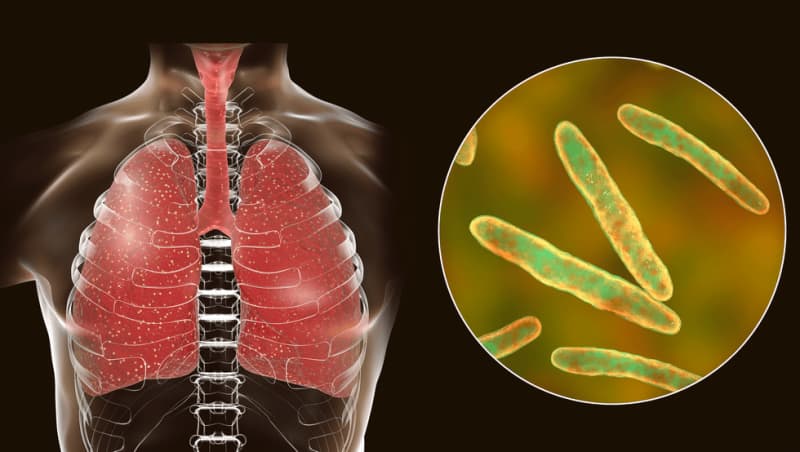

On March 24, 1882, Doctor Robert Koch announced to the Berlin Physiological Society that he had discovered Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacteria that causes tuberculosis (TB).

During this time, TB killed one out of every seven people living in the United States and Europe.

Doctor Koch's discovery paved the way for diagnosing and treating a deadly disease that had plagued humanity for thousands of years.

However, global efforts have stopped short of eradicating TB and it remains one of the world’s deadliest infectious killers.

Despite being treatable with antibiotics, 1.5 million people die from TB each year, which is an average of 2.5 deaths per minute.

It is the leading cause of death of people with HIV and also a major contributor to antimicrobial resistance.

And it is on the rise in England.

The latest provisional data from UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) shows that:

- TB notifications increased by 7.5 percent in the first quarter of 2024, compared with the same quarter in 2023

- There was an 11.2 percent rise in TB notifications in the updated 2023 figures compared with 2022, rebounding to above the pre-COVID-19 pandemic numbers in 2019.

- Increases in TB notifications in quarter one, 2024 compared with quarter one, 2023 were unevenly distributed across regions in England.

Commenting on the data, a spokesperson for the UKHSA told GB News: "The proportion of TB notifications accounted for by people born outside the UK has been steadily rising for a number of years.

"However, the increase in TB in 2023 has now been seen in both UK born and non-UK born populations in England. The largest rises in cases have been in the urban centres of London, the North West and West Midlands. However, there has also been increases in the South West and North East regions where TB incidence is low.

"Tuberculosis continues to be associated with deprivation and is more common in large urban areas. People born outside the UK, especially in countries in South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh), Africa (Eritrea, Nigeria) and Eastern Europe (Romania) experience the highest number of cases. For those born in the UK, TB is more common among those who experience homelessness, drug and alcohol dependence and have had contact with the criminal justice system. TB rates are much higher in UK born individuals from ethnic groups other than white."

How do these statistics translate into risk?

It's important to understand that rates of TB in the UK are relatively low, notes the UKHSA spokesperson.

Or as Helen McShane, Professor of Vaccinology at the University of Oxford puts it, "we still fall well within the World Health Organization's (WHO) definition of a low incidence country".

The figures nonetheless show that "TB is wrestling its way back in the number one slot of killing more people than any other infectious disease" and this should serve as a "wake-up call", the prof tells GB News.

TB can be deadly if it's not diagnosed early and treated promptly with the right combination of specific antibiotics.

The professor is calling on public health officials and the media to promote awareness of TB so that people are diagnosed as quickly as possible.

TB most often affects the lungs. It is spread through the air when people with lung TB cough, sneeze or spit. A person needs to inhale only a few germs to become infected.

According to Professor McShane, TB is driven by social factors: it is a "disease of overcrowding, deprivation and malnutrition".

Given that it disproportionally affects people on the lower rung of the social ladder, "we must try and mitigate those risk factors in people and diagnose TB as quickly as possible", she says.

Closer to home

If TB still seems like a distant threat, a mother-of-three's first-hand account will disabuse you of this notion.

In 2009 Marie Jones had a chesty cough and shortness of breath that she "couldn’t shift". The 42-year-old from Belfast was moving house with her three young children at the time.

"It was incredibly busy with work and moving and sorting out things for my mum who had been diagnosed with early dementia," she told GB News.

She revealed: "I had incredible energy but I started to feel like my bones were weary and still had a bit of a cough - nothing major just felt like I had a cold. This pretty much dragged on from January to September."

In September of that year, Marie thought she had contracted flu as she had had sore joints, cough, a "horrendous" pain in her back and chest so she went to the GP.

"I also had the most awful night sweats and noticed that I had lost a fair bit of weight," she revealed.

Marie's GP sent her for a chest X-ray, gave her antibiotics and steroids which did help.

