In the arid landscape of Arabia, archaeologists don’t usually find a lot of artifacts. The heat dries organic matter, making it fragile and unlikely to preserve. However, researchers found an unexpected ally in a lava tube. According to a recent study, humans have been taking refuge in this lava tube for over 7,000 years, leaving behind numerous artifacts and art pieces.

Lava and ancient shepherds

A lava tube is a natural tunnel-like formation. The top part of the lava flow cools down and solidifies, while the molten lava beneath continues to flow beneath this hardened crust. This creates a hollow, tube-like structure that can vary widely in size and length.

This is also the case of Umm Jirsan. This is essentially a system consisting of three lava-tube passages separated by two collapses. It measures 1481.2 m in length (just under a mile) and has a height of 8-12 m (26-39 ft).

The site has been known to the Saudi Geological Survey for decades now, and local people have of course known Umm Jirsan forever. That said, the site had never been properly investigated or surveyed by palaeontologists or archaeologists. Its recognition as an archaeological site is new,” says Mathew Stewart, the lead researcher and a Research Fellow at Griffith University’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution (ARCHE), for ZME Science.

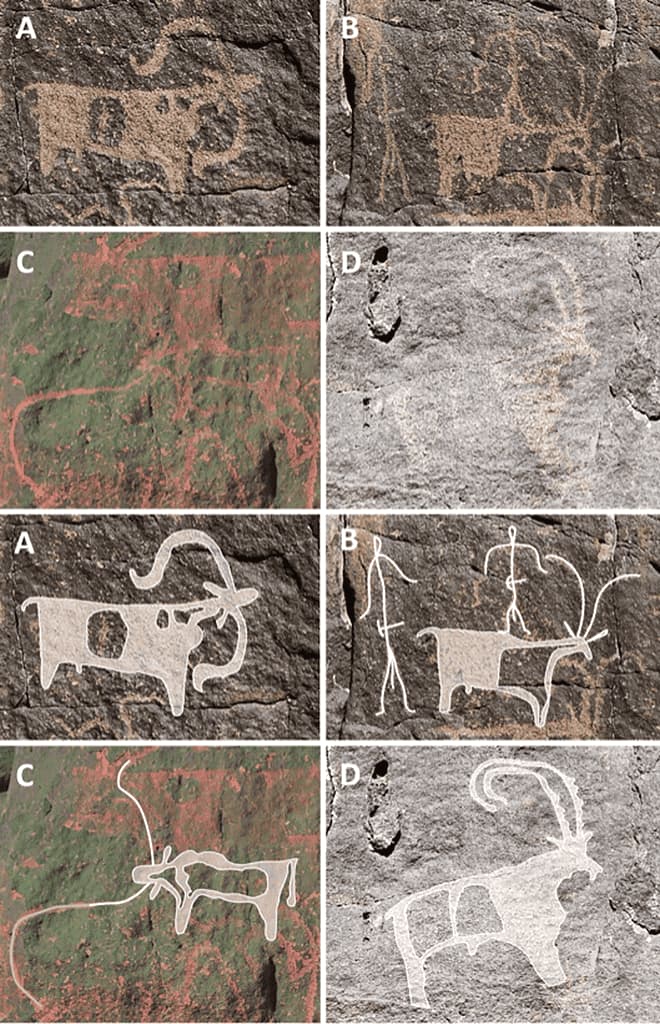

Stewart and colleagues found a wealth of archaeological evidence at Umm Jirsan. The earliest of these dates to around 10,000 years ago, and the latest to some 3,500 years ago. They found depictions of cattle, sheep, and dogs — a testament to the pastoral past of these populations. However, the lava tube was probably not inhabited continuously.

Temporary shelter

The density of artifacts is relatively low. This suggests people didn’t stay at the site continuously. Instead, they used it as a temporary hideaway. People (especially shepherds) traveling between different oasis settlements likely used it as a stopping point. In the harsh desert, having access to such a stopping point would have been invaluable.

“Based on the low density of lithics recovered from the excavation, as well as from the surrounding landscape, we suspect that visitation to the site may have been rather transitory. It’s clear that people knapped stone tools on site, as well as lit fires and cooked and processed food. “

The research team also used isotopes to reconstruct the diets of humans and animals on the site.

These isotopes accumulate in the tissues differently depending on the types of foods consumed. For instance, in the context of the archaeological studies at Umm Jirsan, isotopic analysis of animal remains helped the team determine that livestock primarily grazed on wild grasses and shrubs, characterized by specific isotopic signatures.

Similarly, the analysis of human remains reveals a diet rich in protein and increased consumption of “C3 plants“, indicating a shift towards oasis agriculture. This technique provides a detailed picture of dietary habits and environmental adaptations, offering insights into agricultural practices and the ecological conditions of past civilizations.

More to be discovered

Modern archaeology is a lot about figuring out what people used to live like. Sure, you can still find amazing structures and uncover artifacts, but archaeologists are increasingly interested in the lifestyles of ancient populations. This type of study is not new — but it’s new for Saudi Arabia.

“While underground localities are globally significant in archaeology and Quaternary science, our research represents the first comprehensive study of its kind in Saudi Arabia,” added Professor Michael Petraglia, Director of ARCHE. “These findings underscore the immense potential for interdisciplinary investigations in caves and lava tubes, offering a unique window into Arabia’s ancient past.”

Arabia’s past hides a rich occupation of thousands of years and we’ve only started to scratch the surface of what lies in the ground, just waiting to be discovered.

Sure, the sun and the heat are enemies of archaeologists. But lava tubes and other natural shelters can provide a record of the populations that called the area home.

“The area boasts a rich Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological record, as evidenced in the thousands of stone structures that can be found dotting the landscape. This is, however, the first documented evidence of human occupation of such a site in northern Arabia. It suggests that underground sites were important areas of habitation but ones that have until now been overlooked. These and other cave sites provide huge potential as places where there is good preservation of organic remains such as bone and deeply stratified sediments.”

Journal Reference: Stewart M, Andrieux E, Blinkhorn J, Guagnin M, Fernandes R, Vanwezer N, et al. (2024) First evidence for human occupation of a lava tube in Arabia: The archaeology of Umm Jirsan Cave and its surroundings, northern Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 19(4): e0299292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299292

Was this helpful?

Thanks for your feedback!

This story originally appeared on ZME Science. Want to get smarter every day? Subscribe to our newsletter and stay ahead with the latest science news.