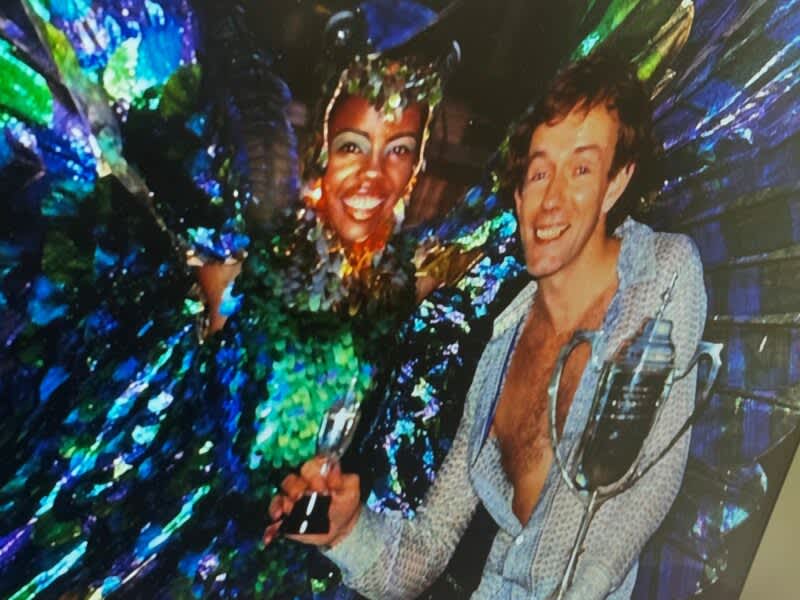

Masquerader Sherry-Ann Guy (L) and Carnival designer Peter Minshall (R) with some of the trophies honouring the costume ‘From the Land of the Hummingbird,’ one of his presentations for the Trinidad and Tobago 1974 Carnival season. Capture of existing archival photo by Janine Mendes-Franco, used with permission.

Fifty years ago, during Trinidad and Tobago's 1974 Carnival season, designer Peter Minshall forever changed the collective sensibility regarding what was possible with masquerade. It wasn't that the stage at the Queen's Park Savannah — the mecca of the Carnival experience in the heart of Port of Spain — hadn't seen splendour before. The golden era of Trinidad Carnival in the 1950s and '60s saw “mas men” like George Bailey and Harold Saldenah bring historical portrayals to life with great pomp and circumstance, while designers like Geraldo Vieira prided themselves on pushing creative boundaries through pyrotechnics and feats of engineering. Yet, there was something different about Minshall's “From the Land of the Hummingbird.”

To begin with, it was a child's costume, made for his adopted sister Sherry-Ann Guy to compete in Kiddies Carnival that year. Meant to depict a hummingbird in flight, it was mesmerising in its simplicity, and stunningly effective on stage as either the sun or the stage lights caught the portrayal's iridescent wings while the masquerader danced. So game-changing was the costume that, among other prizes and accolades, it won the coveted Junior Carnival Queen and overall Individual of the Year titles, catapulting Minshall into the limelight and laying down the sturdy foundation of what would be an outstanding career in mas-making.

Prior to his involvement in Carnival, Minshall had primarily been working in London as a theatre designer. After “From the Land of the Hummingbird,” however, his artistic consciousness became intimately aligned with Trinidad's annual sacred ritual. That unique lens through which he saw everything allowed Minshall to build a career as an artist whose work has been seen on some of the world’s biggest stages: three Olympic Games, two World Cups (one cricket, one football), collaborating with Jean-Michel Jarre on two of the largest open-air concerts in recorded history and, perhaps most beloved of all, his contributions to Carnival.

A view of the Queen's Park Savannah, where Minshall's mas was performed and participated in by both masquerader and spectator, from Killarney, where the ‘From the Land of the Hummingbird’ exhibit was staged. Photo by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

To commemorate the impact of both the costume and its creator, a free public exhibition was launched at Killarney — a heritage castle on the western side of the Queen's Park Savannah — to mark “From the Land of the Hummingbird”‘s 50th anniversary.

To create the costume — though to Minshall, it was first and foremost a work of art — it took him and his 12-person team five weeks to get it right, giving Guy the mobility she needed to really “play the mas” and make the creature come alive.

