By Ben Aris in Berlin

The Russian economy experienced a sharp contraction of 4.4% following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, triggering fears of a financial crisis as households rushed to withdraw cash and the ruble plummeted over 40% in value.

The crisis didn’t happen. A swift policy response by the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) and Ministry of Finance (MinFin), including a massive interest rate hike to 20% and the rapid introduction of capital controls in the first week of the war, stabilised financial markets, shored up the tanking ruble and sparked economic recovery within a few months, analysts Yuriy Gorodnichenko, professor of Economics at University Of California, Iikka Korhonen , head of the Bank of Finland institute for Emerging Economies (BOFIT), and Elina Ribakova, non-resident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics wrote in a paper for Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) on May 24.

Since then, the recovery has been bolstered by massive public spending, as the new Putinomics reverses the decade long policy of hording cash and under investing in industry. Money has been poured into the economy, initially in construction and later in military procurement. Mortgage subsidies, designed to hold up economic growth, have also driven housing construction, contributing to the rebound. And despite the inevitable high inflation that is result of all this spending, the lack of labour caused by draining away men to fight in Ukraine, has sunk unemployment to historically low levels of under 3% that in turn has pushed up nominal wages far faster than inflation has eaten into them; the result has been real incomes are growing at their strongest pace in years, feeding a consumption boom that is also driving both growth and tax revenues from the non-oil section of the economy. MinFin earned twice as much tax revenues in the first quarter of this year than it did from oil export receipts.

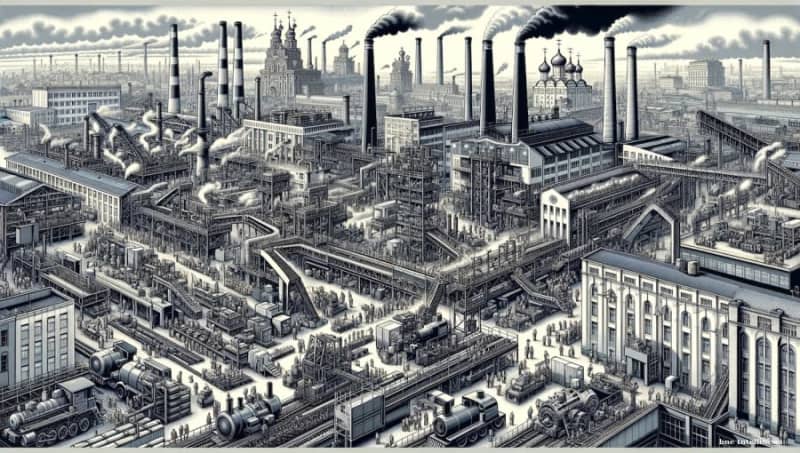

But Russia remains a war economy. Production in war-related industries has surged by approximately 60% in spring 2024 compared to autumn 2022, while other manufacturing sectors remained flat.

From 2021 to 2023, the value-added of economic sectors significantly increased in public administration (including the military), construction (including infrastructure investments in the Russian Far East to serve the Chinese market), and manufacturing (particularly in war-related subsectors such as the manufacture of fabricated metals and 'other vehicles'). Technology sanctions have failed allowing Russia to procure necessary components it needs to keep industry running with some exceptions such as in the LNG industry, and at a much higher cost.

The geographical structure of production and incomes has changed too. Regions with manufacturing in war-related industries have benefited, and so have poorer regions that have sent many men to the frontlines. Soaring Russian household bank deposits have grown fastest in the regions where military recruitment has been more widespread, according to a recent study.

While higher public spending has underpinned much of the growth in recorded GDP, Russia’s federal government deficits have remained relatively small, at approximately 2% of GDP in 2022 and 2023, while revenues from oil exports have been constantly rising and were up over 80% in the first quarter of this year.

“In short, available data show that the Russian economy is progressively becoming militarised. Economic activity is dominated by increased government spending and supported by high revenues from energy exports,” the analysts said.

The structure of the economy has also changed as more and more resources have been poured into the war effort by the Kremlin. Military spending has more than doubled from the $60bn budgeted pre-war in 2021 to the $140bn slated for spending this year.

