Gallimimus is a theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Mongolia, dating from around 70 million years ago. Discovered during the 1960s through Polish-Mongolian expeditions in the Gobi Desert, Gallimimus stands out as the largest known ornithomimid, a group of bird-like dinosaurs. Unlike most ferocious theropods of its time, Gallimimus was vastly different—it grazed in groups and sprinted at high speeds to evade danger. This article aims to explore the discovery, anatomy, and lifestyle of Gallimimus.

In This Article

Discovery and History

The discovery of Gallimimus dates back to the mid-20th century during Polish-Mongolian paleontological expeditions in the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Between 1963 and 1965, these collaborative efforts led to unearthing the first Gallimimus fossils. The most significant find occurred in 1964 when a large, well-preserved skeleton was excavated by Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska and her team, laying the groundwork for the genus’ formal description.

In 1972, paleontologists Halszka Osmólska, Ewa Roniewicz, and Rinchen Barsbold officially named and described the new genus and species, Gallimimus bullatus. The genus received the name Gallimimus, the “chicken mimic”, due to the resemblance of its neck vertebrae to those of modern-day birds, specifically the Galliformes. The species name, bullatus, refers to a bulbous structure at the base of its skull, likened to a Roman bulla).

The findings from these expeditions were revolutionary, providing the most complete and well-preserved ornithomimid specimens known at the time. Therefore, Gallimimus emerged as a key figure in the ornithomimosaur group, representing one of the best-known and most thoroughly researched genera.

Physical Description

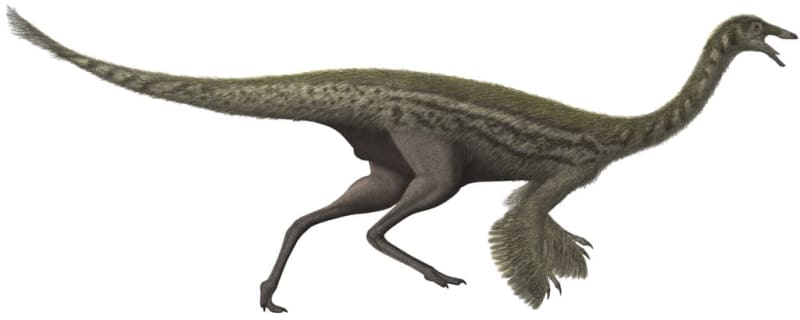

Gallimimus is the largest known ornithomimid. It grew up to 6 meters long and stood 1.9 meters tall at the hip. With an estimated weight of 400 to 490 kilograms, its physique was streamlined for speed. The discovery of feathered relatives suggests that Gallimimus likewise sported a feathered coat, hinting at a more bird-like appearance than previously imagined.

The dinosaur’s head was small and lightweight, with large eyes positioned to the sides, granting it a wide field of vision—essential for spotting predators or prey. Unlike many of its theropod relatives, Gallimimus’ snout was elongated, and its jaws were devoid of teeth, replaced by a beak, likely covered in a keratinous sheath. This adaptation suggests a varied diet, further mystified by the presence of small, columnar structures within the beak, whose purpose remains a topic of debate among scientists.

Gallimimus’ neck was remarkably long, resembling modern-day chicken and ratites, enabling it to forage over a larger area with minimal movement. While relatively short compared to its body, it had three-fingered hands, each tipped with curved claws. Despite the potential for grasping, the delicate structure of these limbs suggests they were not heavily relied upon for feeding.

In contrast, its hindlimbs were a marvel of evolutionary engineering, designed for speed. The long, powerful legs culminated in feet with three forward-facing toes, ideal for rapid, sustained running similar to an ostrich. Estimates suggest Gallimimus could reach speeds of up to 56 km/h, making it one of the fastest dinosaurs of its time.

Behavior and Lifestyle

One of Gallimimus‘ most striking anatomical features is its skeletal pneumaticity, most of its bones were hollow. This adaptation, common among birds, suggests a highly efficient respiratory system, potentially correlating with a high metabolic rate and the energetic demands of a fast-running lifestyle. This cursorial capability indicates a lifestyle adapted to quick movements across open landscapes. Several Gallimimus fossils found together suggest that it lived in groups, which could have facilitated collective foraging and enhanced predator evasion.

Although Gallimimus’ precise diet is still debated, certain physical adaptations hint at an omnivorous lifestyle. The discovery of columnar structures within the beak has drawn comparisons to the lamellae found in the beaks of some modern waterfowl, which use them to strain food from water. However, this filter-feeding hypothesis is not without its challenges. The columnar structures in the beak could also have been used for feeding on tough plant material, similar to the ridges found in the beaks of turtles and hadrosaurs.

The evidence of gastroliths in some ornithomimid specimens further complicates the picture. The gastrolith — also called a stomach stone or gizzard stone, is a rock held inside a gastrointestinal tract — is often associated with animals that consume tough plant material, aiding in the mechanical breakdown of food in the absence of mastication. While not directly found with Gallimimus fossils, their presence in related species suggests a potential herbivorous component to its diet.

Development and Growth

Juvenile Gallimimus specimens indicate a rapid growth rate, a characteristic common among theropods. The proportions of the skull and limbs in juveniles differed significantly from those of adults, suggesting changes in feeding behavior and mobility as they grew.

