By Sarah Brown

Brazil’s Pará state has now protected almost all of its Amazonian coastline after establishing two new conservation units that make up the world’s largest and most conserved belt of mangroves. The environmental victory came after President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva signed the decree for the two reserves on March 21, placing an additional 74,700 hectares (184,600 acres) of mangrove ecosystems under federal protection.

“It’s another win for us to protect this mangrove here in the Amazon,” Sandra Regina Pereira Gonçalves, fisherwoman and national director and regional coordinator of the National Commission for Strengthening Extractive Reserves and Traditional Coastal and Marine Extractive Peoples (Confrem), told Mongabay. Confrem was involved in the campaign for getting the mangrove regions recognized as federal reserves.

The creation of the reserves is an important milestone for guaranteeing food security for local populations as well as preserving the area’s rich biodiversity and aiding carbon sequestration. Getting the reserves recognized as federally protected areas took 16 years and faced several setbacks, Gonçalves said, including a freeze between 2019 and 2022 on environmental protection initiatives by former president Jair Bolsonaro.

The two new reserves are the Filhos do Mangue and the Viriandeua extractive reserves. Known in Brazil as Resex, extractive reserves are conservation areas where community residents maintain the right to traditional extractive practices, such as hunting, fishing, and harvesting wild plants. They’re designed to protect the livelihoods and cultures of traditional people and ensure the sustainable use of an area’s natural resources.

“Only community members can live from the local biodiversity,” Monique Galvão, vice president at Rare Brasil Institute, a nonprofit involved in the process leading to the creation of the reserves, told Mongabay. “It means that big companies from the private sector cannot be there, for example.”

The Filhos do Mangue Resex covers 40,537 hectares (100,169 acres) and is home to 4,000 families; the Viriandeua Resex spans 34,191 hectares (84,488 acres) with almost 3,100 families. The two reserves are in the Salgado Paraense region that supports one of the largest and most ecologically important mangrove forests in the country.

“With the creation of Filhos do Mangue and Viriandeua, we have here a formation of a great shield, a great area of protection of the Amazonian mangroves,” Mauro Pires, president of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), the federal agency that oversees protected areas, said in a video statement. “[These mangroves] are rich in biodiversity and provide a way of life to numerous families that benefit from these resources.”

On March 21, the International Day of Forests, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva signed decrees creating two new conservation areas to protect Pará’s mangroves. Image © Claudio Kbene/Agência Brasil.

Protecting Brazil’s mangroves

As well as being home to hundreds of wildlife species and sustaining thousands of people, the mangrove forests at the mouth of the Amazon River help combat climate change. Mangroves are among the most carbon-rich ecosystems in the world, storing about 1,000 metric tons of carbon per hectare in their roots and surrounding soil.

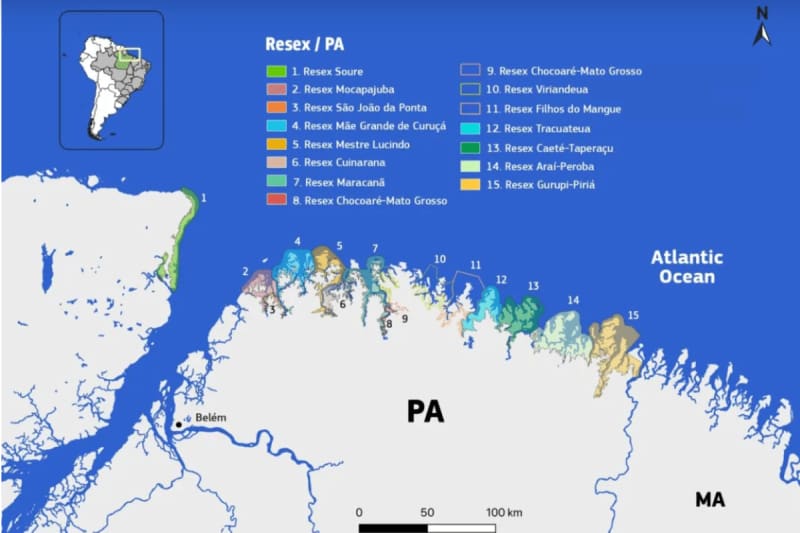

Brazil’s coastal mangroves cover an area of about 1.4 million hectares (3.5 million acres), making up about 10% of all the remaining mangroves in the world. Most of these mangroves are concentrated on the Amazon coastline, with 80% of all Brazilian mangroves found in three Amazonian states: 505,490 hectares (1.25 million acres) in Maranhão, 390,589 hectares (965,166 acres) in Pará, and 226,895 hectares (560,670 acres) in Amapá. In Pará, almost all the mangroves are now protected within 14 federal conservation areas.

