Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. 2015. Photo by Matt Hewit. License CC BY 2.0.

Last August, Ecuadorians made history by voting to permanently keep over 700 million barrels of crude oil in the ground beneath one of the most biodiverse areas on Earth. This made Ecuador the first country in the world to halt oil exploitation through a referendum.

Ayer Ecuador aprobó dejar bajo tierra para siempre un yacimiento de petróleo que se ubicaba justo en una de las áreas más biodiversas #Yusuní

¿Por qué este resultado?

Acá el Preámbulo de su constituciónhttps://t.co/OqvDZlzRVZ pic.twitter.com/ozz2SRQi2R

— Hernán Silva Bórquez (@silva_her) August 21, 2023

Yesterday Ecuador approved leaving an oil field that was located right in one of the most biodiverse areas underground forever #Yusuní Why this result? Here is the Preamble of its constitution

Despite the pressure from environmental groups and Indigenous communities, Ecuador’s government now plans to ignore the popular vote, initially arguing that the decision is necessary to fund the country's efforts to stop a surge in drug cartel violence. Meanwhile, Sinopec and CEDC, Chinese oil companies that hold several oil drilling contracts in the reserve, have remained silent on the government's decision.

Manuel Bayón Jiménez from YASunidos, an activist group that has fought for more than a decade against the oil drilling in the Ishpingo-Tiputini-Tambococha block of the Yasuní National Park, some 675 square miles of pristine Amazon Rainforest, said this about China's lack of statement.

Las empresas estadounidenses en Ecuador siempre han tenido declaraciones con intenciones de presionar las decisiones del gobierno. Las empresas chinas, no lo hacen de manera pública, no es el mecanismo de China.

Unlike the US companies in Ecuador which have always released statements intending to influence government decisions, it is not China’s manner to speak publicly on these issues. There are no spokespersons or public statements.

The Chinese oil groups, Sinopec and CDEC, usually leave on-the-ground operations and social responsibility to Petroecuador, the national oil company of Ecuador, Jiménez said. “I have not seen a single Chinese worker at the ITT.”

Ecuador's government has awarded four sensitive oil drilling contracts in the ITT block, worth billions of US dollars, to the two companies, which are subsidiaries of the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). The country's long-term debt to China is one of the key reasons driving oil expansion in the ITT block, as it has agreed to pay off the debt via oil shipments until 2025 at least, according to its debt restructuring plan. Under the current plan, they have to cease all activities in the Park within a year regardless of their contractual or operational status.

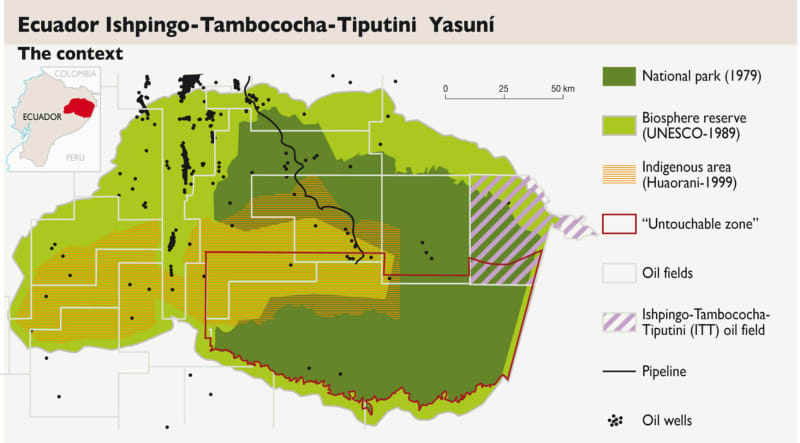

Map of Ecuador's Yasuní National Park and the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini Block, created by GRID-Arendal in 2013. License CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The debt of climate justice

In recent years, China has committed to promoting green energy and to “stop building new coal-fired power projects abroad.” Complying with the result could be a good opportunity for China to gain recognition of its commitment, yet China’s attitude toward the decision is still uncertain.

