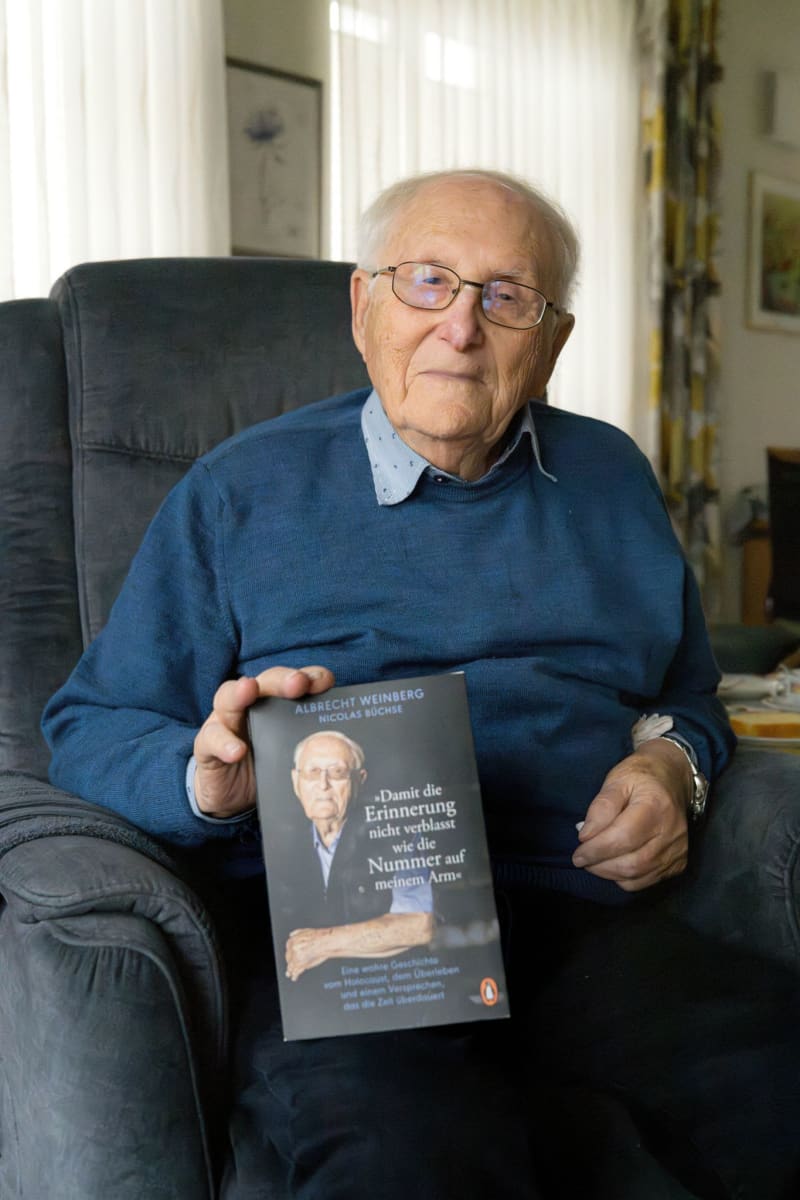

The number on Albrecht Weinberg's left forearm is clearly visible even some 80 years later: 116,927.

Albrecht Weinberg sees the slightly faded tattoo when getting ready for the day every morning - and with it come the memories of Auschwitz.

"It's unbelievable that something like that really happened," the 99-year-old says looking back on the Holocaust, when Germany's Nazi regime systematically murdered more than 6 million Jews across Europe, plus many other minorities and dissidents.

Weinberg, who emigrated to the US after surviving the unspeakable horrors of Nazi persecution but has since moved back to the north-western German town of Leer, was tattooed with the number when being deported to Auschwitz, the most notorious concentration camp run by the Nazis, in April 1943.

He has long remained silent about the horrors he lived through, but now Weinberg is one of the few remaining Holocaust survivors alive who are able to tell their stories.

Together with a journalist from German news magazine Stern, he has written down his life's story and turned it into a book, titled "So that the memory doesn't fade like the number on my arm."

In it, he recalls how anti-Semitism began to spread in his native East Frisia region on the Dutch border in the 1920s and early 1930s before the Nazis came to power in 1933.

Slowly, his Jewish family found themselves found themselves more and more marginalized from public life, until the November pogroms of 1938 ripped them apart for ever.

The Nazis almost completely wiped out Weinberg's family - his parents, uncles, aunts and cousins were all killed. Only he and his two siblings would survive.

