By Ben Aris in Vienna

Other countries of Central Asia may have plentiful reserves of oil and gas, but Kyrgyzstan has huge resources of something even more valuable: water.

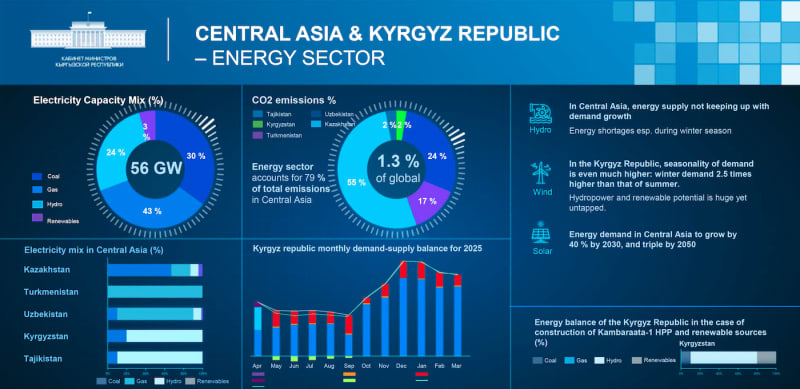

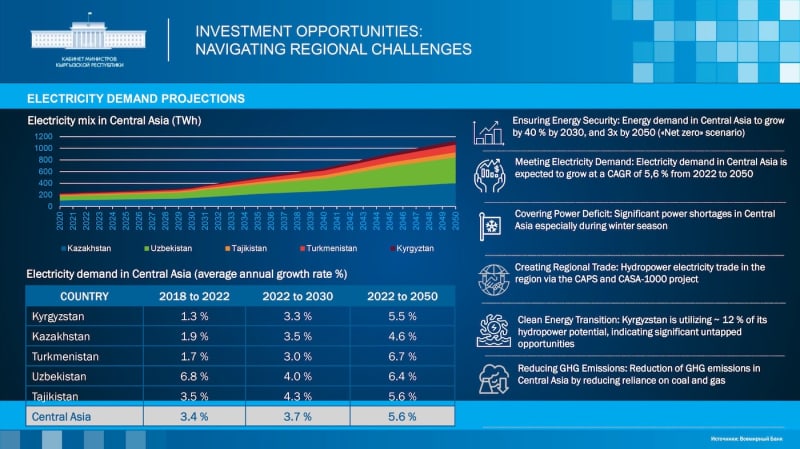

As the climate crisis unfolds and the world seeks to cut emissions, hydropower has come into its own. The five “Stans” of Central Asia are growing fast and are power hungry. Kyrgyzstan sees an opportunity: if it can become a regional electricity generation hub, it can deal with its own power deficit while also boosting its economy with a permanent source of income drawn from energy exports.

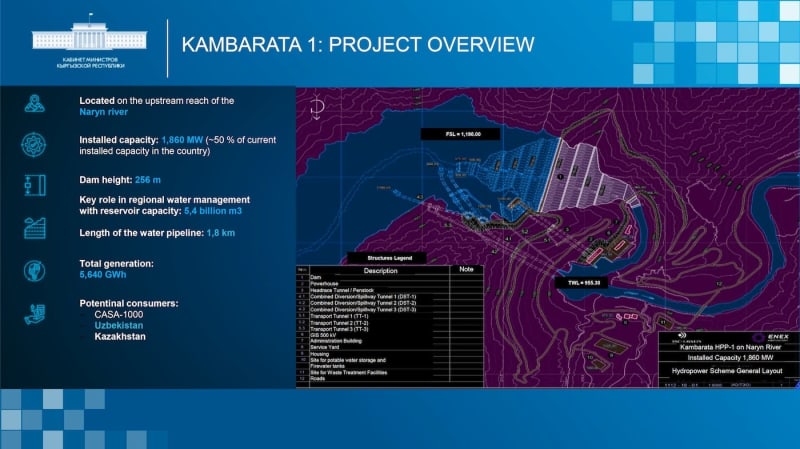

The country’s government has launched a drive to raise the $5bn it needs to realise its flagship 1.8-GW Kambarata-1 hydropower plant (Kambarata-1 HPP). The mega infrastructure would increase Kyrgyzstan’s installed capacity by half. The funding campaign began in earnest at the Kyrgyz Republic Energy Forum (KGEF) held in Vienna on June 10.

Kyrgyz Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers Akylbek Japarov presented the ambitious Kambarata-1 project on the Naryn river to representatives of the leading international financial Institutions (IFIs) and international investors.

“Kambarata-1 will revolutionise the energy sector of the Kyrgyz Republic. It is not just an important project for our country, but for the whole world and part of our collective green future,” Japarov said.

