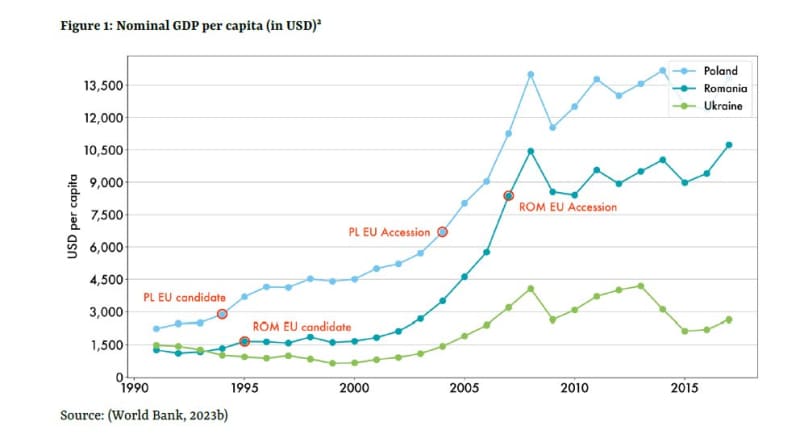

After 20 years in the EU, a comparison of Poland and Romania with Ukraine, which is waiting to join, highlights the prosperity it brings its newest members.

The most obvious difference is rapid growth in wealth of the populations in nominal GDP per capita terms. Both Poland and Romania swiftly reduced the state's share in the economy to below 50% after joining in 2003, says Brussels-based Bruegel think-tank economist Georg Zachmann. Ukraine saw some improvement during the boom years of the noughties, but incomes have been more or less stagnant since then.

Nominal GDP per capita of new EU countries rises quickly

Another change is the improvement in the balance of payments as accession countries invest into production and start to move up the value-added chain. After an initial negative trade balance following accession, membership allowed both countries to invest and consume concurrently. However, this phase of 'borrowing to invest' eventually transitioned for Poland into a net-exporter status, indicative of its economic maturation.

