An American spy satellite which had been "lost" for 25 years has finally been rediscovered after decades off-radar in Earth's orbit.

The S73-7 probe had been launched in April 1974 as part of the US Air Force's Space Test Program, and had been set to circle above our planet to help calibrate "remote sensing equipment" to monitor the ground below.

S73-7, just over two feet wide and known as the Infra-Red Calibration Balloon, had been launched into space inside a larger satellite - the KH-9 Hexagon - from which it then decoupled once it passed outside the Earth's atmosphere.

The USAF's plan had been for the little probe to inflate while in orbit, but it failed to do so, and was too small to be regularly picked up by Earth-based scanners.

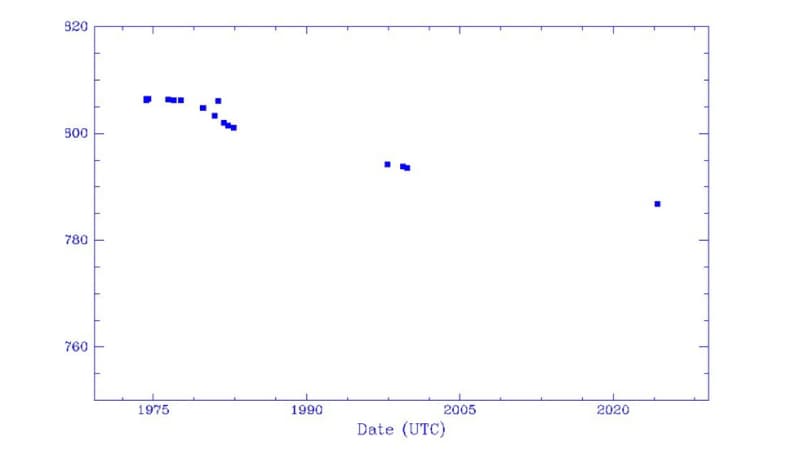

In fact, surveillance teams lost S73-7 twice: first, in the 1980s, then after a few blips in the 1990s, it went off-grid for 25 years.

Tracking personnel from the 18th Space Defense Squadron - now part of the United States Space Force - which keeps watch over all human-made objects in Earth's orbit, had seen nothing of S73-7 for decades.

But now, Squadron analysts have finally locked back on to the mystery probe, prompting praise from astronomer Jonathan McDowell.

McDowell said it was possible the satellite had been "hiding elsewhere in the catalogue as a misidentified debris object"; the probe is small and largely non-metal, which makes detecting it rather difficult.

MORE SPACE MYSTERIES:

The astronomer told Gizmodo: "The problem is that it possibly has a very low radar cross section... And maybe the thing that they're tracking is a dispenser or a piece of the balloon that didn't deploy right, so it's not metal and doesn't show up well on radar."

McDowell pointed to the prevalence of "space junk" - debris in the Earth's orbit - as a reason why scientists may not have been able to find S73-7.

While sensors can detect an object in space, it has to be matched with a satellite known to be on a certain path before it can properly be tracked.

He said: "If you've got a recent orbital data set, and there's not too many things that are similar orbit, it's probably an easy match.

"But if it's a very crowded bit of parameter space, and you haven't seen it for a while, then it's not so easy to match up."

Space debris is a growing problem as more and more nations and organisations attempt to send probes or spacecraft out into the void - the United Nations University think tank has warned that if too many get lost, the risk of collisions and excess debris can only increase.

Debris in Earth's orbit can move as quickly as 17,500 miles per hour, while current estimates suggest that one man-made object drops out of orbit every single day.

Thankfully, collisions are rare - but when two Russian satellites, one of which was defunct, crashed into each other in 2009, the collision created thousands of small pieces of "space junk".