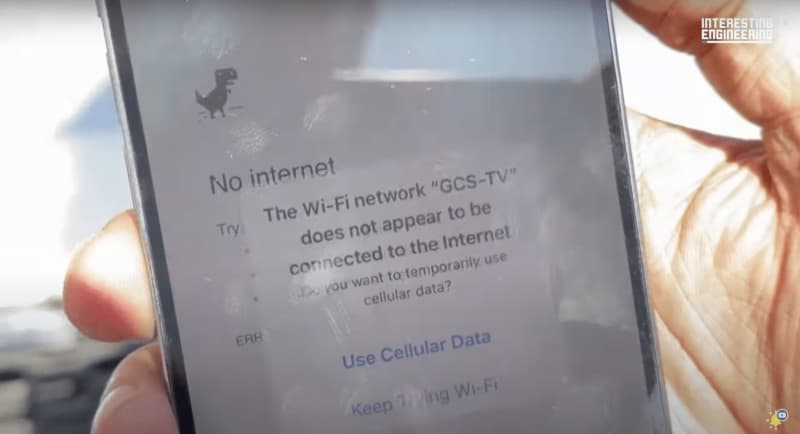

No internet in Gaza. Screenshot from a video “Can Starlink Provide Internet To Gaza?” by Interesting Engineering. Fair use.

When the combination of big tech and politics failed the Palestinian people by overlooking the internet disruptions affecting Gaza, grassroots technology known as the “network tree” came to the rescue. Utilizing the humblest of elements such as buckets, smartphones, and e-SIMs, this ingeniously simple technology provided much-needed connectivity to a community fragmented by war, in the face of severely damaged infrastructure.

Since the war on Gaza began in the aftermath of October 7, the telecommunications infrastructure has been severely damaged, along with critical sectors like education, healthcare, and more. Telecommunications disruption in Gaza has significantly hindered daily interactions and vital operations. Repeated blackouts have intensified Gazzawis isolation. According to the UNRWA’s June 5, 2024 report, it is becoming “increasingly difficult to communicate with humanitarian personnel on the ground.”

This is further exacerbated by direct attacks on civilians attempting to access the internet. According to a report by Euromed Monitor dated May 16, 2024: “The Israeli army continues to repeatedly target and kill Palestinian civilians, including journalists, as they attempt to access communications and Internet services to reach their families or employers.”

Communication disruption has caught the attention of international figures like the acclaimed director Manolo Luppichini. Since 1994, Luppichini has directed several projects, gaining numerous awards. In an April 16, 2024, interview over Zoom with Global Voices, he discussed his recent trip to Rafah aimed at improving internet access, his commitment to the Palestinian cause, and the challenges he faces:

Rafah is just the latest beat in my 25-year closeness and care about the Palestinian issue. I believe if we neglect international issues, particularly those involving war, we fail to see the full picture and are heading rapidly towards a permanent global war.

The Palestinian problem is just the tip of the iceberg, a very visible and significant issue. Just look at what's happening in Ukraine, Sudan, Myanmar, among other countries. The language of war has been subtly yet consistently injected into our global narrative over the last 20 years.

As a filmmaker I traveled to Gaza to make documentaries, so I had the chance to talk to people. I have shared experiences with Gazzawis, who are like brothers to me. It's also quite frightening because during our chats, there's this sense that it might be the last time we speak. It's truly heartbreaking.

Reflecting on the limited impact of filmmaking for social change in the face of the ongoing humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza despite widespread exposure, Luppichini decided to move beyond raising awareness to actively participate in finding solutions with tangible impact:

Lately, I've felt the need to become more involved. Showing films often doesn't lead to change; people watch them, but then, nothing happens. So, I thought that “putting my hand in the metal” and creating something with a direct impact would be more useful.

I have released very powerful videos, I naively thought that my communications could improve the situation. Bullshit, no one cared, nothing changed at all.

This decision drove Luppichini to go to Rafah, where he felt a moral outrage at the apparent disregard for human life.

I was in Egyptian Rafah. We couldn't see much, but could smell the war on the other side of the wall. The situation is beyond shameful; having people starve on one side, while the food, water, and medicine is rotting in the heat of the desert in the trucks on the other side.

In Italy, we have a saying: “You shouldn’t shoot at the Red Cross.” It means that some actions are despicable. But now, hospitals are being targeted and people are buried under their ruins in broad daylight, yet, there is no international reaction.

I am shocked, because anyone can claim to have moral authority, but on which moral authority is the USA standing? What is happening is Gaza is making us vulnerable to any consequence. This indifference will enable the worst assholes. Forgive my language!