ICMBio estimates that 25% of Brazil’s mangroves have been lost since the beginning of 1900, especially in the southeast and northeast of the country. In the northeast, saltwater aquaculture, especially shrimp farming, is a crucial source of income and employment for rural populations, but can have a negative effect on mangroves. Although this region isn’t directly affected by the conversion of mangroves to shrimp ponds, shrimp farming still indirectly impacts the ecosystem through pollution and degradation.

“We want to avoid that from happening in the north,” Galvão said. “With this protection [in the two new reserves], it prevents big companies from setting up business in those areas to extract nature, and also to prevent the threat of oil, gas and shrimp production.”

The protected mangrove reserves along the mouth of the Amazon in the state of Pará, including the two newest ones: Viriandeua (10) and Filhos do Mangue (11). Image © Rare Brasil Institute.

In the Brazilian Amazon, the livelihoods of traditional coastal communities are based on artisanal fishing, crabbing, and harvesting of other natural resources, collecting what they need to support their families. According to a 2014 study, these traditional lifestyles “help maintain the nearly pristine condition of the mangroves and impede the conversion of forests for the establishment of shrimp farming operations.”

About 90% of Brazil’s fishers are small-scale. Most live in the north of the country and fish in and along the Amazonian mangroves. The reserves in this region, including the two new ones, ensure that these traditional methods are maintained, which helps safeguard the mangroves.

“In addition to the natural resilience of the extensive Amazon mangroves, conservation units, especially Resex, bring an additional layer of legal protection, because they are managed in a participatory manner by traditional fishing communities, which help to define forms of sustainable use of Amazonian mangroves,” Pedro Walfir Souza Filho, a geologist and associate researcher at the Vale Institute of Technology, told Mongabay.

The creation of the reserves also provides local communities with extra insurance in the event of future oil activity in the north of Brazil. There are an estimated 30 billion barrels in the Equatorial Margin at the mouth of the Amazon, and state-owned oil giant Petrobras plans to explore offshore sites here off Amapá state — a plan that environmentalists have warned would bring widespread and far-reaching damage should an oil spill occur.

The oil exploration plan is being debated at a federal level, with President Lula in favor of it, although Petrobras has not yet been granted the necessary licensing to conduct research in the region. While the creation of the new reserves doesn’t prevent the possibility of oil exploration, having the management plans and records of the beneficiaries means it would be much easier to provide assistance and protection to populations impacted by any future oil spills. Environmentalists say they hope the government of Amapá will follow the example of Pará in preserving its coastal mangroves.

“The government of Amapá is also aligned with the government of Pará,” Galvão said. “I’m very positive that Amapá could be another priority place for us in terms of protection.”

The two new reserves help strengthen the protection of Pará’s coastline from oil spills, which environmentalists warn could be a risk if the government authorizes oil exploration off the coast of neighboring Amapá state. Image © Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace.

Managing the reserves

Managing the extractive reserves takes a participative approach, with input from several stakeholders. A deliberative council is created, made up of representatives of government agencies, civil society organizations, and traditional populations residing in the area. This council approves the management plan for the Resex.

The next step for the Filhos do Mangue and Viriandeua reserves is to define this management plan to ensure that the conservation areas are for sustainable use only. This means no large-scale economic activity in the Resex; only sustainable production for the benefit of the traditional populations living there.

“This process is really long because it involves many stakeholders and different expectations,” Galvão said. It’s a rigorous procedure that includes mapping out who can benefit from the natural resources in the Resex. Beneficiaries need to register, and if they meet the profile defined by the council, are “allowed to capture wealth in a sustainable way from nature,” Galvão said.

With the victory of increasing the protection of Pará’s Amazonian coastline, community members say they now hope to secure more reserves along Brazil’s mangroves. “We are the protectors of the mangroves, we call ourselves the guardians of the sea,” Gonçalves said. “We want to go to other states, too, so that they can also do what Pará is doing, protecting the mangroves and the communities.”

Banner image: Almost all of Brazil’s mangroves, 80%, are found in three Amazonian states: Maranhão, Pará and Amapá. Image © Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay