By Ashley Yeong

Tioman Island Marine Park in Malaysia, renowned for its coral reefs and vibrant marine life, is facing a silent but potent threat: ghost nets.

These lost or abandoned fishing nets are typically made of plastic and could take centuries to break down. In the meantime, they can damage delicate ecosystems and entangle and kill marine wildlife.

Ghost nets are widely studied globally, but local information is scarce. To bridge this knowledge gap, scientists analyzed data from a ghost net removal program on Tioman Island. Their findings, published in April in The Palawan Scientist, found a rising trend of ghost nets in the waters surrounding the island and identified patterns in their origin.

“Ghost nets are a recurring problem on Tioman,” the study’s lead author, Alvin Chelliah, chief program officer at local marine conservation NGO Reef Check Malaysia, told Mongabay by email. “The main difference now is that we have trained local divers that respond quickly whenever a net is reported.”

Numerous fish trapped in a ghost net tangling a coral reef in Tioman Island Marine Park. Video courtesy of Reef Check Malaysia.

In 2015, Reef Check Malaysia started the Tioman Marine Conservation Group (TMCG), a band of local volunteers trained to remove ghost nets from Tioman Island’s reefs and beaches. The NGO also set up a hotline where anyone can report a ghost net sighting. Once the TMCG divers get enough information, they go to sea to start the removal process.

This can be arduous, depending on the net’s size and the extent of the entanglement, and it requires care to prevent further damage to the substrate and any trapped animals. Chelliah recounted an instance when it took seven people half a day to extract an 800-kilogram (1,764-pound) net from a Tioman reef.

“There were also many fish, crabs and a turtle that had gotten tangled and drowned. I won’t forget it because it was extremely difficult to cut from the reef and to lift out of the water,” he said.

A pandemic spike in ghost nets

From 2016-22, the TMCG retrieved a total of 145 ghost nets weighing 21 metric tons from the island’s waters. Analyzing data from these retrievals, the study identified a spike in ghost nets during the COVID-19 pandemic when fisheries were considered essential services. Whereas the team retrieved 8-14 nets annually from 2016-19, the number jumped to 24 in 2020 and to 39 in 2022.

“Many who had lost income due to the movement control borders turned to fishing during this period,” Chelliah said. “But they lacked the skills and knowledge regarding the sea, fishing grounds or how to properly use fishing nets.”

Chelliah’s study found that most of the nets had drifted in from boats fishing illegally inside the marine protected area or legally outside it. He and his co-authors wrote that increased enforcement pressure may prompt illegally fishing boats to hastily abandon their nets to flee from authorities.

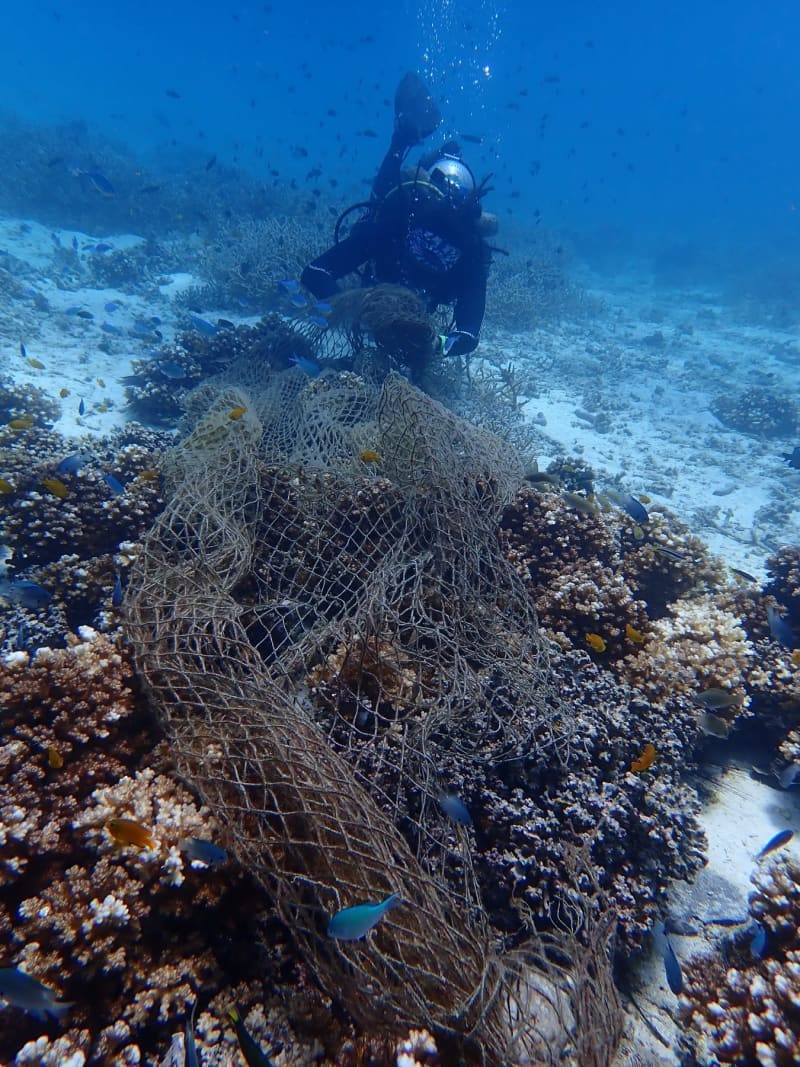

A diver removes a ghost net from Tioman Island Marine Park in Malaysia. Image courtesy of Reef Check Malaysia.

