political outgroup and experienced heightened negative moral emotions in response to outgroup expressions over time, they were more likely to strengthen their moral convictions regarding political issues.

Perceived polarization played a crucial role in facilitating the moralization of attitudes. Increases in perceived societal polarization and political homogeneity within participants’ social networks were found to predict increases in both perceived dyadic harm and negative moral emotions over time.

Importantly, the findings were consistent across supporters of both major political candidates, suggesting that the mechanisms driving the moralization of attitudes are not unique to one political ideology or affiliation.

“Like in our previous research, we found that the actions of political opponents can trigger people to moralize their attitudes when they seem intentionally harmful and induce strong emotional responses like anger — which defensively pushes individuals’ attitudes into the moral domain,” D’Amore told PsyPost. “What is new about this study, is the discovery that the perception of polarization between the political groups really matters to start with.”

“Specifically, perceiving politics in terms of a structural division between ‘us’ and ‘them’ appears to make people prone to moralize their attitudes to protect their core values in society against their opponents. Put differently, when our political opponents seem to threaten what we value in society, we emotionally protect our values by moralizing our attitudes on the topics that are central to the political discourse at that time.”

The findings suggest a dynamic relationship between perceived polarization and attitude moralization. Not only do increases in perceived polarization predict stronger moral convictions over time, but these strengthened moral convictions, in turn, might contribute to heightened perceptions of polarization.

“Although we designed this study to answer questions about the process of moralization, additional findings of this study suggested that attitude moralization, in turn, makes people perceive even more polarization later in time,” D’Amore explained. “This seems concerning because it suggests that there may be a mutually reinforcing cycle between perceived polarization and moralization that could spiral out of control and eventually put the democratic system at stake.”

“However, this is an exploratory finding that should be interpreted with caution and should be formally tested in future research. For example, the data suggested that on average, polarization and moralization may strengthen but also weaken at specific moments in time, such as after the election – and we suspect that to predict the future of polarizing societies, we need to be able to explain both escalation and de-escalation patterns in society at large.”

The study, “How Perceived Polarization Predicts Attitude Moralization (and Vice Versa): A Four-Wave Longitudinal Study During the 2020 U.S. Election,” was authored by Chantal D’Amore, Martijn van Zomeren, and Namkje Koudenburg.