"As soon as I finished the steroids I was exhausted again and started to notice even a small walk exhausted me," she said.

The mother-of-three continued: "My GP which came back and he said the dreaded word ’shadow’ on lungs and suggested further investigation and I thought I had lung cancer.

"I was asked to do a sputum test which I did and this came back with the diagnosis of TB. I was immediately admitted to hospital and put into isolation. I don’t think I realised how ill I was until I was admitted. I was four stone 13 and my body was bone weary with the racking cough.

"They [doctors] had to find out the ’type’ of TB I had e.g. sensitive or drug resistant and luckily I had sensitive.

"It took a long time to get better from the October to the March and there were days I could barely stand and walk. The night sweats, the cough the back and lung pain were all horrendous and I felt like my body was just wasting away."

How does she reflect on that period now?

"I think the main thing about TB was the length of time I had it and how I just thought it was a cough or a cold and I must have been highly infectious. The worst part was the night sweats - I would be up all night as I couldn’t sleep and the feeling of flu constantly. The sore joints, teeth, and a tiredness that felt it was eating me up from within."

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

Zooming out

The global picture is even more concerning. The rise of TB cases used to be confined to low and middle-income countries but this is no longer the case.

Take America. All but 10 US states have reported rises in both TB cases and rates of infection in the post-pandemic period.

A public health emergency was declared in southern California last month after one person died and nine others were hospitalised due to a TB outbreak.

The number of cases in 2023 shot up by 15 percent in that state alone compared with the previous year.

What explains this rise?

"This is likely due to multiple reasons, but may be related to disruptions in access to healthcare during the pandemic, TB public health programs being stretched thin both during and after the pandemic, and changes to the population demographics," explained Teresa Austin Karre of the College of American Pathologists.

Professor McShane of the University of Oxford agrees that the jump in figures partly reflects a rebound in access to the diagnosis and treatment of TB following serious setbacks during the pandemic.

Viewed in this light, the rise in figures can be seen as a step in the right direction.

However, progress is still far short of meeting the WHO’s 2025 targets of 50 percent reduction in incidence and 75 percent reduction in mortality from TB.

In Ms Karre's estimation, new innovations to diagnose and treat TB have lagged behind due to lack of funding and research.

"The greatest burden of TB, especially drug-resistant TB occurs in areas of the world where there are significant barriers to healthcare access, meaning that cases often go untreated, and spread continues among vulnerable populations," the infectious disease expert lamented.

Green shoots

Despite the current trend, there are reasons to be optimistic.

A Phase 3 clinical trial is currently underway to assess the efficacy of a potential new TB vaccine, with first doses given in South Africa, where TB takes a heavy toll.

Alex Pym, Director of Infectious Disease at Wellcome, which is supporting the trial said: “While it is a long journey to results, the start of this trial in South Africa brings us a critical step closer to having an effective vaccine to protect those most at risk of TB. Global collaboration with regulators, in-country decision makers and communities affected is crucial if those who need it most are to benefit from this vaccine, should the trial be successful.”

The only available TB vaccine, BCG, dates back to 1921. It protects babies and young children against severe forms of TB, but it offers inadequate protection for adolescents and adults against the pulmonary form of the disease, which is primarily responsible for transmission of the TB bacterium.

In GSK’s Phase 2 trial, the M72/AS01E vaccine candidate provided approximately 50 percent protection against progression to active pulmonary tuberculosis for three years in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected HIV-negative adults, which was unprecedented in decades of TB vaccine research.

The WHO estimates that over a 25-year time span, that level of protection could save 8.5 million lives, prevent 76 million new TB cases and save £32.5 billion for TB affected households.

In March, a new way to classify TB that aims to improve focus on the early stages of the disease was presented by an international team involving researchers at UCL.

The new framework, published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, seeks to replace the approach of the last half century of defining TB as either active (i.e., causing illness and potentially infectious to others) or latent (being infected with the bacterium that causes TB [M tuberculosis] but feeling well and not infectious to others) – an approach researchers say is limiting progress in eradicating the disease.

Of note, large surveys conducted in over 20 countries recently have shown than many people with infectious TB feel well.

Under the new classification, there are four disease states: clinical (with symptoms) and subclinical (without symptoms), with each of these classed as either infectious or non-infectious. The fifth state is M. tuberculosis infection that has not progressed to disease – that is, M tuberculosis may be present in the body and alive, but there are no signs of the disease that are visible to the naked eye, for example with imaging.

The researchers say they hope the International Consensus for Early TB (ICE-TB) framework, developed by a diverse group of 64 experts, will help lead to better diagnosis and treatment of the early stages of TB which have historically been overlooked in research.

What's more, a new blood test that could identify millions of people who unknowingly spread tuberculosis could be developed soon, scientists say.

Researchers at the University of Southampton discovered a group of biological markers that are high among infectious patients – and the test could be a significant step in reducing the spread of the disease.

These initiatives are music to Professor McShane's ears but she urges the world to not take its foot off the gas.

"Increased funding and effective vaccination is what's needed if we are ultimately to control this infectious disease and confine it to the history books," she said.