Polluting the ocean, killing wildlife

Coral reefs are particularly vulnerable to ghost nets because in addition to breaking slow-growing corals directly, the nets also block sunlight, which corals rely on to make their food, killing them slowly, Chelliah said.

Ghost nets also trap a variety of marine life, including sea turtles, dolphins, sharks and whales. Smaller animals swim right into the nets, not realizing the danger, while bigger animals can get stuck while trying to feed on the dead animals trapped in the nets.

In January 2023, Chelliah said he received a call about a ghost net. When the TMCG removal team arrived at the site, they found a net tangled on a reef with nine bamboo sharks (Chiloscyllium punctatum) among the animals trapped inside.

“It is sadly common to find sharks tangled on ghost nets as they come to feed off the other marine life that are stuck on the nets,” Chelliah said. “The only positive part to this story is that we were able to set five free and only four had already died. I only wish we arrived sooner.”

This problem is hardly unique to Tioman Island. A 2022 study in Science Advances estimated that every year, 2,963 square kilometers (1,144 square miles) of gillnets, 75,049 km2 (28,976 mi2) of purse seine nets and 218 km2 (84 mi2) of trawl nets are lost to the ocean. The area of these nets is nearly three times that of the state of Hawaii.

Chelliah’s paper noted a number of places with far bigger ghost net problems than Tioman Island: More than 1,600 net panels wash ashore on Turkey’s Black Sea coasts annually, for instance, and 40,000 gillnet pieces appear annually in Sadeng, Indonesia.

A blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) found dead in a ghost net in Tioman Island Marine Park. Sharks often get entangled in ghost nets when they approach to feed on other marine life trapped there. Image courtesy of Reef Check Malaysia.

Tighter rules on fishing nets needed

For an island community where three-quarters of the 3,500 residents rely on tourism as their main source of income, preserving Tioman’s thriving marine ecosystem is crucial.

“We need to stop these nets from getting in the water in the first place,” Chelliah said. “Most ghost nets found in the sea have been dumped on purpose or lost due to gear malfunction or human error.”

Part of the solution is finding convenient, cost-effective ways for fishers to properly dispose of worn-out nets, he said. Reef Check Malaysia is considering placing bins at fish landing sites on the mainland, 50-60 km (31-37 mi) south of Tioman Island. Chelliah said the buying and selling of fishing nets should also be controlled and enforcement and fines ramped up for illegal fishing.

Abe Woo Sau Pinn, a senior lecturer at the Centre for Marine and Coastal Studies at Universiti Sains Malaysia on Penang Island, expressed similar concerns.

“With the increase of more industrialized fishing and artisanal fishing, more gears will eventually end up becoming ghost nets,” Woo, who was not involved in the study, told Mongabay by email. “It is never surprising to find ghost nets in ecosystems where human is present.”

What is surprising to Woo is the close proximity of these ghost nets to a marine protected area: “Imagine places that are not marine protected areas,” he said.

He noted that differing regulations on net disposal across different countries complicates efforts to prevent ghost nets from polluting Malaysian waters.

“However, the scientific community and NGOs should continue to advocate for … relevant laws and push for governments to commit towards combating ghost nets,” Woo said. “Ghost nets are not degradable therefore prioritizing removal is very important to keep damages to resources and ecosystem minimal.”

People pull a ghost net and other trash onto a boat for proper disposal. Image courtesy of Reef Check Malaysia.

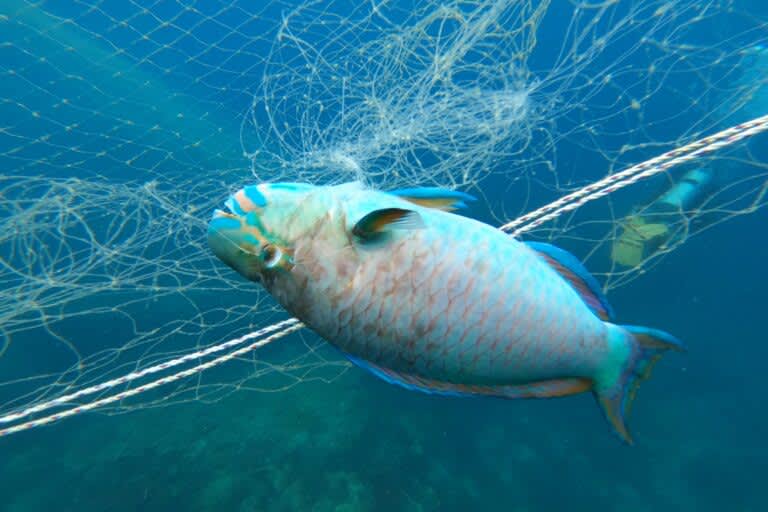

Banner image: A parrotfish (family Scaridae) tangled in a ghost net in Tioman Island Marine Park. Image courtesy of Reef Check Malaysia.

Ashley Yeong is an independent journalist based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. She is interested in topics on climate, biodiversity and conservation, with a special fondness for the ocean. She is a member of the Oxford Climate Journalism Network.

Citations:

Chelliah, A.J., Chen, S.Y., Shahir, Y., and Dolorosa, R.G. (2024). Incidence of ghost nets in the Tioman Island Marine Park of Malaysia. The Palawan Scientist, 16(1), 28-37. www.palawanscientist.org/tps/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/4_Chelliah-et-al-Galley-Proof-Version_1.pdf

Richardson, K., Hardesty, B.D., Vince, J., and Wilcox, C. (2022). Global estimates of fishing gear lost to the ocean each year. Science Advances, 8(41). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq0135

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay