By Maxwell Radwin

Mining can take its toll on the environment when done irresponsibly, especially in vulnerable ecosystems like the Amazon Rainforest. Deforestation and river pollution are common complaints from communities living near a mine. Heavy metals and chemicals like mercury and cyanide often kill off flora and fauna.

But that environmental loss can also be viewed as an economic one. Damaging carbon sinks and natural aquifers can be extremely costly in the long run, leading to mudslides, drought, climate change and poor air quality, among many other things.

Framing environmental impacts in economic terms can be helpful for driving home just how serious a situation has become. Dollar figures can trigger the alarm for doubtful politicians and investors.

“We’ve been focused on measuring the amount of deforestation,” said Matt Finer, director and senior research specialist of Amazon Conservation’s Monitoring of the Amazon Project (MAAP). “That’s been our unit of measure, the number of hectares of deforestation, which for me is very compelling. But I recognize that for others, it may be not as compelling as other variables like health impacts or economic impacts.”

He added, “Whether or not the deforestation data speaks to you, [the economic impact] is like another language and it’s a language that everybody speaks.”

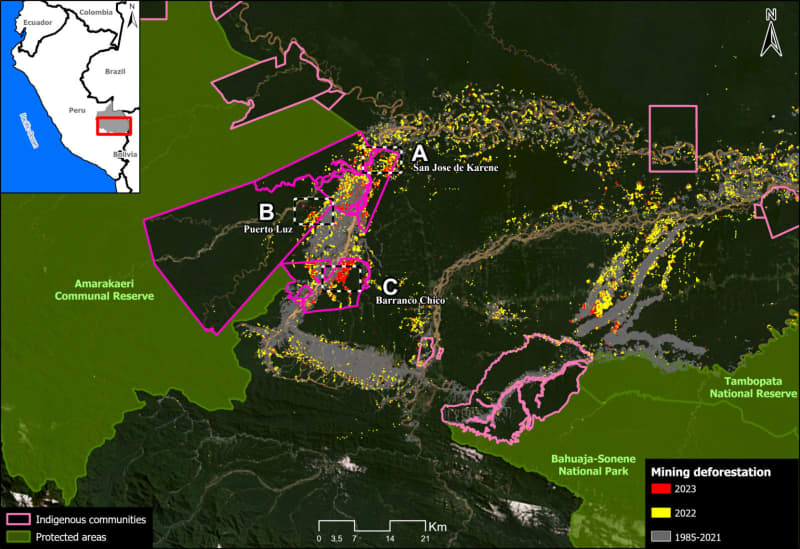

MAAP recently analyzed the environmental and economic impact in three local communities in the Madre Dios region of the Peruvian Amazon, where gold mining has torn apart the rainforest and created a public health crisis for residents. The project was carried out using the Mining Impacts Calculator, a tool created by the Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF) to quantify the economic impact of environmental damage.

Across the three communities, deforestation from mining and pollution caused a total economic loss of $593,786,943 just between August 2022 and 2023, according to the calculator. It accounted for socio-environmental impacts caused by tree cover loss, sedimentation and contamination from mercury, among other things.

Map of deforestation from mining. Courtesy of MAAP.

“We’re arriving at these estimates [taking into account] the number of people that are going to be potentially contaminated throughout the years,” said Pedro Gasparinetti, director of CSF-Brazil. “Mercury can stay in the environment for up to a hundred years.”

The economic impact of deforestation in some of the communities was massive compared to the relative forest loss, revealing just how important forest ecosystems are. In the San José de Karene community, 914 hectares (2,258 acres) of deforestation between August 2022 and 2023 resulted in $252,916,389 in economic losses.

Mining has torn through San José de Karene for decades. Forests around major water bodies, such as the Colorado and Pukiri rivers, have been almost entirely cleared in some parts, the riverbanks covered in machinery. The community is one of the hardest hit in Madre Dios, a department located in southeastern Peru where gold mining has become the top economic activity, according to USAID.

Another community in the department, Puerto Luz, saw mining destroy 270.6 hectares (668 acres) of forest between 2022 and August 2023 at a cost of $69,152,933. Meanwhile, the Barranco Chico community lost 93.3 hectares (230 acres) from 2022 to August 2023 at a cost of $271,717,621.

Authorities launched Operation Mercury in 2019 to remove illegal mining operations from some parts of Madre Dios. But it was only a temporary success, with mining operations destroying the forest in legal mining areas before gradually returning to illegal activity.

Today, officials continue to look for new ways of stopping the deforestation and pollution caused by mining in Madre de Dios. One solution might involve driving home just how much negative economic impact mining has.

“[We have to] make governments and organizations aware that it’s worth paying a little more, or giving a subsidy, an economic incentive to buy machines that don’t use mercury,” Gasparinetti said. “There’s always a cost-benefit. People have to think about whether or not it’s worth doing something and how much worth there is investing in oversight or encouraging mercury-free technologies.”

Banner image: Gold mining in Madre de Dios, Peru. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

See related from this reporter:

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay