Nvidia, worth $3.01 trillion (€2.76 trillion) as of Thursday, just took over Apple as the world’s second most valuable company.

The firm’s share price rose more over 60 points, or five per cent, on Wednesday to more than $1,224 (€1,125) per share. Nvidia is just the third company in the world, following Microsoft and Apple, to be valued at the trillion-dollar mark.

Nvidia has been designing semiconductors, or microchips, since 1993; first for video game consoles and now for the generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) companies.

The major question now is can any European companies compete with the meteoric rise of Nvidia?

Who’s who in the booming AI microchip industry

Microchips are the engines that power the world’s biggest tech companies and their AI divisions.

There are five separate types of companies that make up the semiconductor market, according to Cem Dilmegani, principal analyst with consulting company AIMultiple.

At the base of the industry are those that create the machines needed to mass produce microchips, including Dutch company Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography (ASML), which is worth €361.67 billion.

Then, foundry companies like Taiwan’s Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) use these machines to manufacture the chips that other design companies, like Nvidia, will refine for AI models. The biggest global players at this level of the semiconductor industry are located in China, South Korea, and Taiwan.

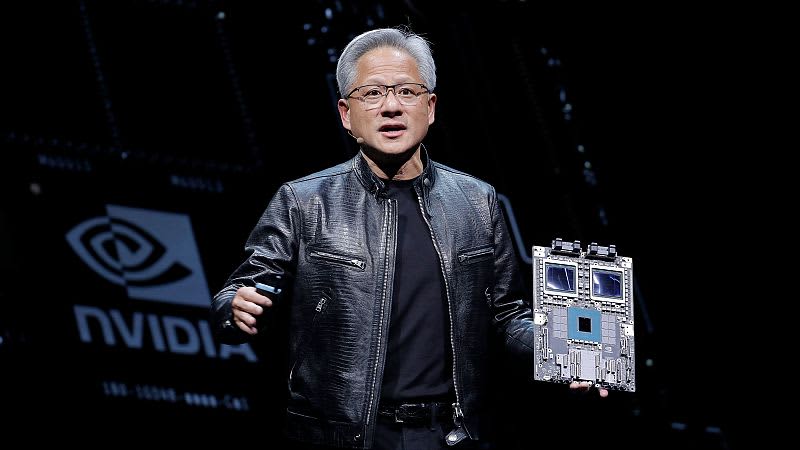

Design companies like Nvidia come next who, according to the company’s website, “engineer the most advanced chips, systems and software for the AI factories of the future”.

Those engineered chips are then bought by the major tech companies - from France’s Mistral AI to Big Tech giants Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft - to programme the large language models (LLMs) that power AI.

Nvidia in particular specialises in graphics processing units (GPU) chips that render higher quality images than the central processing units (CPUs) their American competitors Intel and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) are known for.

These GPUs are able to perform calculations in a way that CPU chips cannot, which means they can better handle the type of work needed by AI companies.

For companies that can get their hands on Nvidia’s chips, it also means they’ll need fewer staff members to train their languages, according to Dilmegani.

“It will require a lot more work and you’ll need to put more engineers on it,” he said. “You might also need more computing time or the [language] model might be running slowly”.

‘We create a whole ecosystem’

Serge Palaric, Vice President of EMEA for Nvidia, joined the company in 2004 when they were still designing GPU chips for video consoles like the Xbox.

Then, by 2006, Nvidia launched Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA), their own programming language for their GPU chips. It’s now a deep learning software companies can buy alongside its engineered chips.

Palaric attributes his company’s rise in the semiconductor market to both the hardware it has designed and the software that simplifies the work of these major tech companies.

“We are not selling chips, we are selling software,” Palaric said. “We create a full ecosystem in order to be able to address and support these enterprises that want to make the move to [generative] AI”.

"ChatGPT was developed over 10,000 GPUs so we knew what was coming. We are always looking at what is the next step, how do we do it, [and] how do we help our partners to do it”.

In 2012, Nvidia and the University of Toronto discovered that GPUs make deep learning - the type of learning that powers today’s AI - more accurate. From there, the race was on within Nvidia to make way for the eventual AI boom.

So, when OpenAI’s ChatGPT took off in 2022, Palaric said Nvidia wasn’t at all surprised and was ready to meet the moment.

“ChatGPT was developed over 10,000 GPUs so we knew what was coming,” Palaric said. “We are always looking at what is the next step, how do we do it, [and] how do we help our partners to do it”.

On June 2, AMD and Intel both announced new AI processors to capture back some of the market share from Nvidia, who controls about 80 per cent of the market for the chip design.

‘Nvidia is in a class of its own’

Based on market share alone, ASML is the biggest player for Europe in the AI semiconductor industry, according to Dilmegani.

But, because Nvidia engineers GPU chips and ASML provides the machines to those that manufacture them, it’s not accurate to equate the dominance of ASML and Nvidia in their respective parts of the industry, according to Michelle Brophy, Director of Research at AlphaSense, an AI-powered market platform.

“None of the Europeans are close to [Nvidia’s market cap] at all,” Brophy told Euronews Next. “They will find their niche areas but Nvidia is in a class of its own”.

In theory, Dilmegani said ASML could scale vertically to start designing its own microchip technology. However, it would be “strange” and “very complex” because it will then compete with other chip manufacturing companies that make up its client base.

Where ASML is competitive, according to Brophy, is to help TSMC improve the manufacturing of its chips. The Taiwanese manufacturer has said publicly that it wants to start making 2-nanometre chips by 2025, offering chips with 10 to 15 per cent faster processing times than the advanced 3-nanometre chips currently on the market.

Brophy said the “only way [TSMC] can get there” is to work with ASML.

Elsewhere, two European companies already design semiconductor chips: Germany’s Infineon and French-Italian STMicroelectronics, Brophy said.

Both companies work on CPU microchips specifically for the automotive industry and have not signaled publicly that they will be taking on Nvidia.

Brophy said it wouldn’t be wise for them to do so.

“They would have a lot of work ahead of them,” Brophy said. “If their next step would be towards AI, it would likely be in the processing side”.

Euronews Next contacted both Infineon and STMicroelectronics but did not receive a response from either company at the time of publication.

‘We are not taking many risks’

If European companies or start-ups want to become competitive in the industry, they need to either develop a niche in a different part of the semiconductor market like ASML, according to Dilmegani and Brophy.

Alternatively, they should develop the necessary relationships so leading chip design companies like Nvidia or AMD consider moving their operations to the continent.

Brophy pointed to a recent deal with Intel in Germany as an example of areas Europe could invest more into.

In 2023, Intel and Germany signed a €30 billion deal to create a microchips factory in Magdeburg, but the deal is still pending approval from the European Union, according to Politico.

“Start-ups need to think about where the technology is going and take bold bets and make machines that are different than other processors. But you need an ecosystem for these companies to emerge… and in the EU, we are not taking [many] risks in that dimension”.

An EU spokesperson told Euronews Next that the bloc can't comment on the progress of this deal.

The goal for companies like Intel to invest in European chip manufacturing plants is to move away from a reliance on TSMC, the biggest chip manufacturer, due to political tensions between the West and China, Brophy said.

Palaric from Nvidia said the company will continue to rely on TSMC for their chips.

What Nvidia is doing in Europe is investing in AI startups like France’s Mistral AI, the UK's Synthesia, and Germany's Northern Data Group’s AI Accelerator.

Their goal, according to Palaric, is to provide the technology it needs for companies to develop their own languages.

Any start-ups looking to design chips like Nvidia, according to Dilmegani, will likely need at least a decade to grow their presence enough to be competitive.

"Start-ups need to think about where the technology is going and take bold bets and make machines that are different than other processors," Dilmegani said.

"But you need an ecosystem for these companies to emerge… and in the EU, we are not taking [many] risks in that dimension".