Weinberg himself somehow made it through three concentration camps - Monowitz, also known as Auschwitz III, Mittelbau-Dora in Thuringia and Bergen-Belsen near Celle - as well as several death marches, common in the later stages of World War II when the Nazis began to flee from approaching allied forces.

'A truly exceptional person'

A photographer who works with survivors of the Bergen-Belsen camp introduced Weinberg to Stern journalist Nicolas Büchse.

"He called me and said, 'Man, you need to meet this Holocaust survivor. He's truly an exceptional person'," Büchse recalls.

The journalist had interviewed several Holocaust survivors before but they tended to be reserved exchanges and he was reluctant to press closer, fearful of overstepping their boundaries.

But Weinberg immediately offered him the "du," the informal German address usually reserved for family and friends.

"There was an immediate closeness that is extraordinary, especially for someone who has experienced so much," Büchse recalls.

Following countless interviews and trips with Weinberg, his feature grew into a book.

Weinberg's life story is one of the creeping dehumanization of a society, says the journalist, a process that many say is visible in Germany again today for example with the surge in polls of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party or a more general increase in anti-immigrant rhetoric.

"If you listen to Albrecht, you can gain the ability to recognise these warning signs more precisely," Büchse says.

Despite the torment he experienced, Albrecht Weinberg's memories are crystal clear, for example of the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen camp. "At the time, I was a Muselmann," says Weinberg, using a term common among inmates at the time to refer to those suffering from both starvation and exhaustion. "A man covered in bones and skin, not an ounce of flesh."

When British soldiers liberated the camp on April 15, 1945, he was more dead than alive, surrounded by piles of corpses and weighing just 29 kilograms. "Then the tanks drove in. I thought I was going to be released," says Weinberg, who repeatedly intersperses his sentences with English words. "We never believed that we would be liberated. We thought we would all be shot."

Returning to Germany some 40 years later

In total, around 52,000 people died in the camp and immediately after liberation, in addition to almost 20,000 deaths in the neighbouring prisoner of war camp. Albrecht and his two siblings Friedel and Dieter who survived the atrocities.

After liberation, they found each other again, but were only given little time together, as Dieter died in an accident in 1946.

Friedel and Albrecht, only in their early 20s at the time, emigrated to New York in 1947 to start a new life, certain that they would never to return to Germany. "We never wanted to see or hear anything about Germany again," says Albrecht.

Some 40 years would go by before they would set foot in the country again that so thoroughly ripped their family apart, when the city of Leer invited them to come in 1985.

Further visits soon followed, and slowly friendships began to form.

When Friedel's health began deteroriating in 2012, they finally returned for good.

Albrecht remained by her side until she died in a care home briefly after their arrival.

During that time, he met carer Gerda Dänekas, who finally convinced him to start talking about the horrors lived through in the past, journalist Büchse says.

Dänekas was convinced that talking about the horrors would not only benefit those who had not lived them, but also Weinberg himself, he says.

Ever since, Weinberg has tirelessly been telling his story. Until recently, he regularly visited schools to tell students about the genocide he survived.

"I have seen that I am doing a good thing by letting them know what can happen to them and their future," says Albrecht Weinberg.

The secondary school in his native village of Rhauderfehn has since been named after him.

Class trip at almost 100 years of age

It took Weinberg decades to open up about the atrocities experienced in the past. Even Steven Spielberg, who asked for an interview in the 1990s, did not change his mind. He was always afraid that others did not want to listen to his memories.

Until this day, the 99-year-old maintains that no one can understand what he went through - not even he himself. Weinberg therefore listens to radio documentaries again and again, and Gerda Dänekas reads him newspaper articles and books about the Holocaust.

Anti-Semitic incidents occurring today are still difficult to bear for the Holocaust survivor.

When gravestones were knocked over at the Jewish cemetery in Leer a few days ago, Albrecht withdrew into his room. "I didn't want to know anything, I went to my room and thought about how it had never been any different for me: the hatred and the discrimination."

Even 80 years after the Holocaust, police in Germany are still stationed to protect synagogues. "I can't believe it," Weinberg says.

He and Gerda moved into a shared flat for senior citizens. "It's the best thing I've ever done," says Gerda, who is now retired. Many people advised her against it, but she never regretted the decision, on the contrary. They both travel, have been to New York and even went on a school trip to Israel with a local class in 2022.

They want to start giving readings soon. It feels great to be part of Gerda and her family now, says Weinberg. "I've never had it this good in my life."