By Fernanda Wenzel

In Mato Grosso do Sul state, around 100 Indigenous individuals from the Guyraroká community of the Guarani-Kaiowá people are confined to an area of 50 hectares (123 acres) on the edge of a road, surrounded by soybean and corn plantations. Meanwhile, in Minas Gerais state, the Krenak are fighting to reclaim the area where their cemeteries and sacred sites are located.

They still experience the effects of the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964-85, when Indigenous peoples were tortured, enslaved and forced from their territories. “The state will always be indebted to us, Indigenous peoples,” says Erileide Domingues, a young leader at the Guyraroká Indigenous land.

In early April, the Krenak and Guyraroká communities received the first collective amnesties in the country’s history — previously, amnesties had only been granted on an individual basis. The recognition was established by the Amnesty Commission attached to the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship, which was created in 2002 to shed light on the dictatorship’s crimes. It is a formal apology from the Brazilian state.

“The recognition of collective reparation will not erase the incarceration, murders and torture committed,” Brazil’s Minister of Indigenous Peoples Sonia Guajajara wrote on X (formerly Twitter). “But it is an important step toward memory and justice, and a way for us to mark the severe persecution we suffered during that very violent period in Brazil’s history.”

For the leaders of both peoples, however, true reparation will come when their territories stolen by the Brazilian state are returned.

Guarani-Kaiowá elders attended a session in which the Brazilian state asked for their forgiveness for the crimes committed against their people during the military dictatorship. Image courtesy of the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI).

“We understand that the commission’s apology is valid, emblematic and symbolic. But it won’t serve the Krenak people if it remains only as symbolic,” explains Geovani Krenak, leader of the Krenak Indigenous land in Minas Gerais. “It has to come with actions that aim to demarcate the Sete Salões Indigenous land in order to minimize the trauma suffered during the dictatorship,” he adds, referring to the territory of around 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres) that was stolen from them.

The Krenak people experienced a succession of violations throughout the military regime. In 1969, the federal government and the Minas Gerais state government created the Krenak Indigenous Agricultural Reformatory by the Doce River in Resplendor, Minas Gerais. There, Indigenous people were starved and tortured, as described in the amnesty request signed by the Federal Prosecution Service.

The forced move to the Guarani farm in the municipality of Carmésia, in 1972, also had devastating effects, according to reports collected by the prosecutors. “It was even worse when they arrived at the Guarani farm, because they couldn’t live off hunting and fishing as they used to do in their own land. There wasn’t even a river in the Guarani farm, and the climate was completely different, much colder than the land they had always occupied before they were expelled,” Geovani says.

Geovani’s grandfather Jacó was one of the elders who could not bear the longing for his homeland and died at the Guarani farm. His father, who died in 2010, was tied to a horse and dragged through the village. Anyone who spoke the original language or danced traditional dances was punished.

“My father used to tell that story with lots of anger; he was very angry at the military, and I think this caused him trauma. It was very hard for him to remember it,” says Geovani.

In 2021, a Federal Court in Minas Gerais ordered that the Sete Salões Indigenous land be delimited within six months. The following year, however, the Indigenous affairs agency (Funai) — still during the administration of former President Jair Bolsonaro — filed a request to suspend enforcement of the sentence. Now, the Krenak want the agency to withdraw that request.

“It’s unacceptable that the Brazilian state apologizes and then Funai keeps this request,” Geovani says.

For Erileide Domingues from the Guyraroká Indigenous land, the horrors of the dictatorship are also alive in the stories told by her grandfather, Indigenous leader Tito Vilhalva. As a young man, he had to abandon his land after being enslaved by farmers who said they had bought the area “with the bugres in it” — a racist reference to the Guarani-Kaiowá.

The community still struggles to recover the territory. Meanwhile, they are squeezed between massive soybean and cornfields, and they suffer contamination from pesticides dropped by airplanes onto neighboring plantations.

“Without our territory, we can’t have anything. We can’t produce our own food, we can’t talk about health, education, well-being. Without our territory, it’s as if we were fish out of water,” Domingues says.