The exhibit, curated by Kathryn Chan, who worked closely with Minshall from about 1987, opened on January 23. It allows visitors to get an up-close-and-personal look at everything from the designer's early working drawings to the only known surviving film footage of his 1974 presentation.

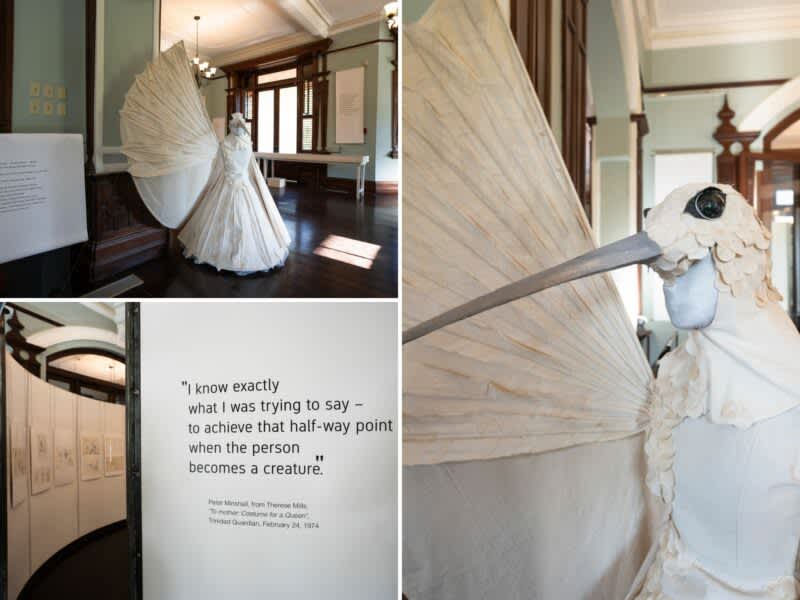

The commissioned model of the costume's scale and structure at the exhibit. Photos by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

It also included a specially commissioned, expertly tailored model of the costume's scale and structure, a selection of Minshall's drawings for the formative work “From the Bat to the Dancing Mobile,” and photographs and artefacts from the artist's extensive private archive. In an effort to continue to gather further documentation on the mas, patrons and Carnival enthusiasts were also invited to share their own stories and photos with the curators and archivists.

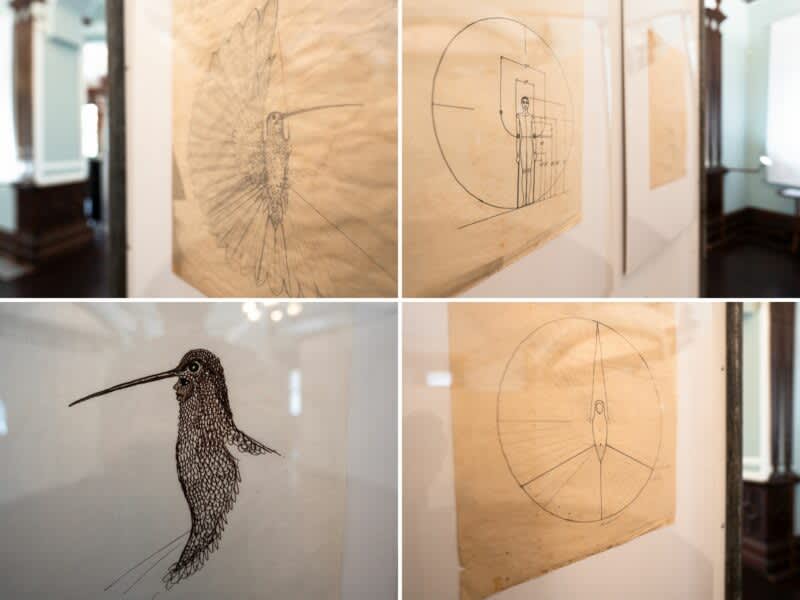

Via email and phone, I interviewed Chan about the exhibit and the impact and legacy of Minshall's work. Her curatorial starting point was to offer some insight into Minshall's process — the sheer number of drawings and sketches he does in order to bring his ideas to fruition. “These sixty-five working drawings for the hummingbird,” Chan says, “done early in his career, are a neat sample to explain thoughts to people like me, who take the work from drawing, through making, to life. I wanted to share the layers of thought of the artist alone in his studio. Looking closely, you will see that he thinks through construction, shape, materials decoration, references and technical drawings.”