Communication barriers in Gaza hinder information flow, worsened by a global narrative shaped by colonialism-influenced mainstream media. This narrative often misrepresents the situation on the ground and undermines Gazzawi voices, presenting a skewed perspective.

It is incredibly frustrating dealing with communication blockades, especially for those who understand the reality on the ground. We can’t communicate with our brothers and sisters there.

Back in 2009, while in Gaza, I found myself picking up bomb fragments, analyzing the types of metals used. I had not heard of Dense Inter Metal Explosives (DIME) bombs then, the ones designed to cut the legs. While filming there, I've been shot at several times.

This firsthand experience amplifies my frustration when Western journalists say that they need to go and tell the story in Gaza, as if Gazans can't tell their own stories or share real-time information. This colonialist approach makes me question why patronizing Westerners need to narrate Gaza’s experience instead of recognizing the voices from within? It's a very strange way to interpret press freedom.

Luppichinic decided to tackle the communication problem in Rafah by collaborating with old comrades, who are committed to leveraging their technical skills and experience with early digital activism. They wanted to use grassroots technology to reclaim power in the oppressive situation in Gaza.

I'm part of this group of elderly but active people — you might remember from the media back around the Seattle anti-globalization movement in 1999–2000 and the Indymedia network.

This group of nerds managed to create a community on the internet way before social media platforms were established. So, we began to explore ways to overcome the Israeli blockade of the internet.

Their journey entailed significant challenges related to logistical and bureaucratic obstacles in delivering essential supplies to Gaza.

It was a complete mess. We explored several options, but they all turned out to be disastrous because everything was either expensive or required lengthy permissions from the Egyptian government. It is impossible to import anything through the border.

We were in the warehouse, where the rejected items were stored. It was an incredible scene with items like, solar panels, baby incubators, and oxygen cylinders for hospitals, all rejected. The policy was absurd — if they found even one prohibited item in a truck, they would reject the entire truck, even if everything else was permissible. This made it incredibly difficult to get technical equipment through.

The ‘Network of Web Trees’

Luppicchini partnered with the Associazione di Cooperazione e Solidarietà (ACS), an Italian NGO focused on emergency and sustainable development in global majority countries in collaboration with local communities.

ACS developed the “Network of Web Trees,”a system using the latest generation mobile phones equipped with eSIM technology — virtual SIM cards activated by a code to function as traditional SIM cards. This system, set up as Wi-Fi hotspots that could transmit radio signals across the border, supports up to 50 additional devices, allowing connections to Egyptian or Israeli cellular networks without the need for modern phones. The Web-Trees are grown by local ‘Web-Gardeners.’

We sent the Web-Gardeners money and they managed to buy these items on Gaza's black market. Our technical team outside Gaza worked with the Web-Gardeners inside Gaza, exchanging photos and messages for feedback. It was a collaboration between people from Italy and Gaza.

They found the necessary tools, and we sent them the QR codes via WhatsApp to activate the eSIMs.

Then it magically worked. We were so happy, we were crying. It was so sweet.

However, even the simplest solutions can be dangerous in Gaza.

Ali's “bucket” has become emblematic of how igneous Gazzawi people can be. Photo by Associazione di Cooperazione e Solidarietà ACS. Used with permission.

Open areas near beaches typically have clear reception without obstacles. However, in other regions, to catch a signal from across the border, people have to climb to higher positions like rooftops. This can be dangerous because those bloody drones target anyone they detect.

Ali, the most experienced in the Web-Gardeners team came up with a very funny solution that has become emblematic of how igneous Gazzawi people can be. He created what he calls “the bucket.” Essentially, they place the mobile phone with a power bank inside a bucket and attach it to a pole and raise it like a flag using a rope. This setup allows the phone to connect to and spread the signal from a safer, elevated position without anyone having to physically be up high.

Despite the simplicity of the grassroots communications network, it has been crucial for civilians, who are the real victims of the communication disruptions.

The real impact of internet disruptions is felt by ordinary Gazzawis. They are left without knowledge of what's happening with their neighbors or relatives, potentially just 500 meters away, due to movement restrictions or the risk of being shot.

This grassroots movement is Luppichini and his team’s effort not only to maintain critical social bonds, but also serves as a form of resistance against cultural genocide.

This is simply a grassroots operation that not only connects people to the outside world but also connects people within the community itself. This connection is crucial for maintaining community bonds. It is also one solution in the face of global double standards that mobilized solutions in Ukraine, but failed to do so in Gaza.

Genocide involves not only physical destruction but also cultural erasure, disconnecting people from their cultural and physical references. Thus, keeping Palestinians in Gaza connected among themselves is crucial to combating the ongoing genocide. Maintaining these connections serves as a vital tool to stop the ongoing genocide.

Written by Mariam A.

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.