By Spoorthy Raman

In eastern Sierra Leone, straddling the border of Liberia, lies Gola Rainforest National Park, one of the last remaining intact tracts of the tropical Upper Guinean forests in West Africa. Towering trees with massive buttress roots create a dense, emerald-hued canopy where monkeys hoot, malimbes chatter and hornbills flutter between the branches with their high-pitched honks and impressive wingspans.

Along the park’s fringes, 122 communities own small patches of the jungle within the four-kilometer-wide (2.5-mile) buffer zone. In the past, people here relied on these community forests to harvest timber and other forest produce, hunt for bushmeat and grow staple crops.

In the 1900s, logging and mining intensified in the region’s forests, including the area that would become Gola Rainforest National Park. People cut down large swaths of trees in the buffer zone to grow cash crops like oil palm and cacao, from which chocolate is made. Poaching and encroachment in the forest increased during Sierra Leone’s civil war in the 1990s and into the early 2000s, further threatening the rainforest and its wildlife. According to a 2017 geospatial analysis published by Purdue University in the U.S., such activities led to massive deforestation, with the Gola community forests losing more than 4% of their tree cover annually between 1991 and 2016.

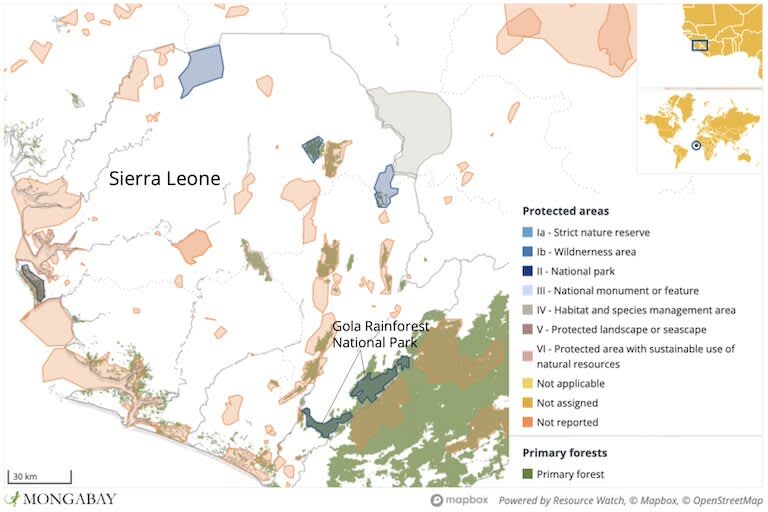

Gola Rainforest National Park sits on Sierra Leone’s border with Liberia and protects one of the country’s last large tracts of primary forest.

In 2013, a carbon credit project was launched in the Gola rainforest to stymie deforestation and provide a sustainable, alternate livelihood for forest-dependent communities. The 30-year project follows the United Nations-backed framework to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) by managing forest resources sustainably and enhancing forest carbon stocks. Companies, countries and other entities can purchase carbon credits through the program and use them to offset their emissions and meet the targets of the Paris Agreement, which aims to slow global warming enough to thwart its worst effects. In return, the forest-rich, low-income tropical countries receive monetary benefits for conserving their forests and safeguarding biodiversity.

The 30-year Gola REDD+ carbon project began as a collaboration between the U.K.’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), which has been working in Gola since the 1980s; the Conservation Society of Sierra Leone (CSSL), one of the country’s oldest conservation organizations; and the government of Sierra Leone. Their joint venture, the Gola Rainforest Company–Limited by Guarantee (GRC-LG), sells carbon credits and works with the forest-edge communities — the project’s beneficiaries — to enact conservation measures.

Gola rainforest: A biodiversity hotspot

Spanning more than 740 square kilometers (286 square miles), about twice the size of the U.S. city of Detroit, the picturesque Gola rainforest teems with life. More than 60 threatened species, including many endemic to the Upper Guinean forests, call these forests home.

“It is one of the richest biodiversity areas in the world,” says Fiona Sanderson, a principal conservation scientist at the RSPB who has studied the biodiversity of the Gola rainforest for more than a decade.

The rainforest harbors a dozen primate species, including Diana monkeys (Cercopithecus diana) and western red colobus monkeys (Piliocolobus badius), more than 300 species of birds, including endemic rufous fishing owls (Scotopelia ussheri) and yellow-casqued hornbills (Ceratogymna elata), and a dizzying array of butterflies. The forest is also a refuge for western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus), African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis), pygmy hippos (Choeropsis liberiensis) and giant pangolins (Smutsia gigantea) — all of which are threatened.

