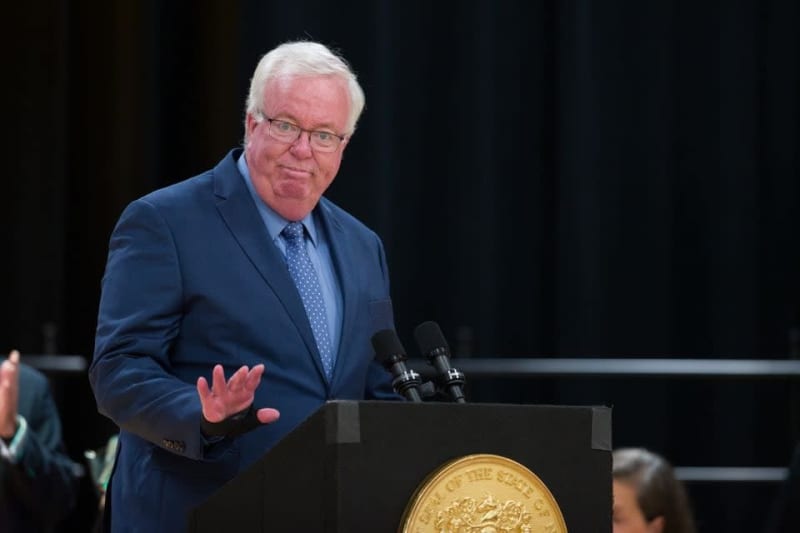

Business is booming for New Jersey Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin.

An attorney by profession, Coughlin was a low-key state lawmaker with a solo law practice and a handful of municipal clients in the years before he ascended to the third most powerful position in the Statehouse in 2018.

No less meteoric is the rise of the law firm he co-founded as he lined up for that leadership post.

Established with a couple of well-known partners, Rainone Coughlin Minchello has seen explosive growth in the seven years since it opened its doors. Representing local governments across the state, the Woodbridge firm has earned more than $38 million from public contracts since its inception, with annual revenues that now place it among New Jersey’s top law firms with public business, financial disclosures show.

This year, Coughlin, a Middlesex County Democrat, marked a historic milestone when he became the state’s longest-serving Assembly speaker ever, holding huge influence over any legislation the chamber takes up. With the rise of his law firm coinciding with that power, good government groups call Coughlin’s financial ties troubling, saying they raise questions about whether he is profiting from his public role from municipalities seeking a friend in the speaker.

“Elected officials are there to serve the people, and not also to reap the benefits of doing so on the other side of things,” said Heather Ferguson, the director of state operations for Common Cause, a Washington-based public advocacy group. “You don’t need to make money both ways.”

In a prepared statement, the firm touted the experience of its lawyers in representing government entities and noted Coughlin’s work as an attorney predated his political career.

“We are proud of the firm’s 22 attorneys who have established significant expertise in the practice of municipal law,” the firm said. “We are equally proud of the trust placed in the firm by the bipartisan roster of mayors, councilpersons, commissioners and executive directors that seek our advice.”

In 2017, Rainone Coughlin Minchello had public contracts worth $1.9 million, with 30 municipalities, authorities and public insurance funds as clients, financial disclosures show. Those earnings have grown every year since, with the firm making $8.3 million from 70 local governments last year — a more than fourfold increase in its revenues.

As a founding partner, Coughlin benefits financially from that work, though the list of clients he represents himself is modest: his hometown of Woodbridge, where he has served since 2002 as a municipal lawyer; the redevelopment agency of South Amboy, the city where he grew up; and several library boards, according to his professional biography.

In an interview in January, as he was preparing to be sworn in to another term as speaker, Coughlin said he understands the criticism surrounding the firm but stressed that “it’s not the whole picture.” He noted that he started the firm before he became speaker, that his two partners had their own clients before that, and “that’s the way we really grew.”

The firm’s two other namesakes are Louis Rainone, a prominent municipal attorney who was once law partners with the late former Assembly Speaker Alan Karcher, and David Minchello, whose clients include Plainfield, Morristown, Scotch Plains and the Union County Improvement Authority.

“Those guys had many of those contracts long before they came to the partnership,” Coughlin said. “And I think we do really good work.”

In Trenton, Coughlin is known as affable and even-handed, often described as the adult in the room in a Statehouse famous for standoffs and feuds. His career has also not carried the whiff of scandal that follows many New Jersey politicians. Still, some see his law firm’s business as emblematic of the state’s political culture, where public service and private gain often intersect.

