A landscape from Gaza before the war. Photo by Dana Bsaiso, used with permission.

This story, written by Dana Bsaiso was initially published by We Are Not Numbers on May 15, 2024, as a personal narrative amid the relentless bombardment *f Gaza by Israel\. The story stands unedited, presented as the unfiltered testimony of a war witness, and has been published as part of a content-sharing agreement with Global Voices.*

It is commonly known that grief has five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. You could experience the five stages all in one day, or it may take you months, if not years, to move from one stage to the next.

When grief became my long-term companion after my father, Salem, passed away in December 2020, I thought this was the biggest hardship I would have to endure.

I was oblivious to what was to come. I never imagined that I would have to grieve my entire life as well.

The list of people and things to grieve is getting longer. I now come to grieve for my father, my friend Mohammed Zaher Hamo, my abandoned home, my deserted city, and myself.

I mourn 14 kilometers

Fourteen kilometers.

During my displacement days in the Nuseirat Refugee Camp in Central Gaza Strip, the distance between me and my home in Gaza City was only 14 kilometers. I regularly checked up on the distance keeping me away from home. Each time, Google Maps stated that it was 14 kilometers. I longed for the day that, when I looked up the location of my house on Google Maps, the blue dot would show I was already there.

Since October 13, 2023, Displacement Day, I have slept every night on the thin cotton mattress on the floor, dreaming of myself in my room, sleeping on my comfortable bed.

I dreamt of enclosing the 14 kilometers and making it zero kilometers.

The writer’s bedroom at home in Gaza City, with the crimson duvet, embroidered paintings on the wall, and dazzling twinkle lights. Photo by Dana Besaiso, used with permission.

I longed for my bed, my crimson duvet, my embroidered paintings hanging on the wall, and the dazzling twinkling lanterns that lit up my room at night.

I questioned what happened to the laundry still drying on the wash rack since October 12; did it fall to the ground with the force of the Israeli bombings nearby and now needs another wash? Has the food in the refrigerator become rotten since there was no electricity?

What transpired to the water bottles that my sister, Lama, and I had filled — after Israeli Minister of Defense Yoav Gallant announced a complete siege on Gaza on October 9: “I have ordered a complete siege on the Gaza Strip. There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed” — did someone quench their thirst with it?

“We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly,” Gallant declared. Don’t animals need food and water, as well?

Whenever these overwrought questions crossed my mind, I immediately shut down my brain. Deep down, I didn’t want to know; I wanted home — at least in my mind — to stay the way I left it.

There was no time to grieve.

As a coping mechanism, I had to repress any feelings or thoughts to be able to survive.

On November 24 of last year, I received the news of the martyrdom by Israeli warplanes of my friend Mohammed Hamo. Despite the shocking nature of the news, I did not shed a single tear.

I had to deny such strong feelings of loss to survive. I had to remind myself of Mohammed’s light-hearted jokes that he always used to text me during the genocide to feel that he was still here.

373 kilometers

Recently I was fortunate enough to be able to evacuate Gaza to Egypt along with my family. Nonetheless, this evacuation felt bittersweet.

Al-hamdulilah (thank God), I am no longer exposed to the shelling gunboats, carpet bombing warplanes, and destructive tanks; however, I am extremely homesick.

The writer’s home street before the genocide. Photo by Dana Besaiso, used with permission.

Now, 373 kilometers stand between me and my house.

Now, I have to mourn 373 kilometers.

While waiting for the distance to shrink, it became bigger.

During my time in Nuseirat, the Israeli tanks that wreaked havoc in the Netzarim area, Northern Gaza Strip, served as a barrier. Currently, the list of barriers has grown.

To get home now requires a long car ride to the Rafah crossing, time spent at the Rafah crossing border, an hour to the newly established Israeli checkpoint at Netzarim, and then 20 minutes.

This trip is not possible, though, as Gazans are forbidden to return to the northern part of the Gaza Strip. If they do, Israeli soldiers will shoot at them and kill them.