Gallimimus‘ skull also underwent significant changes throughout its development. A juvenile’s skull was proportionally larger and its snout was shorter compared to adults. As Gallimimus matured, the snout elongated, and the eyes moved slightly. These adaptations may have improved its ability to forage or hunt for food. These changes also reflect shifts in dietary preferences or feeding strategies as Gallimimus aged.

The limbs of Gallimimus also showed significant growth, with the legs lengthening and strengthening to support its fast-running lifestyle. The discovery of growth rings in Gallimimus bones has provided valuable information on its lifespan and growth rate. These rings also suggest that Gallimimus‘ growth phases fluctuated with seasonal changes or food availability.

Classification and Evolution

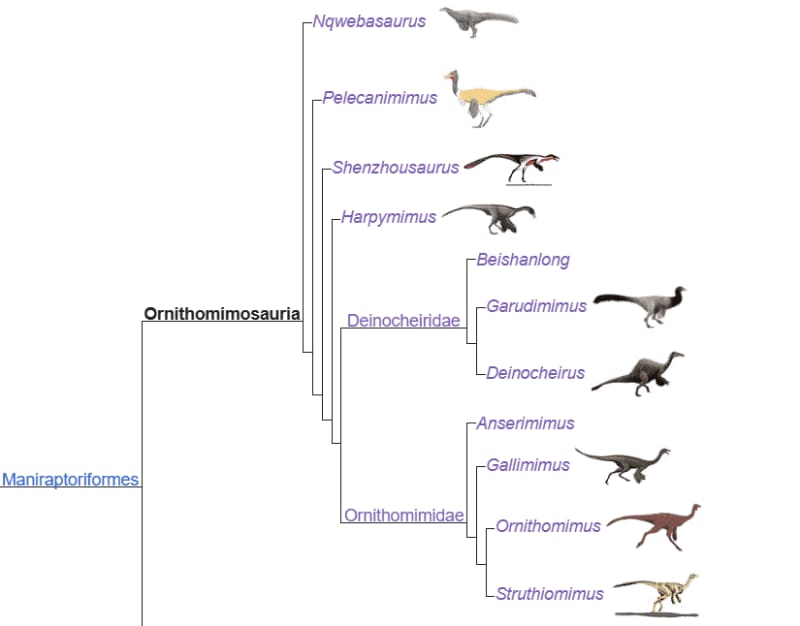

Gallimimus bullatus belongs to the Ornithomimidae family, known for its bird-like features and long limbs. Ornithomimids evolved various bird-like traits, such as beak-like mouths and probable feathering, reflecting convergent evolution with birds. Gallimimus’s specific features, the elongated snout and limb proportions, differentiate it within its family, indicating a unique evolutionary path.

Close relatives like Anserimimus, also from Mongolia, suggest a localized diversification of Asian ornithomimids. This regional evolution showcases the adaptive radiation of these dinosaurs in response to environmental conditions and available niches. Paleontologists describe ornithomimosaurs as a clade characterized by swift, bipedal locomotion, and omnivorous feeding habits. This group’s evolution mirrors broader trends in theropod development towards avian characteristics.

Paleoecology

Gallimimus lived in the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia, approximately 70 million years ago. A mix of river channels, mudflats, and shallow lakes characterized this environment. The various sediments found within this formation indicate an environment subject to periodic changes, such as seasonal droughts. Despite these challenges, the region teemed with life. The waters teemed with fish, turtles, and crocodylomorphs like Shamosuchus, while birds such as Gurilynia and Judinornis soared the skies.

On land, Gallimimus shared its environment with a diverse assembly of dinosaurs. Predatory theropods like the ‘alarming’ Tarbosaurus and the nimble troodontids Zanabazar stalked the landscape. At the same time, large herbivores including relatives like Deinocheirus, ankylosaurids like Tarchia,and hadrosaurids like Saurolophus grazed side by side. For Gallimimus, the varied terrain and abundant water sources would have provided ample feeding opportunities, whether it browsed on plants, hunted small animals, or filter-fed. The social behavior inferred from fossil groupings suggests that the genus may have lived in flocks, akin to modern-day birds.

Gallimimus in Popular Culture

Gallimimus is no stranger to popular culture as its memorable appearances in film and video games made it one of the most recognizable dinosaurs to audiences worldwide.

Probably Gallimimus‘ most memorable appearance is in the “Jurassic Park” franchise. A flock of Gallimimus is depicted sprinting across a field as they are being hunted by Tyrannosaurus rex. The flock almost trampled Dr. Grant and the kids as they could not outrun these agile dinosaurs. Gallimimus also has brief features in the franchise’s future installments, “Jurassic Park: The Lost World” and “Jurassic World”.

Disney’s “Dinosaur” features Gallimimus briefly as a part of the herd seeking the nesting grounds through the desert. One of the “chicken mimics” succumbs to exhaustion and is scavenged by raptors.

Gallimimus is no stranger to video games as well. “Jurassic World Evolution” allows players to build and manage their own dinosaur theme parks, featuring Gallimimus as one of the main attractions.

In “ARK: Survival Evolved”, Gallimimus is a tameable creature, serving as a rapid mode of transportation for players navigating the world. Its exceptional speed and ability to carry multiple riders make it highly valued for exploring and escaping predators within the game.

Was this helpful?

Thanks for your feedback!

This story originally appeared on ZME Science. Want to get smarter every day? Subscribe to our newsletter and stay ahead with the latest science news.