China’s unique approach to acquiring access to Kazakhstan’s uranium is the focus of a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace policy brief that does not align with Western policymakers’ usual view of how Beijing engages with developing nations.

In particular, the policy paper—titled To Secure Kazakhstan’s Uranium, Chinese Players Were Compelled to Accommodate Local Partners—underscores Kazakhstan’s own approach to the engagement, which meant China had to follow Kazakhstan’s rules.

The research ultimately treats Kazakhstan as a case study among multiple other examples of China having to work with existing developmental models within different nations.

“Chinese banks and funds are exploring traditional Islamic financial and credit products in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, and Chinese actors are helping local workers upgrade their skills in Central Asia. These adaptive Chinese strategies that accommodate and work within local realities are mostly ignored by Western policymakers in particular,” notes the policy brief’s author, Yanliang Pan, a researcher at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

“China’s economic relationship with Kazakhstan is often framed in clichéd narratives associated with Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, in which Kazakhstan represents the ‘buckle’ of the land-based economic belt connecting China and Europe,” Pan—whose research often focuses on the intersection between geopolitics and international nuclear energy commerce—notes. “As the largest country in Central Asia, Kazakhstan is unquestionably critical to Beijing’s vision of westward connectivity, but reducing Kazakhstan to no more than a node in Beijing’s transregional geoeconomic strategy obscures Chinese actors’ adaptive approach to Kazakhstani local interests while overlooking the gains that Kazakhstani actors themselves have skillfully extracted in key sectors of engagement with China.”

As such, Pan points out the cooperation between China and Kazakhstan in uranium extraction and nuclear fuel supply as a “prime example” of such a dynamic, as it demonstrated Chinese actors having to navigate Kazakhstan's terms rather than imposing their own.

Uranium dominance

Kazakhstan stands out as the world's largest producer of natural uranium. It contributed to 43% of global uranium production in 2022, the policy paper notes. Kazakhstan's rich uranium reserves have geological characteristics that make the deposits particularly conducive to low-cost, high-profit extraction using in-situ leaching (ISL) methods. Boasting two-thirds of the world's ISL-suitable reserves and nearly 80% of ISL-derived natural uranium supply as assessed in 2022, Kazakhstan enjoys a significant cost advantage.

As a result, it state-run nuclear company, Kazatomprom, has emerged as one of the most competitive uranium producers globally, wielding substantial bargaining power over foreign uranium companies seeking access to Kazakhstan's cost-effective resources, Pan posits.

Kazatomprom’s production volumes surged to approximately 25,000 tU in 2016 and the company aims to boost the figure further to 31,000 tU by 2025. Since the Central Asian nation does not rely on its own uranium domestically—that will remain the case at least until Kazakh authorities follow through with plans to build a nuclear power plant—all of its mined uranium is exported.

Feeding China’s uranium cravings

China is the world’s second-largest producer of nuclear energy and has a rapidly expanding civilian reactor fleet. Unlike the US, which has seen only a modest amount of new reactor installations constructed in recent decades, China has maintained a robust pace in nuclear construction, with most of its ongoing reactor projects initiated during a building spree that started in 2022. To secure natural uranium supply for its burgeoning nuclear industry, China has adopted a comprehensive strategy termed “four-in-one,” which includes domestic and overseas mining, international purchases and reserves.

