-Analysis-

BEIRUT — With their toned bodies and tight shirts, designer watches and luxury cars, social media has been invaded by the phenomenon of young males who, with their short videos, present themselves as the one true standard of success.

These people break the rules of decorum imposed by society, having achieved wealth and financial independence by following the “grinding” method for living (which is synonymous with “carving in rock” in our Arab popular language), and adhering to “authentic” ideas and beliefs. At least this is how they describe it.

For the latest news & views from every corner of the world, Worldcrunch Today is the only truly international newsletter. Sign up here.

Such ideas are tied to the conservative popular heritage about the role of men and women, where the man is the protector and provider and the woman is responsible for raising the family.

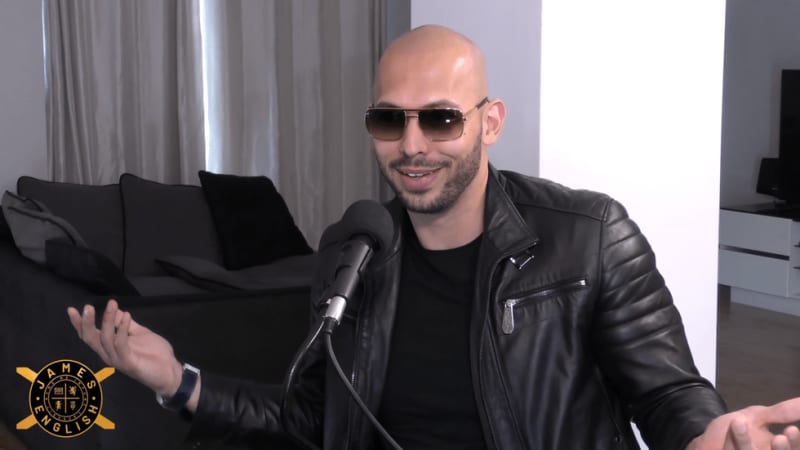

The phenomenon reached its peak in 2021 when the name of the British-American former boxer Andrew Tate, who can be considered the father of this phenomenon in its modern form, topped lists as the most searched name around the world.

The invasion of this phenomenon on the Arabic-speaking internet arrived a bit later, starting with the translation of Tate’s videos into Arabic. Since then, a whole cadre of Tate imitators and wannabes have appeared, mirroring his attitude and appearance into an Arab context. Perhaps the best-known example is Miami-based Jordanian Jalal Abu Muwais, whose videos have received tens of millions of views on social media platforms.

Patriarchy of self-made millionaires

These internet personalities share very similar stories: The self-made millionaire who used to work in bakeries and slept on the streets before he became wealthy. He does not have time for feelings, and he urges his followers to ignore them, and focus on working harder, earn more money, and most important of all: to subscribe in his “closed community” online or buy his “courses” that help males (and males only) to become rich and powerful men, just like him.

The audacity and entitlement to express their opinions on everything

These characters have the audacity and entitlement to express their opinions on everything from breakfast (Tate calls the meal “the worst thing that will ever happen to humanity.”) to university (which Abu Muwais considers merely a “social experiment”) to the way a man should treat his partner, his brother and mother.

They believe that the elites and traditional and social media have destroyed the world by “destroying masculinity” and “distorting femininity.”

Who's a man?

The discourse of these figures is based, to a large extent, on a highly individual approach to self-improvement and how to link this to creating and preserving wealth. Instead of any intelligent analysis or providing services or actual steps that the wealth-seeker can benefit from, they focus their “motivations” on emphasizing that the viewers are inferior to them. They despise and rebuke them.

They do not offer advice as much as just show off what they have achieved, as a kind of urgent need for self-esteem in the eyes of others using phrases like Tate’s “You are a loser,” or Abu Muwais’ “Jalal is not like you.”

This new type of populism is not limited to stereotyping gender roles and delegating men to guardianship over women, and in some cases, blaming the latter for being exposed to violence, whether physical or virtual.

These figures are not ashamed to attack men considered not “patriarchal” enough: from those who use e-cigarettes, spend a lot of time with his children, share bills with his wife, or complain about his worries to his mother is a clumsy person, “not a man,” according to them.

Alpha male perfection

What makes the content of these internet personalities so tempting and attractive to millions of viewers is that the image of masculinity they market is one still deeply rooted in traditional patriarchal imaginations. They are considered the modern embodiment of the idea of the “alpha male,” the man who takes control, always knows what he's doing and makes everyone wait for him. This is built on the idea that he has become infallible, after the mistakes he committed in the past that led him to where he is today.

They also tickle people’s imaginations through their lavish consumer culture: sports cars, private jets, luxurious mansions, expensive vacations.

Your masculinity is required to fight all the changes that are happening in a world that is no longer yours.

Robert Lawson, author of the book “Language and Mediated Masculinities,” says that one of the best explanations for why young men in particular are attracted to the model of masculinity presented by these characters is the American sociologist Michael Kimmel’s idea of “oppressed entitlement," that says the world has changed over the last 20 years in a way that has undermined the centrality of males in society at economic and material levels, and their participation with women in work, education, and various aspects of the public sphere.

People like Tate or Abu Muwais are attractive because they change young people’s thinking in a very clear and simple way: “You matter, a lot is still required of you, and your masculinity is required to fight all the changes that are happening in a world that is no longer yours and is no longer wants to invest in you.”

On one hand, our ancestors used to support an entire family with one salary. Today a middle-class family can barely survive without two salaries.

On the other hand, women no longer have to depend on men financially or emotionally. Internet personalities essentially say they will fight this, not by offering economic solutions or at least a critique of what capitalism has become, but by restoring a sense of traditional, “authentic” masculinity. This story goes back even to the 1980s.

The crisis of the young masculine body

Much of what these characters say is not actually new. It is a reworking of the crisis of masculinity discourse that the United States experienced in the 1970s and 1980s, through the “men’s movement.” There was a prevailing feeling that reconnecting with masculinity was a way to fix the world.

For centuries, society has grappled with the question of what to do with anxious young people.

What we see today is just the latest in a long line of other men who have done similar things. For centuries, society has grappled with the question of what to do with anxious young people.

Yet today, modernity presents a unique combination of circumstances: brutal and merciless inflation, a widening gap between wages and costs, a crisis in male body image, and “motivators” who despise young people and exacerbate their problems, presenting a superficial vision of eternal youth, showing a life devoid of responsibilities.

The past in this type of life includes an “inspiring story.” There is nothing about a future to worry about. And the present? It's just a platform for fleeting pleasure.