“Some of them are fantastic specimens of nature [and] they are very, very attractive,” says Sierra Leonean conservation biologist Hazell Shokellu Thompson. “If we lose the Gola forest, we will certainly lose quite a number of these animals and birds in this region, not only from Sierra Leone but also from West Africa.”

African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) are listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

The rainforest stores some 19 million metric tons of carbon, and the REDD+ project is expected to result in emissions reductions of around 550,000 tons of CO2 per year. “It is a large tract of rainforest that is acting as a huge carbon sink,” Thompson says. “It is important for avoided emissions [and] for our battle against climate change.”

The REDD+ program aims to trade this stored carbon to save the rainforest and its impressive biodiversity.

Forest-friendly cacao: Reviving livelihoods and protecting forests

A major component of the Gola REDD+ project is establishing forest-friendly cacao plantations within the buffer zone around the national park. Although not a native species to the region, cacao has been grown in Sierra Leone since the British colonial era and is a crop that farmers rely on for income. Nearly 70% of the world’s cacao comes from smallholders in West Africa, particularly Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, where large swaths of forests are cut down to make way for monoculture plantations.

In partnership with the RSPB, the Gola REDD+ project encourages farmers to grow shade-loving cacao under the canopy of native rainforest trees such as Ivory Coast almond and African teak (iroko). Cacao relies on native insects, bats and birds for pollination and pest control.

According to the RSPB, 2,587 farmers living in the forest fringes cultivate more than 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) of forest-friendly, shade-grown cacao as part of the REDD+ project. In 2020, 44 metric tons of cacao was grown in these farms. Apart from cacao, farmers also grow kola nuts, coffee and vegetables.

Research suggests cocoa crops produce higher yields if grown under the canopies of rainforest trees. Image by Fiona Sanderson.

These agroforestry patches don’t just provide food and income for forest communities — they also act as corridors and habitat for wildlife in areas that would otherwise be cleared for conventional agriculture, according to the RSPB.

“What we are trying to do is flip it on its head,” Sanderson says of the forest-friendly cacao plantations. “It creates a kind of forest-like structure with the same native trees.” She says that more than 100 native tree species are found in these agroforestry plots, and nearly half of them have potential economic value — a key driver for agroforestry.

The cacao plantations are also a haven for wildlife, according to researchers. A study conducted by Sanderson and colleagues and published in Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment in 2022 recorded more than 140 bird species in Gola’s shade-grown cacao plantations, of which nearly 60% were forest-dependent species such as hornbills. Many plantations had more native species than the threshold required for sites to qualify as Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas — a designation given by BirdLife International that signifies the potential of a site for bird conservation. Chimpanzees, monkeys and forest elephants also venture into the cacao plantations to raid crops, much to the chagrin of local farmers.

As a cash crop, cacao generates revenue for farmers. However, access to better-paying markets hasn’t been easy. As part of the Gola REDD+ project, the GRC-LG has set up cooperatives within the communities where farmers, as members, can sell their beans at a premium. The beans are then exported to international markets, where their selling price is higher than what the middlemen visiting the communities offer. Through the cooperatives, farmers receive training on best practices to improve cacao yields and adopt forest-friendly cultivation practices.

A farmer in a Gola community works in a shade-grown cocoa plantation. Image by Michael Duff.

“Forest-friendly cacao is quite a unique program because it is encouraging shade-growing cacao by providing a premium or a bonus for farmers [which] incentivizes them to be a part of the program,” says social scientist Natasha Constant at the RSPB. She says preliminary results indicate cacao production contributes to 69% of farmers’ incomes. “The merit in this scheme is that … the income generated through agroforestry cacao can be almost twice as high as that of monoculture.”

Benefits galore for forest-edge communities

Since the inception of the Gola REDD+ project, the GRC-LG has partnered continuously with the seven Gola chiefdoms and their member forest-edge communities in the spirit of obtaining free, prior and informed consent, as enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). According to GRC-LG representatives, paramount chiefs and the communities that are part of the REDD+ benefit-sharing agreement have the final say in how the funds are used.