Imagine being forbidden from going to your home. Finally weeping

The sheer amount of emotion that erupted after reaching Egypt shocked me. Despite being a former friend with grief, I was not prepared for it.

The writer’s home street, now deserted, taken during the ongoing genocide. Photo by Fatma Hassona, used with permission.

One day, while chatting on WhatsApp with a group of friends, one of them sent a sticker that Mohammed loved, along with the words: “Mohammed’s sticker. Allah yerhamo (May he rest in peace).”

It struck me — at that moment — that Mohammed was no longer here, and I wept.

I wept for Mohammed, for myself, for my abandoned home, and for all the people I have lost.

When I think about Mohammed now, a quote by John Green always comes to mind: “Some infinities are simply bigger than other infinities.” Mohammed, a beacon of hope, gave us, all of his friends, forever within the numbered days he spent with us. And for that, I am eternally grateful.

My street back home has turned gray

One night, I was scrolling through Instagram stories, checking the latest updates about Gaza, when a photographer who remained in the north of Gaza shared a video of my home street.

I couldn’t recognize it at first. The street was pale; it all turned gray because of the wreckage and debris.

My heart ached at the scene.

Not imagining that what was once the most vibrant, lively, and energetic area turned into dust and ashes.

How did the blue sea turn gray? How did the air suffocate? How did my entire life suddenly become wrinkly?

I wept at the images. If the street was in such a mess, what had happened to the remaining houses? To my house?

Has my crimson duvet gone gray? Or is it still crimson, the way I remember it?

I miss home. I miss everything it has and everything it represents. As they say, “Home is home.” Whether that home is a hut or villa, the sense of belongingness to the place makes it home.

Gaza City was my home. And I miss home terribly.

A way home will be found

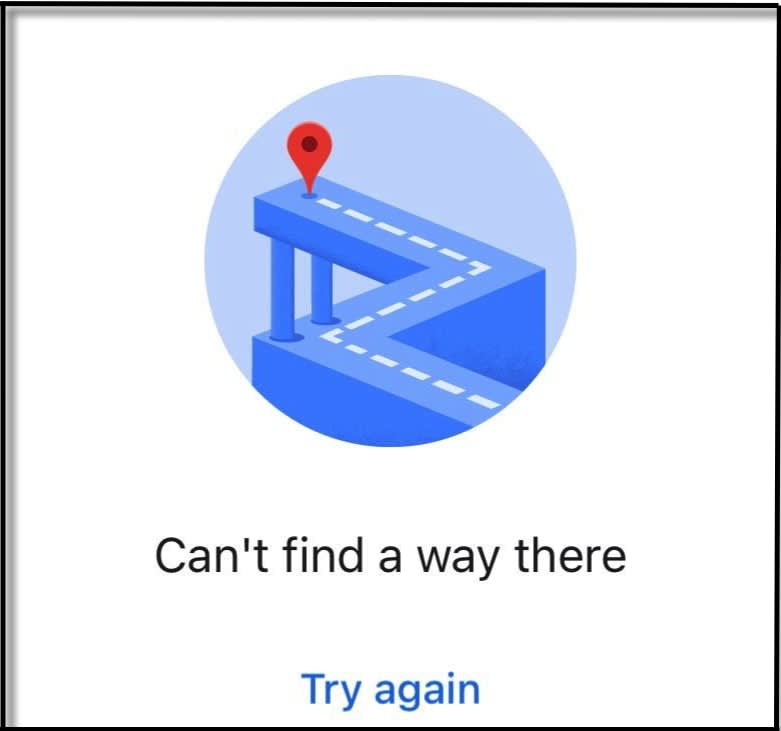

Screenshot of writer’s phone. Photo by Dana Besaiso, used with permission.

Now, after more than 200 days, what would it be like to go home?

Now, Google Maps tells me whenever I look up my house that it can’t find a way there, but I am confident that sooner rather than later a way will be found.

I think — no, I know that the 373 kilometers will disappear, all of the barriers and checkpoints will fade — just like the Israeli occupation will — and I will go back home.

Written by We Are Not Numbers

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.