“If you think that his being part of the firm has no impact on the fact that they’re getting this business, then I guess it doesn’t matter,” said Julia Sass Rubin, a professor at Rutgers’ Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy. “That seems a little unlikely.”

Is the above chart not displaying? Click here.

Others cast it as the typical give-and-take of political life and note that Coughlin’s partners are well regarded.

“If they’re competent at what they do, towns are going to hire somebody, right?” asked Marc Pfeiffer, another professor at the Bloustein School. “And if you’re buying services from somebody, you want to maximize the services you’re going to get. Why shouldn’t I have a law firm that has influence?”

New Jersey’s 120-member Legislature is part-time, earning $49,000 a year, though Coughlin receives a third more — $65,333 — as speaker. In January, lawmakers gave themselves a big raise: They’ll make $82,000 a year come 2026, with the speaker’s salary jumping to about $109,000.

The vast majority of the legislators hold outside jobs, including many that potentially touch upon their elected roles. And with the law a dominant profession in the two chambers — 31 members are attorneys — Coughlin isn’t alone. His counterpart in the state Senate, President Nick Scutari, for instance, has been a municipal prosecutor and personal injury attorney and has faced criticism in the past for advancing legislation seen as friendly to trial attorneys.

At least eight other lawmakers work as lawyers advising municipalities or other government entities, including Senate Republican leader Anthony Bucco of Morris County, according to an NJ Advance Media review of financial disclosures and professional biographies.

Bucco said municipal law is all he practices, and he cast his work experience as an asset, saying it helps him to be a better legislator. The towns he represents — Roxbury, Netcong and Mine Hill — are all longtime clients, he said, with all but Mine Hill predating his time at the Statehouse.

He said those towns know not to try to mix his legal services with his political role.

“That’s implied. It goes without saying,” Bucco said. “And when there’s an issue that I can’t deal with because it presents a conflict, I tell them that.”

Assemblyman Gregory McGuckin, R-Ocean, has also spent decades as a municipal lawyer, a career that, like Bucco and Coughlin’s, began before he was in the Legislature. Among his current clients are Toms River, his district’s largest community, where he is township attorney.

McGuckin said he sees no conflict in his dual hats.

“What’s good for a community is good for my district, that’s the way I look at it,” he said. “But there’s strict ethics rules on what we can and can’t do on behalf of a public entity as a legislator, and I make sure we follow this.”

McGuckin added: “I’ve been doing it for years and years before I ever got in the Legislature. I don’t think I should be penalized for it, for being elected.”

Yet activists and political analysts note that as speaker, Coughlin has an outsized influence that poses unique challenges, since any bill must have his support to make it to Gov. Phil Murphy’s desk. And much of the Legislature’s work is of deep interest to municipalities, from state aid to affordable housing legislation, to earmarks that fund parks, playgrounds and bus terminals.

“He’s in a position to advance Murphy’s agenda or bury Murphy’s agenda,” said Carl Golden, a former press secretary to Republican Govs. Tom Kean and Christie Todd Whitman. “It’s understandable people want to look at his private business and be skeptical about the amounts of money and his leadership position.”

“People will ask: If he wasn’t the speaker, would his law firm hold all these contracts and do all this work for public agencies?” Golden said.

The firm’s clients deny they’ve received a leg up at the Statehouse because of the business relationship.

“I’m proud to be one of Craig’s good friends, and I’m proud of the job he does in Trenton,” said Woodbridge Mayor John McCormac, who has known Coughlin for over 30 years. “And I would stand up for his integrity any day of the week.”

Coughlin has long served as the attorney for Woodbridge’s township council, a job he has continued to perform despite his duties as speaker. McCormac said those roles aren’t in conflict.

“We would never want to put Craig in a position where he was criticized for benefiting Woodbridge, so we simple don’t,” said McCormac, a former state treasurer. “And we have plenty of other avenues and relationships in Trenton to get what we need.”

The scrutiny comes as New Jersey has been embroiled recently in a number of good government fights that will shape everything from how voters select their candidates for state and federal offices, to how political campaigns are financed, to how easy it is for residents to obtain government records.

In each case, Coughlin is a key figure in the direction the state takes. And in each, Rainone Coughlin Minchello has its own interest in the outcome, given its business and the clients it represents.