“During the development of the REDD+ carbon project, we went into community consultation, participatory meetings and assessment,” says Fomba Kanneh, who heads the GRC-LG and who grew up in a Gola forest-edge community. “We did [a] need[s] assessment with all the communities — looking into the historical profile of the area and what they used to do before the commencement of the program.”

As a result of these consultations, the Gola REDD+ project was expanded to provide scholarships, uniforms and books for students, set up a savings-and-loan scheme for women-owned small businesses, invest in building schools and hospitals, and provide training for farmers to increase their crop yields so they don’t have to slash and burn additional patches of the forest to feed their families. Growing forest-friendly cacao was also a choice the communities made.

“Before the REDD+ project, communities were involved in mining, logging and poaching for money, but now it is hard to access these resources,” Kanneh says. “So, the communities have agreed to develop a beneficiary agreement that pays a royalty for conservation.” Kanneh adds that the GRC-LG has 56 rangers who regularly monitor and patrol the park for deforestation, logging, poaching, mining and other illegal activities.

A member of the Malema Cocoa Farmer’s Association weighs his cacao produce at the cooperative. Image by Michael Duff.

Sheku Kamara, executive director of the Conservation Society of Sierra Leone, says the project links conservation to livelihood. “The dependency on the forest is for people to get their livelihood. So if you can provide them something of an alternative, where they can increase their income, they will be less dependent on the forest,” he tells Mongabay. “Livelihood is a tool that we use in conservation.”

These principles have translated into results, according to a recently published 2024 study in Nature Sustainability that found that in its first five years, the Gola REDD+ project reduced the average annual deforestation rate in the buffer zone by 30% compared to areas that weren’t part of the REDD+ project. This reduction in deforestation translates to 340,000 metric tons of avoided CO2 emissions.

“We’re not removing deforestation [through the REDD+ project]; we’re just reducing it,” study co-author Maarten Voors, an economist at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands and who is not affiliated with the Gola REDD+ project, tells Mongabay. He attributes this reduction to forest-friendly cacao plantations. “To a large extent, they’re not clearing the dark green stuff — the important trees, the big ones that have sequestered a lot of carbon — they’re leaving those aside and doing other activities.”

The study also found that the reduction in deforestation didn’t affect people’s incomes. “We didn’t see win-win, but we saw a win-no loss,” Voors says.

A small cocoa plantation coexists with rainforest in the Gola region. Image by Fiona Sanderson.

The Gola REDD+ project isn’t without its challenges. Kamara tells Mongabay the carbon credit market tends to be volatile and can impact the revenues generated for the communities. Bringing together over more than 100 communities with different priorities and needs requires years of hard work, trust and transparency in benefit-sharing. Shashi Kumaran, head of sustainable financing at the RSPB, says imparting financial literacy to farmers to manage their cacao farm business can be challenging. Cacao yields, although promising, can vary, pushing farmers to resort to more lucrative but forest-harming activities like logging, according to the RSPB’s Sanderson. She adds that deforestation in the buffer zone can spike during periods of economic instability, as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite these challenges, those involved in implementing the Gola REDD+ project say they see a bright future for it because the communities see the benefits and appreciate the efforts put in by the different partners.

“You don’t have conservation without people, and we want a landscape that delivers for everyone because the communities living within them are absolutely [an] integral part of the landscape,” Sanderson says.

Banner image of a western red colobus monkey (Piliocolobus badius) by user peterichman via Wikimedia Commons (CC 2.0).

Feedback: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Citations:

Abu-Kpawoh, J. C. (2017). Deforestation in Gola forest region, Sierra Leone: Geospatial evidence and a rice farmer’s expected utility analysis (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI10274611/

Wessel, M., & Quist-Wessel, P. M. F. (2015). Cocoa production in West Africa, a review and analysis of recent developments. NJAS–Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 74-75(1), 1-7. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2015.09.001

Sanderson, F. J., Donald, P. F., Schofield, A., Dauda, P., Bannah, D., Senesie, A., … Hulme, M. F. (2022). Forest-dependent bird communities of West African cocoa agroforests are influenced by landscape context and local habitat management. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 328, 107848. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2021.107848

Malan, M., Carmenta, R., Gsottbauer, E., Hofman, P., Kontoleon, A., Swinfield, T., & Voors, M. (2024). Evaluating the impacts of a large-scale voluntary REDD+ project in Sierra Leone. Nature Sustainability, 7(2), 120-129. doi:10.1038/s41893-023-01256-9

This article was originally published on Mongabay