Russia’s poorest regions have been the biggest winners from the new war-oriented economy. Together with the rising bank deposits in the recruitment hinterland, these two effects are ironically acting to undo some of the income inequality that has marred Russia’s economy and its uneven petro-development since the fall of the USSR in 1991. Most of the standard of living gains over the last two decades have accrued to the so called millionki, or dozen cities with over one million residents, while the rest of the country remains mired in a low income trade and suffer from the lack of modern services.

“In some of Russia’s poorest regions the war has offered many people upward social mobility that was not available in the preceding decades of Russia’s reintegration into global economy,” the analysts say.

Nevertheless, most of these gains have already been exhausted in 2023 and the economy is approximately at full capacity with capacity utilisation running at an all-time high of just over 80%. The process of quick and relatively cheap gains from retooling civilian production and converting it to military production have been completed so adding new capacity will require large and slow moving heavy fixed investment.

“Further increases in military production will likely to be met with high inflation or further decreases of the civilian economy. Moreover, uneven growth across sectors and regions due to exploding military spending creates distortions not only for the current economy but also for future dynamics,” says the analysts.

Have the sanctions on Russia designed to rob the Kremlin of income failed? The analysts argue they haven’t, but admit that they have achieved what they could “considering their limited nature, a macroeconomic environment supportive to Russia for an extended period, authorities’ preparations in recent years and their policy response, as well as support for Russia from countries outside of the sanctions coalition.”

Given the loopholes and exemptions built into the thirteen rounds of sanctions on Russia there has been ample space to find workarounds and exploit the exemption to allow Russia’s economy to function at close to normal. For instance, as no decision had been made to stop trade with Russia and Europe remained dependent on Russian energy, it was necessary to leave certain channels for cross-border transactions open. Gazprombank, one of Russia’s largest banks, and Raiffeisen Bank, a large Austrian bank, are exempted from sanctions. “Not surprisingly, the Russian financial system has been able to adapt,” say the analysts.

Up-coming problems

Russia’s economy is currently the fastest growing of all major economies in the world, but it also faces several major challenges and it will struggle to keep this growth up in the long-term. Amongst its main headaches are: persistent high inflation, restricted labour pool, the increasing unwillingness of domestic banks to buy the state treasury bills, more effective sanctions targeting Russia’s so-called shadow fleet, and restricted access to the best of Western technology that will further lower already falling productivity.

“Labour is not a likely source of economic growth for Russia for the foreseeable future. The negative demographic trends would be hard to overcome unless there is a radical change in the country. Productivity growth is always a big unknown, but for Russia it seems unlikely to be a major source either. The exodus of high-human-capital workers, increasing government intervention, international isolation, and poor protection of property rights are just some of the factors that weigh on productivity growth,” the analysts say.

“Capital accumulation appears to be the only realistic engine. But this can critically depend on Russia’s ability to finance and direct investment. One can anticipate that Russia will be largely excluded from global capital markets and thus the country will have to rely on internal, mostly government sources to cover investment spending,” say the analysts.

That may be a problem. As bne IntelliNews recently reported, Russia’s domestic bond investors are increasingly unwilling to buy Russian Finance Ministry’s OFZ treasury bills, which are now MinFin’s main source of funding.

Russia’s upside scenarios almost entirely rely on high oil prices, which is never a good bet, especially as the green transition continues.

“The balance of risks is such that one can hardly be optimistic about the long-term outlook for the Russian economy. Our results suggest that long-run economic growth for Russia will be less than 1% per year,” the analysts say.

0524 Russia macro growth scenarios CEPR

What is the way forward for the West? The authors conclude that future trajectory of the Russian economy is influenced primarily by the Russian government's military and economic decisions, oil prices, and global pressure to cease aggression. While Western democracies cannot control the first two factors, they can exert influence through sanctions.

Effective sanctions are those with clear, targeted, and measurable objectives that can be adjusted as needed. Key elements for future sanctions include focusing on energy exports, addressing circumvention by leveraging corporate responsibility, and implementing a structured, model-driven approach to design and enforcement.

Sanctions should aim to restrict Russia's economic stability and integration into the global economy, particularly with support from countries like China.

“We believe that a more structured approach has to be brought to the design and implementation of sanctions. We need a coherent way to connect tools and objectives across disciplines, possibly through a structured model-driven approach,” the authors said.