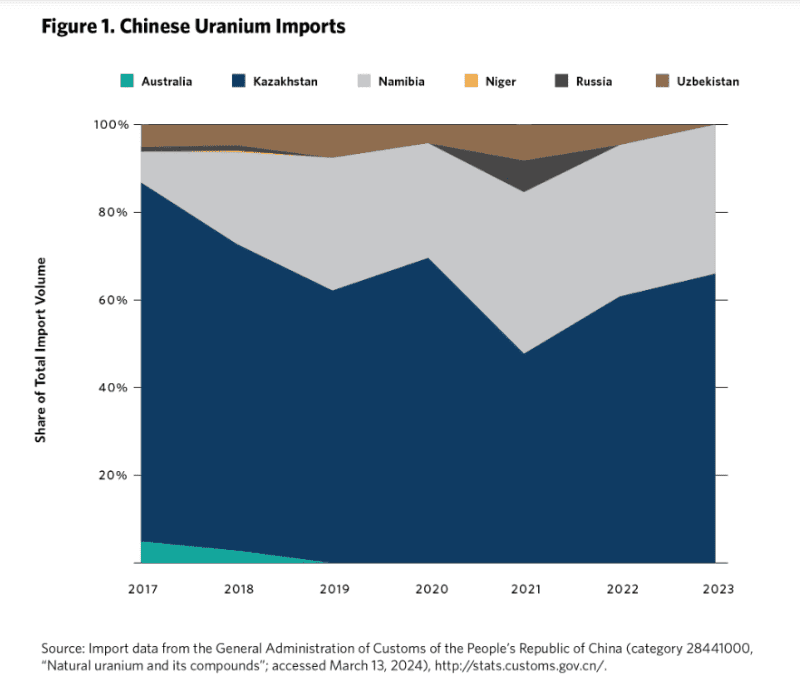

China has been procuring natural uranium from Kazakhstan since the early 2000s. Despite Chinese companies having uranium purchase agreements with various suppliers globally, logistical constraints often lead Western suppliers to obtain their material from Kazakhstan for delivery to China. Chinese customs data from 2023 indicate that nearly all of the country's imported natural uranium originated from Kazakhstan and Namibia, with Kazakhstan alone contributing two-thirds of the volume.

“Through a flurry of agreements between 2006 and 2008, the Chinese company [China General Nuclear Power Group (CGN)] succeeded in securing through its subsidiary a 49 percent stake in Semizbay-U—a joint mining venture with Kazatomprom. Then, another wave of agreements between 2014 and 2016 laid the foundation for CGN to take over a 49 percent stake in the Ortalyk joint venture from Kazatomprom in 2021,” Pan mentions.

While, on the surface, these acquisitions might seem similar to those in Namibia, they differ significantly due to distinct local norms, expectations and bargaining power, the analyst emphasises. For instance, unlike in Namibia, where CGN holds a 90% stake in the Husab mine with just 10% allocated to Epangelo, the Namibian state-owned uranium mining company, CGN and its subsidiaries have never held a majority stake in any Kazakh mining venture. Even after the implementation of a 2017 law stipulating Kazatomprom's minimum ownership at 50 percent, CGN's involvement remained below majority ownership.

Pan’s study points out that Kazatomprom's joint mining venture deals and offers of uranium access typically come with expectations of assistance in vertical integration, such as technology transfers, in explicit quid pro quo arrangements.

Failure by foreign partners to fulfill these expectations may lead to the withdrawal of resource access, as seen in 2016 when Kazatomprom reduced its Japanese partners' shares in Kazakh joint mining ventures when they failed to deliver promised technology transfers, the report says.

In line with such expectations, CGN's access to uranium was conditioned on its ability to provide Kazatomprom with opportunities for vertical integration. Agreements signed in 2006 and 2007 between the two companies stipulated that all natural uranium produced by joint ventures would be delivered to China as high-value nuclear fuel products.

This arrangement allowed Kazatomprom to access China's nuclear fuel market and profit from high-value fuel fabrication, the policy brief concludes. While ambitious cooperation agreements with Japanese-owned Westinghouse and France's Areva for fuel assembly manufacturing at Ulba were suspended due to market shifts, CGN seized the opportunity to invest in the Ulba fuel fabrication plant in exchange for a stake in the Ortalyk joint mining venture.

Pan presents this case study as a valuable lesson for future Western engagement in Central Asia and around the world, while also arguing that it could “help China’s own policy community learn from the diversity of Chinese experience; and potentially reduce frictions”.