Some of Minshall's sketches and technical drawings at the exhibit. Photos by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

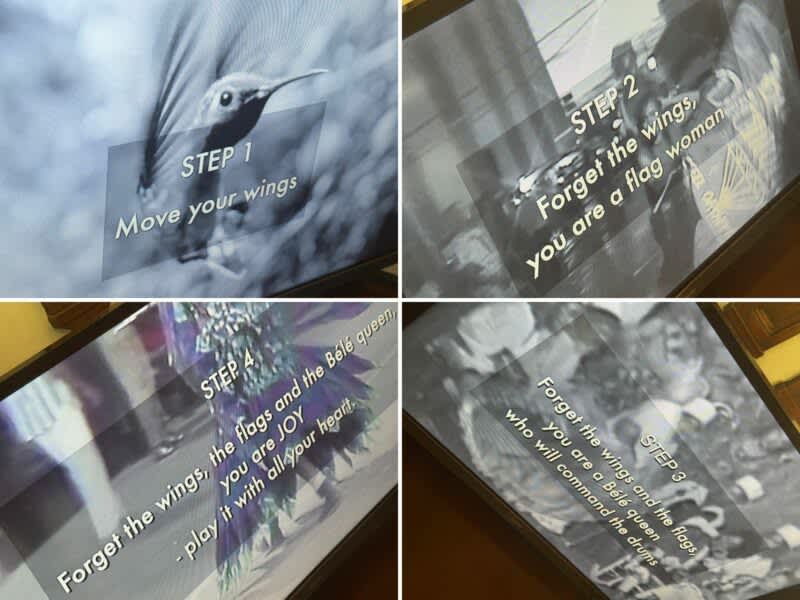

The journey of curating the exhibition was a learning process for her — at least in terms of discovering new things about Minshall. “For the hummingbird,” Chan explains, “one fundamental aspect that revealed itself as most important to him is that he wanted the mas to communicate joy.” Individual elements that go into a costume, she says, like the full skirt of a Bélé dancer, the flags skilfully wielded by the flag woman of steelpan culture, or the wings of the bird in nature, simply inform the work or help to communicate an idea: “They are not the essence of what he was getting at. The essence is JOY. And an understanding that through this art form, he can instantly convey a message to an audience. This is art.”

A Minshall quote explaining his ‘dancing mobile’ concept, displayed at the exhibit. Photo by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

As much as it is art, it is also math. For the hummingbird — as for much of his other work — Minshall used simple geometric forms and clean, basic lines to create intricate movement. I asked Chan if that was the secret of his genius. “Geometry,” she said, “is always involved” when it comes to Minshall's designs. As shown in his technical drawings, the skirt and the wings of the hummingbird are two separate 360-degree circles with radiating lines. Measurements are also critical: the relationship of the form to the human body, the width of the fabric. To this end, Chan cites the 7 x 7-foot (2 x 2-metre) cloths of Minshall's 1990 Carnival band “Tantana,” as well as the scale of a form to the performer, as with that band's mesmerising queen and king, Tan Tan and Saga Boy.

“The wind puppets that now pollute our environment in front of shops worldwide do not dance,” Chan quips. “They flop around. Many would not know that in the original incarnation, designed for the athlete's stadium party at the closing ceremony of the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, Minshall's technical drawings for the legs have a specific angle that allows the wind to travel up and out to the arms of those wind puppets. The angle of the legs causes the puppets to dance correctly. Two fans push the wind through each leg, articulating the legs and arms. It is geometry. This is his genius.”

Bat mas being shown on a screen at the ‘From the Land of the Hummingbird’ exhibition. Photo by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

Chan thinks Minshall's design for the human body is the most critical aspect of his work. “For the hummingbird, Minsh is studying the spine of the human being to see how a human figure will move the form he is designing.” It all harkens back to the bat: “This ingenious form of traditional mas is attached to the feet, the periphery of the body, and the arms,” Chan explains. This archetype is the basis for most of the technology behind Minshall's forms. “Tan Tan and Saga Boy also owe their origins to the bat, she continues: “The entire form vibrates when the performer moves [his/her] feet and arms. The movement starts at the gut and moves out to the furthest tip of any form. This is also his genius.”

