Hong Kong’s justice minister ended a five-day visit to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on Thursday, as the city seeks to enhance ties with the two Middle Eastern countries.

Secretary for Justice Paul Lam arrived in Riyadh on Sunday alongside government representatives – including those from the Department of Justice, Invest Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Trade Development Council, and the Dubai Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office – and figures from the private legal sector.

The purpose of the trip was “to promote Hong Kong’s legal and dispute resolution services,” according to a statement from the Department of Justice.

Speaking at a lunch and network reception that positioned Hong Kong as “the common law gateway for Saudi Arabia businesses to China and beyond” on Sunday, Lam discussed Hong Kong’s colonial history. “Now, the important thing is that during this period of British rule, the British introduced the common law system to Hong Kong and that common law system developing for a century has become extremely reputable and well-established,” Lam said.

He explained why the city’s common law system remained significant, highlighting the overseas judges who sit part-time in the Court of Final Appeal, strict financial sector regulations, a business-friendly legal sector, and the “mutual legal assistance arrangements” that connected the jurisdictions of Hong Kong and mainland China.

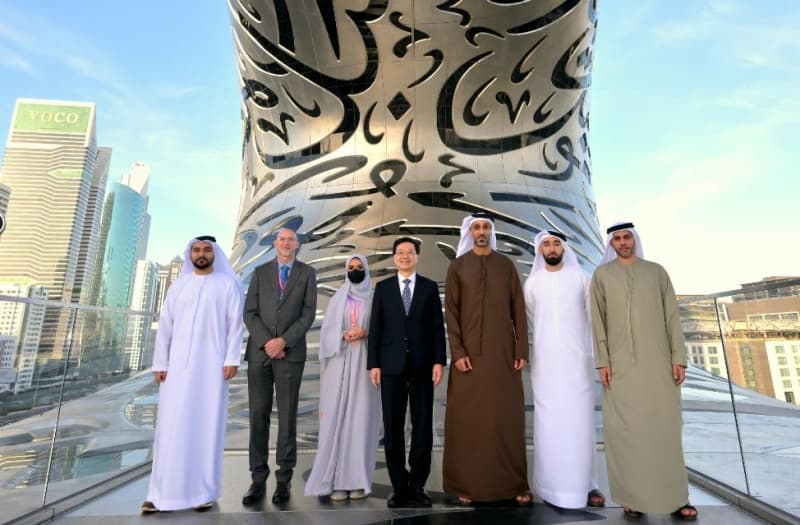

Lam also met Saudi Arabia’s Vice-Minister of Justice Najem bin Abdullah al-Zaid, before moving on to the UAE, where the Hong Kong delegation visited the Louvre Abu Dhabi on Tuesday. They later met representatives of HSBC, Middle East to learn about the UAE financial sector’s demand for legal services.

On Wednesday, Lam hosted a networking lunch in Dubai, again presenting Hong Kong as a common law gateway. He touted the city’s legal system as: “stable, trustworthy, business-friendly, secure and it provides good connections to China and beyond.”

Lam’s visit followed one made by Chief Executive John Lee last February, which the city’s leader described as “fruitful,” and came as Hong Kong sought to tap into the wealthy Middle East market amid tensions between China and the US.

Deputy Secretary for Justice Horace Cheung, who joined Lee’s 2023 trip, said at the time that Middle Eastern political and business figures did not raise questions about a security law imposed on the city by Beijing in 2020, as they were not easily affected by “inaccurate or incorrect information.”

Following the enactment of Beijing’s security law, and further security legislation passed by the city’s legislature in March, some foreign governments – including the US and the UK – have warned of possible negative implications for their nationals living and working in, or even visiting, Hong Kong.

According to the Human Rights Measurement Initiative, which tracks people’s quality of life, safety from the state, and ability to exercise their civil and political rights in countries across the world, Saudi Arabia performed worse than average on all counts, with a poor record on torture, execution, extrajudicial killing, disappearances, arbitrary arrest and the death penalty.

NGO Amnesty International said in 2021 that the UAE commits serious rights violations “including arbitrary detention, cruel and inhuman treatment of detainees, suppression of freedom of expression, and violation of the right to privacy.”

Beijing inserted national security legislation directly into Hong Kong’s mini-constitution in June 2020 following a year of pro-democracy protests and unrest. It criminalised subversion, secession, collusion with foreign forces and terrorist acts – broadly defined to include disruption to transport and other infrastructure. The move gave police sweeping new powers and led to hundreds of arrests amid new legal precedents, while dozens of civil society groups disappeared. The authorities say it restored stability and peace to the city, rejecting criticism from trade partners, the UN and NGOs.

Separate to the 2020 Beijing-enacted security law, the homegrown Safeguarding National Security Ordinance targets treason, insurrection, sabotage, external interference, sedition, theft of state secrets and espionage. It allows for pre-charge detention of to up to 16 days, and suspects’ access to lawyers may be restricted, with penalties involving up to life in prison. Article 23 was shelved in 2003 amid mass protests, remaining taboo for years. But, on March 23, 2024, it was enacted having been fast-tracked and unanimously approved at the city’s opposition-free legislature.

The law has been criticised by rights NGOs, Western states and the UN as vague, broad and “regressive.” Authorities, however, cited perceived foreign interference and a constitutional duty to “close loopholes” after the 2019 protests and unrest.

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team