The county line

Last month, a federal judge issued an injunction against New Jersey’s one-of-a-kind primary ballot system, which critics have long said gives an unfair advantage to candidates backed by the political parties.

The ruling sent shockwaves through New Jersey’s political establishment, where the ballot design — known as the “county line” — has been a cornerstone of the power structure in a state known for party bosses and machines.

Before U.S. District Court Judge Zahid Quraishi issued his decision, leaders of the Legislature from both aisles — including Coughlin — insisted changes should be made by lawmakers, not the courts. They did so as they vowed to launch a bipartisan public discussion on the ballot’s design, a move that critics dismissed as too little, too late.

At the same time, Rainone Coughlin Minchello was representing the Mercer County Clerk’s Office, one of the defendants in the lawsuit seeking to uphold the controversial system.

Campaign finance reform

Last year, the Legislature overhauled New Jersey’s campaign finance laws, raising overall contribution limits for the first time in two decades and weakening pay-to-play prohibitions that seek to prevent public contractors from winning business by opening their checkbooks.

Since 2017, Rainone Coughlin Minchello has given nearly $817,000 in political contributions, according to its annual pay-to-play disclosures. Much of that money has gone to candidates and committees in communities that the firm represents, a review by NJ Advance Media found.

Last year, the firm gave $210,300, its most ever. That placed it among the top 10 donors with public contracts in the state, and as the top donor among law firms with public business.

!function(){"use strict";window.addEventListener("message",(function(a){if(void 0!==a.data["datawrapper-height"]){var e=document.querySelectorAll("iframe");for(var t in a.data["datawrapper-height"])for(var r=0;r<e.length;r++)if(e[r].contentWindow===a.source){var i=a.data["datawrapper-height"][t]+"px";e[r].style.height=i}}}))}();

Is the above chart not displaying? Click here.

OPRA overhaul

Lawmakers are considering a bill that would revamp the Open Public Records Act, New Jersey’s two-decade-old law that allows the public to access a wide range of government records, from contracts, to emails to police body camera footage.

Sponsors say the measure would bring the statute into the digital age by better protecting residents’ personal information, putting more records online and reining in abuses by commercial “data brokers.” But last month, lawmakers pulled the bill to rework it after backlash from advocacy groups, news media and public sector unions who charged the changes would gut the law and add to government secrecy.

“I am inspired that so many people have taken an interest and engaged in this legislation,” Coughlin said in a statement after the proposal was scuttled, adding that lawmakers were “working on various amendments to ensure we get the bill right.”

As a firm that represents governments, Rainone Coughlin Minchello offers legal advice to a raft of municipalities and other public entities facing public records requests.

In written questions, NJ Advance Media asked Coughlin and Louis Rainone, the firm’s managing partner, how they address instances where the firm represents government agencies with an interest in the outcome of legislation. Written statements from the firm and Coughlin’s office did not address those questions.

One client of Rainone Coughlin Minchello said the firm draws a bright line of separation between its work and access to the speaker. North Brunswick’s longtime township attorney is Ronald Gordon, who joined Rainone Coughlin Minchello several years ago after working for another law firm.

“Ron has always made clear that if we have legal questions, talk to him,” said Mayor Francis “Mac” Womack. But If the township has political business, “don’t ask Mr. Gordon to intervene with Mr. Coughlin on our behalf.”

Womack said he is unaware of any instance in which the township’s relationship with the firm has given it an advantage. He said he recently met with Coughlin over flood damage to North Brunswick’s municipal building sustained in 2021 during Hurricane Ida, but went through the speaker’s office to set up the meeting and left with no promises.

“I got the same 20 minutes anyone else would get,” Womack said.

Womack is a lawyer, and he said he knows firsthand the potential pitfalls of elected office and a private career: He is township attorney in South Brunswick and said he also does municipal work in South Amboy.

“An attorney who holds a public office and also does work in the public sector has to be extremely careful and accountable,” Womack said. That involves avoiding situations where their decisions “are going to be affected by what they do on the other side.”

Womack said concerns about the dual roles are valid, but that it is possible to strike a balance.

“I think you can, but I do believe you have to be vigilant,” Womack said. “I sure hope you can, because I enjoy what I do.”

Our journalism needs your support. Please subscribe today to NJ.com.

Riley Yates may be reached at ryates@njadvancemedia.com. Follow him on X at @riley_yates

Brent Johnson may be reached at bjohnson@njadvancemedia.com. Follow him on X at @johnsb01.