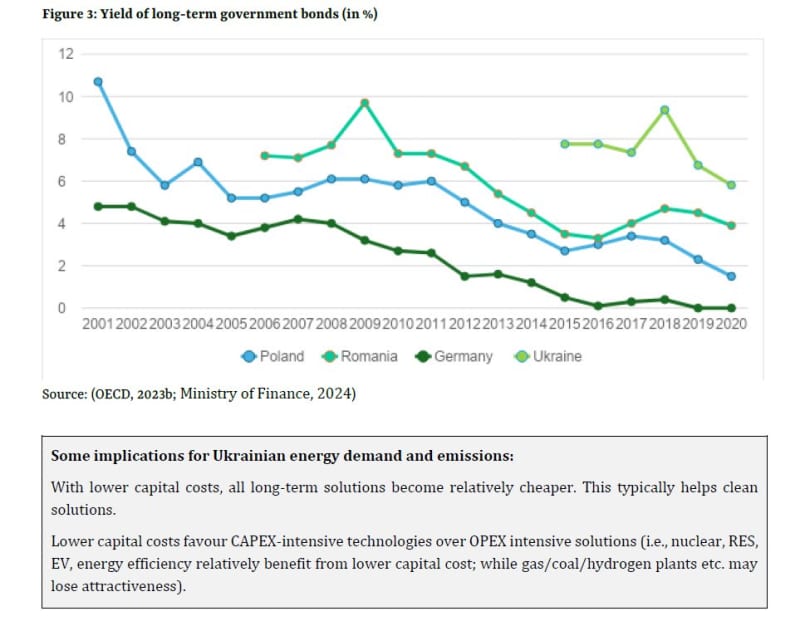

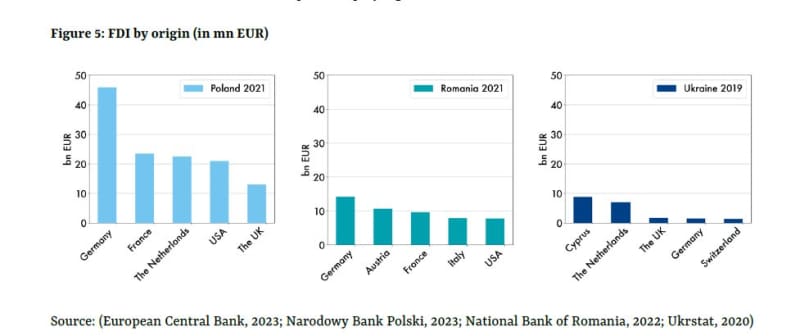

“The first phase of the accession process coincided (likely contributed to) macroeconomic stabilisation - significantly lowering capital cost,” says Zachmann. “Substantial FDI inflows into PL and RO were not just 'hot money' or from off-shore locations (as largely in the case of UA) – leading to know-how transfer and higher overall investment-rates.”

Membership of the EU led to a convergence of bond rates as the poorer members of the Union, like Poland and Romania, benefited from the solid reputation of the strong members like Germany. The upshot was the cost of borrowing fell, giving poor members a boost. However, some countries, like Greece, overdid it, ending in a crisis and an expensive bailout.

Yields of bonds of new members converge to lower rates

FDI surged into new EU members

By contrast, borrowing costs of Ukraine remain punishingly high and have led to rising external debt that is now approaching 100% of GDP.

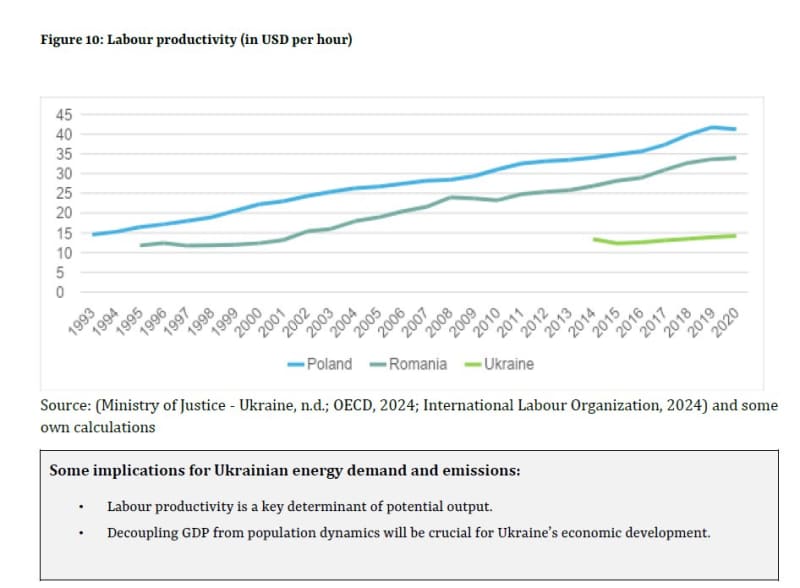

Labour productivity gains is another huge advantage from EU membership. “Productivity surged during and after EU accession for both nations, leading to substantial increases in wages, a development crucial for enhancing living standards,” Zachmann said.

Investment and rising wages lead to improved labour productivity

Poland and Romania quickly brought the share of state-owned companies in the economy to below 50% and there was a notable decline in the share of agriculture in value added, coupled with a rise in the services sector. Particularly striking in both companies was the surge in machinery exports, underscoring a shift towards higher value-added production. Conversely privatisation in Ukraine has gone slowly and if anything it has gone backwards as agriculture has increased its share of GDP.

As Poland and Romania experienced increasing incomes, household consumption patterns evolved, reflected in greater apartment floor-space per capita and increased car ownership, leading to a surge in household energy consumption.

“Increasing incomes in PL and RO substantially increased the apartment floor-space per capita and the car ownership – implying higher household energy consumption,” says Zachmann.

As the process unfolded, the economy became more efficient as owners sought to increase their margins and capitalise on rising productivity by concurrently cutting costs. Energy efficiency within sectors played a pivotal role in reducing energy consumption per unit of output and allowing the revitalised firms to grow even faster.

Overall, the structural shifts observed in PL and RO offer valuable insights for Ukraine, especially regarding mitigating energy demand increases associated with economic growth and addressing the rising household energy demand. As Ukraine navigates its economic trajectory, these lessons from its Eastern European counterparts may prove instrumental in shaping its future policies and strategies.