2024 will be remembered as the year of global elections. And so far, it seems determined to live up to that billing, with a series of democratic events that feel hugely consequential for the future direction of our world.

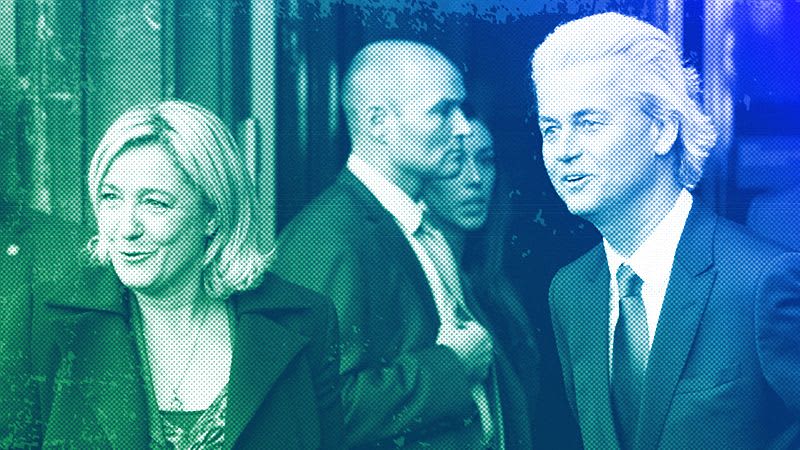

From Germany to France, Italy, the Netherlands, the US and the UK, a key part to this is the rise of a populist, nationalistic, far-right faction.

We simply can’t ignore the fact that these voices are becoming a significant part of the political landscape, although the extent of this varies from country to country.

For instance, the European Parliament elections this week saw clear increases in populist-right parties.

While they remain a relatively minority voice, they could become a threat to the centre-right groupings that have dominated politics over the last decade. That far-right rise can be observed particularly in countries like France and Germany. However, at the same time, Poland and other Nordic countries shifted in the other direction.

In the UK, Nigel Farage of the Reform Party (previously the Brexit Party) is undeniably a populist and feels like an increasingly visible figure, gaining an alarming amount of media attention.

Farage threatens what could be a catastrophic splintering of the governing Conservative Party’s political coalition. While his party is growing in supporters, it is also deeply polarising and unlikely to secure more than a couple of MPs in the upcoming election.

And, of course, the most impressive politician of this ilk is Donald Trump — the man who repeatedly calls climate change “a hoax”. Trump’s potential return to the US presidency this year could be incredibly dangerous.

Most far-right political groups oppose measures to deliver action on climate change and environmental protection as a key part of their platform.

Indeed, some commentators — and some of the politicians leading these groups — have claimed that their support represents a backlash against green commitments. But does this stack up?

Policy failures can cause a backlash

The reality is, poll after poll shows climate action and nature restoration is a priority for people — even as they often do show that, yes, people are concerned about the costs and restrictions that might be imposed on them as part of this agenda.

In places like the UK and the EU, climate policy is increasingly mature, and we have a growing body of evidence about what works and what doesn’t.

In a world where many people are struggling, temperatures are rising, and extreme weather events occur weekly across the globe, it does matter how you deliver on climate commitments.

Whether its agricultural regulations for Dutch farmers, taxing fuel for French rural road users, or deploying a relatively more expensive new technology into German households in the middle of an energy price spike, there are a growing number of green policy missteps.

We have seen numerous successful climate policies that have driven a huge degree of change, like the historic Inflation Reduction Act in the US, but there have been instances of backlash that tend to arise from very specific policy failures.

It’s usually where a group who are feeling overstretched gets hit by a regulation designed to deliver change — but that adds to a burden they already feel is unsustainable.

Whether its agricultural regulations for Dutch farmers, taxing fuel for French rural road users, or deploying a relatively more expensive new technology into German households in the middle of an energy price spike, there are a growing number of green policy missteps.

It’s also possible to take the wrong message from these incidents — opposition to specific policies does not mean that the overall effort to clean up air and water and to deliver climate stability is not well supported — and it can be a political mistake to think otherwise.

Listening to people matters more than you think

Our research has underlined how much it matters that you listen to people and look at the effect of policies they may already be living with. We need a just transition where we bring people with us and pay attention to how they are doing financially.

For example, we at the Cambridge Institute of Sustainability Leadership recently did some research looking into how to best design climate policies that work with our European Corporate Leaders Group.

Transforming our economies has to be a marathon, not a sprint — and we need to include everyone. The very political polarisation that we’re currently seeing will make this harder.

By looking at practices and behaviours around energy, transport and recycling/waste, we were able to analyse what would directly incentivise European households to take climate action.

The state of our climate and the deeply worrying collapse in natural systems we all rely on require us to act with urgency.

But transforming our economies has to be a marathon, not a sprint — and we need to include everyone. The very political polarisation that we’re currently seeing will make this harder.

As lines of disagreement are drawn up and trust is on the decline, we need to find more ways to generate a consensus.

It's a question of when, not if

Make no mistake, whatever political developments take place, we are going to have to navigate these challenges.

Vanishing ecosystems, melting ice caps and harsh impacts on people’s livelihoods – none of this is subject to political persuasion, only to the physical effect of our economic and engineering choices.

At the same time, the efforts being made today are reshaping the economic context within which political leaders operate.

Changes like the accelerating pace of wind and solar deployment and the growing market of electric vehicles are now inevitable shifts in the economy, where the only questions left are pace and scale, not direction.

And just as the rise of the right in many countries is being driven by an underlying shift towards fear about our future societies, there is much more widespread environmental anxiety that drives its own level of growing political pressure.

In the end then, it’s a question of "when", not "if". There will be a green transition,* and while it probably will be messy and volatile, politics needs to evolve to guide us through stormy waters.

Eliot Whittington is Executive Director of the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.