Antarctic animals are at risk of being ‘sunburnt’ as the ozone hole opens for longer, scientists have warned, and climate change could be to blame.

As if the impact of global heating on sea ice weren’t bad enough, penguins, seals and other wildlife are also being exposed to harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation during their summer.

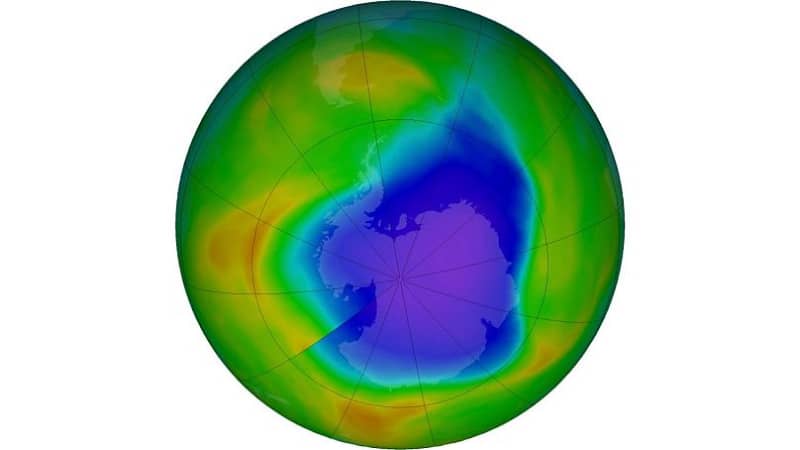

Ozone gas forms a protective layer in the Earth’s upper stratosphere. The realisation that some chemicals - primarily chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) used as refrigerants - were depleting it led to a major intervention in 1987: the Montreal Protocol.

It is widely considered to be the world’s most successful environmental treaty, and UN experts say the ozone layer is on track to recover within decades.

But climate change could disrupt that healing journey. The ‘hole’ that opens over Antarctica every year has, for the last few years, been closing later than usual.

Animals and plants are paying the price, according to a new study published in the journal Global Change Biology, which explores their different coping strategies.

Why is the ozone hole staying open for longer?

The ozone layer over Antarctica wears thin every Southern Hemisphere spring, as the climatic conditions - extreme low temperature, high atmospheric clouds - are ripe for ozone-eating chemical reactions to occur.

This annual event typically peaks in September and October and patches up during November. But since 2020, the ozone holes have been closing later, around mid to late December.

This has been due to colder than average stratospheric temperatures and a strong polar vortex (circulation of strong winds) lasting for longer, the EU’s atmosphere monitoring service said last year.

Scientists are still figuring out exactly what’s causing this stronger polar vortex, but it bears the fingerprints of climate change.

The new study points to the amount of particles released during the catastrophic Australian wildfire season of 2019-2020, fuelled by climate change. A quarter of the country’s temperate forests went up in smoke, killing or displacing three billion animals.

The La Soufrière and Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcanic eruptions in 2021 and 2022 - which injected huge amounts of water vapour into the stratosphere - could also have contributed to the larger hole sizes in recent years.

How are Antarctic animals reacting to the UV exposure?

In spring, most land-based plants and animals are shielded by snow cover, while marine life is protected by extensive sea ice. But with the ozone hole lasting into the Antarctic summer, creatures are being exposed to damaging UV-B rays.

These rays increase the risk of cancer and cataracts in humans, and could cause similar eye damage for penguins and seals. This is likely their most vulnerable body part, as outer coverings of fur and feathers reflect UV radiation or act as a barrier, the study explains.

The researchers gathered together the latest research on how UV is impacting polar life.

Antarctic mosses, for example, are synthesising their own kind of sunscreen compounds. This might sound remarkably resilient but, as co-author and climate change biologist Professor Sharon Robinson told BBC News, “There's always a cost to sun protection.”

“If they're putting energy into sunscreen, they're putting less energy into growing,” she said.

Krill - the tiny, abundant marine creatures at the bottom of the Antarctic food chain - appear to be moving deeper into the ocean to avoid UV rays. This could hit the whales, seals, penguins and other seabirds that feed on them.

"We also know that the phytoplankton that the krill feed on will have to make sunscreens in order to avoid damage,” Prof Robinson said.

The start of summer is peak breeding season for many animals, and so extreme UV-B exposure may come at a vulnerable time in their life cycle, the study points out.

It makes the case that UV impacts need to be looked at in combination with other effects of climate change - particularly shrinking sea ice.

"The biggest thing we can do to help Antarctica is to act on climate change,” Prof Robinson added. Namely, “reduce carbon emissions as quickly as possible so we have fewer bushfires and don't put additional pressure on ozone layer recovery."