“Today more than ever, China is at a crossroads: support Ecuador to protect the Yasuní and its ancestral peoples or promote projects that destroy it,” said Latinoamérica Sustentable (LAS), an Ecuador-based organization dedicated to environmental protection in Latin America with a focus on Chinese investments, in a 2023 report urging China to consider its commitment to address climate issues.

In fact, despite China’s ambition to address global warming, more than 80 percent of the financing from Chinese policy banks and half of the loans from Chinese commercial banks directed towards the energy sector in Latin America are predominantly focused on the oil industry.

China's presence in Ecuador's oil industry dates back to the mid-1990s when several Chinese companies entered the sector as subcontractors. Starting around 2008, then-President Rafael Corea signed a series of loan agreements with China, agreeing to exchange the country's oil for Chinese funding. Until now, Ecuador has borrowed more than USD 15 billion from China, making the Andean country the third largest recipient of Chinese financing in the region, behind only Venezuela and Brazil.

A former Ecuadorian leader and manager of Petroecuador both admitted that the contracts with China, all tied to the sale of oil or with crude oil as collateral, were “harmful” to the country.

Ecuador has not only lost its sovereignty in managing its oil independently due to the contract conditions but has also put its diverse ecosystem and social wealth at stake.

Since 2016, seven new oil contracts have been awarded to Sinopec, with four allowing the exploitation of the ITT Block. The most recent one was signed in February 2022 between Petroecuador and CDEC, marking the first instance of a Chinese company operating in the Ishpingo north field. This field is situated just 300 meters from the buffer strip, where two Indigenous tribes — the Tagaeri and Taromenane — reside in voluntary isolation.

The public outrage led more than 60 percent of Ecuadorian voters to choose to stop the development of the ITT block. Before the referendum, it was producing around 57,000 barrels per day and was expected to bring in around USD 14 billion over the next 20 years, according to Petroecuador.

The referendum did not happen without economic rationale. The result doesn’t stop all the oil blocks in the National Yasuní Park, where more than one billion barrels of crude oil are believed to be reserved underground. Chinese oil companies have operated in five other zones in the country.

Additionally, the Ecuadorian government initiated a trust fund from rich countries to stop the exploitation of the ITT park in 2010. However, the initiative failed to gain USD 3.6 billion worth half expected earnings from the potential sale of oil at the time in 2013. Then the government began to negotiate a deal secretly with a Chinese bank, trading drilling access in the ITT block in exchange for Chinese lending.

Activist groups like YASunidos have fought to protect the area over the past ten years. Their activism has gained overwhelming support, to the point that the recently-elected President Daniel Noba used the referendum as one of his campaign promises in the October Presidential Elections.

However, in January, after an armed gang stormed an Ecuador TV station, Noba announced his support for a “moratorium” for at least one year. Other officials and legislators are exploring ways to circumvent the decision of Ecuadorians, citing the country's economic instability.

In the meantime, China has stayed noncommital about the dispute. The Chinese Embassy of Ecuador has not yet made a public comment on the result of the referendum. Sinopec, for example, did not mention Ecuador or the Yasuní Park in its 2023 sustainable report.

Perhaps the only glimpse into China’s attitude from the public came from an article published by the Ministry of Commerce of the PRC a few weeks before the referendum was held. It intentionally quoted Ecuador’s Minister of Energy and Mining, who said that opposing oil and mineral extraction would be tantamount to “suicide” and send a “negative signal” to investors.

Ecuadorian citizens made their country the first in the world to stop oil extraction through a democratic vote. Ecuador is also one of the first nations to recognize nature as a subject of rights in its constitution. Its people will not easily compromise.

YASunidos reiterated that they would take further steps if the government breaks the promise again. If necessary, they would call for the dismissal of ministers and even the president.

“They are already late with removing the infrastructure,” said Jiménez.

Written by Gabriela Mesones Rojo, yingyu.alicia.chen

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.