According to information provided by the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI), the demarcation of the Guyraroká Indigenous land was annulled by Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court in 2014, based on the time frame thesis, according to which Indigenous peoples would have to prove they were living in the territory before the 1988 Constitution to be entitled to land. The Indigenous people appealed, and the case is ongoing.

The Avá-Canoeiro on the brink of extinction

Even before the military dictatorship, Indigenous people were seen by the Brazilian government as obstacles in the way of large infrastructure projects and the expansion of the agricultural frontier. The Avá-Canoeiro, who live in the Araguaia River region in Tocantins, are known to have put up the fiercest resistance to colonization, and they paid a high price for it.

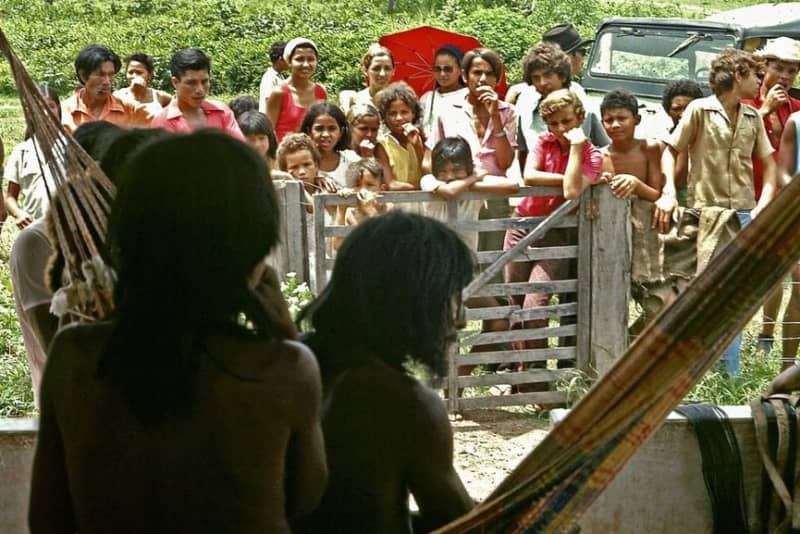

After decades of fleeing the advance of miners and farmers, in 1973, they were victims of forced contact by Funai, whose agents arrived shooting at them. After being arrested, they were exhibited for six months as animals on one of the largest farms in the area. “People came from all over the place to see those people who had been captured,” says Patrícia de Mendonça Rodrigues, an anthropologist in charge of the report that identified the territory of the Avá-Canoeiro.

After forced contact, the Avá-Canoeiro Indigenous people were exposed like animals at the Canuanã Farm in 1973. Image courtesy of Klaus Gunther.

From there, the group was taken to live in the territory of the Javaé Indigenous people, their historical enemies. During that period, the ethnic group was reduced to just five members. Rodrigues, who interviewed survivors from that period, says they do not even like to remember that time.

“So five individuals were living on the outskirts of the village of an Indigenous people of whom they were historical enemies. And they lived in that situation for almost 50 years, being marginalized politically, culturally and economically,” she says.

Today, there are more than 40 Avá-Canoeiros living in the Araguaia River region. In April 2023, the Federal Regional Court of the 1st Region (TRF-1) upheld a lower court decision ordering the Brazilian state to pay collective moral damages for violations committed against them.

However, their fight for their own territory is not over. The Taego Ãwa Indigenous land has been recognized and demarcated by the federal government, but it has to be officially confirmed, and non-Indigenous occupants still have to be removed.

In late March, TRF-1 set a 15-month deadline for Funai to complete the procedure, and 12 months to remove the settlers and farmers occupying the area.

Funai was contacted for comments but did not respond until this story was published.

Banner image: Leaders of the Guyraroká community in Mato Grosso do Sul are still fighting to recover their territory stolen during Brazil’s military dictatorship. Image courtesy of Christian Braga/Farpa/Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

This story was reported by Mongabay’s Brazil team and first published here on our Brazil site on Apr. 18, 2024.

This article was originally published on Mongabay