It's a genius that has consistently connected with people, demonstrated so well by the hummingbird costume. “The presentation hit a nerve,” Chan believes. “It made people feel that joy. It stunned [them]. The craftsmanship of the mas is at the core of conveying that feeling.” She recalls Minshall being detail-oriented and very particular about the materials used — “the thickness of a hand-painted line of varnish, the hand-sewing of elements, and the structure of the cancan to define a pyramid-like skirt shape in contrast to the wings that would flutter.”

Screen captures of Minshall's instructions to masquerader Sherry-Ann Guy that were featured in a film at the exhibit. Images by Janine Mendes-Franco, used with permission.

But it didn't end there. Drawing on his theatrical training, Minshall rehearsed the performance with Sherry-Ann Guy “every day for five weeks until she absorbed the essence of what he wanted,” giving her all the tools to successfully play the mas and have fun while doing it. “Every photograph of her is a testament to this,” Chan notes. “According to one visitor who saw her in 1974 and who visited the exhibition, ‘She became the mas and the mas became her.’ In other words, the hummingbird and the child became one.”

Just as integral to Minshall's designs was the social commentary behind them. Taking a cue from the calypso tradition, his presentations always had something to say — to the point, Chan explains, where you could study “so many issues and aspects of humanity through his work.” When she first met him, he was working on “Jumbie” in 1987: “He made a contemporary minimalist form out of cardboard, staples and paint, but it echoed an oil derrick. The forms were a commentary on how oil had “jumbied” or ruined us. That oil money came along and bazodeed the people. The presence of the oil money suddenly diminished the human and natural aspects of our environment.”

Mas man Peter Minshall, speaking on camera as part of a film that was shown at the ‘From the Land of the Hummingbird’ exhibition. Photo by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

Universal themes, told from a regional perspective. “Coming from the Caribbean,” Chan says, Minshall's “unique task was to define his artistic medium” — one that was “in tune with his environment and culture. He knew somewhere along the line that it was not to be a classical painting or a traditional sculpture that was, to him, distant.” Instead, he was influenced by his childhood experiences of “exploring folk art, Carnival culture, and the rich biodiversity of the islands of Trinidad and Tobago.”

Contemporary Trinidadian artist Christopher Cozier, believed to be the first living, Anglophone Caribbean-based creative whose work has been shown at MoMA, once suggested that Minshall's mas, which functions “as interactive entities that animate our inherent theatrical nature, derived from traditional ritual and an understanding of how to assert ourselves in space to the beat of the drum,” makes us reconsider the idea of the monumental, since “our entry into art-making is inherently multimedia and contemporary.” Chan adds that Minshall's chosen art form is one that “he has continually had to define and devise how to explain or exhibit.” In that sense, she agrees that “it is monumental to underline that art coming out of Carnival and performance is equal to what is considered contemporary art.”

A timeline of Minshall's work. Photo by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

“Minshall's work is the most significant of our time in the Caribbean,” she continues. “It is a moment where we could underline this genre coming out of the Caribbean in relation to contemporary art on a global scale. Minshall's work has been written about by key curators, theatrical researchers, anthropologists, and fellow artists and creatives. We must acknowledge this work and its value to our country and culture [and] preserve this massive archive for future generations to understand the work and study it about our time.”

In the 10 weeks that the exhibition has been open to the public, over 5,000 people have passed through. To Chan, the most phenomenal aspect was visitors’ feelings when entering the space: “The joy is the stories we collected, testimonies of people who were there in 1974.” One of those visitors was 92-year-old Joan Gomez, who shared her memory of the moment Minshall's hummingbird first took flight.

Various articulations of Minshall's ‘From the Land of the Hummingbird’ costume. Photos by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

“The show had almost come to an end [and] they were looking for a queen. Costumed children were dancing around in an elliptical circle [in front of the judges]. And suddenly, everything went still. You could have heard a pin drop. When you looked to the east, you just saw this hummingbird standing, glittering in the sun, all the little feathers blowing in the wind. And suddenly the children separated […] the whole of the North Stand, the Grand Stand rose [as] she started to dance. Applause. You [have] never seen such a spectacle as that. When I tell you, it was beautiful; you can’t imagine. Immense pleasure. A real hummingbird. Every little detail. It was really something out of this world.”

Written by Janine Mendes-Franco

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.