The Naryn River is fed by the glaciers and snows of the Tian Shan mountains (“Mountains of Heaven”), where it rises. It flows into the Syr Darya river in Uzbekistan, merging with the Kara Darya in the Fergana Valley.

Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan boast massive oil and gas deposits that can potentially meet all their needs.Uzbekistan, meanwhile, signed off on a 12-billion cubic metre (bcm) gas import deal with Russia in February, but it still expects power shortages in the coming years thanks to its annual GDP growth running at around 6% and expanding population. Central Asia as a whole is growing fast. Critical energy deficits have periodically beset various geographies for the past two years.

Kambarata-1 would go a long way to meeting the growing thirst for power. The plan is similar to the long-held ambition for Tajikistan’s giant (though substantially incomplete)Rogun HPP—export copious amounts of electricity to larger neighbours via the Central Asian power ring that was built in Soviet times and is currently being upgraded to better connect the five Stans.

Kambarata-1 will also help in tackling another tricky problem: water management. Both the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan are mountainous upstream countries that serve as the source of the main rivers of Central Asia. Kambarata-1’s dam will allow for better control of the water that flows to the benefit of irrigation in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, as well as being able to provide these countries with power.

'According to experts, by 2050 the population in Central Asia will increase by 27%, the demand for food will grow by 35%, and consumption of drinking water will leap by 50%,' Japarov noted. He highlighted the importance of overcoming challenges such as the region’s landlocked location, resource dependence, low financial development and climate change impacts on the region, with water already in short supply.

“Water is the lifeblood of Central Asia,” said Japarov, adding that 80.7% of the region's watercourses originate in the two upstream countries. 'In some places, the system is unable to meet electricity needs at certain times of the year, while in other places, people do not have enough water for drinking and irrigation,' Japarov said.

Competing demands for water use have historically given rise to tensions.

'Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan want to use water for irrigation in summer, while the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan need water for energy in winter. This situation affects energy and food security in the region,' Japarov continued. 'Kambarata-1 is located at the source of the glaciers. Effective operation of this hydropower plant will allow the accumulation and rational use of water resources of the Toktogul reservoir.'

It's no surprise that Kyrgyzstan’s Central Asian neighbours are taking a keen interest in the Kambarata-1 project. And the project is actually so big, it will have to be a pan-regional endeavour.

The nominal GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic in 2023 was only $14bn, but with the additional dozen small HPPs the government wants to build on other rivers in the country, the total price tag for the infrastructure rollout is around $16bn. This only becomes economically viable if the needs of the Kyrgyz Republic’s neighbours are taken into account, with the combined GDP of all five of the Central Asian countries some $450bn.

The government’s national energy plan was launched in 2021 shortly after Kyrgyzstan’s President Sadyr Japarov took over. The 12 clean energy projects that Akylbek Japarov showcased in Vienna, worth a total $16bn, have been made the government’s top priority. The hunt for investors and partners has been redoubled.

The World Bank has committed to the $500mn investment tag of the first construction phase, but Akylbek Japarov is now looking for long-term private investors to supplement the World Bank’s funding to provide two thirds of that money.

'I firmly declare that our side will provide full support and protection of the interests of the investor. In addition, 100% use of the generated electricity will be ensured,' he stated.

The height of the Kambarata-1 dam is designed at 256 metres. The volume of the reservoir will be 5.4bn cubic metres. Preparatory work has started, and construction is expected to take around 10 years.

With an installed capacity of 1,860 MW and an average annual production of 5.6bn kWh of electricity, Kambarata-1 will prove crucial in meeting the region's growing energy demand. 'The useful volume of the reservoir is 2,870mn cubic metres, and the preliminary construction estimate is more than $4bn,' Japarov said. The project includes a rockfill dam, a plant building with four hydraulic units, spillways, tunnels, a work camp and water treatment facilities.

A five-year plan was approved last October 31by the World Bank board of executive directors. On the same day, the board approved technical assistance of $5mn for updating the Kambarata-1 feasibility study.

The World Bank in Juneallocated $13.6mn to Kyrgyzstan in additional technical support funding.

With the preparatory work divided into two stages with a total cost of Kyrgyzstani som (KGS) 44.1bn ($500mn), backed by the World Bank, Japarov announced the government would commit an additional $500mn from the state budget for 2024-2030.

Of the $500mn investment into the initial construction, between $150mn to $200mn will be provided by the World Bank in the first phase, and other financiers will come in and meet the balance.

Japarov called on international financial institutions, investors and companies to participate in energy projects aligned with modern climate challenges.

'Together we can realise this ambitious vision and make a significant contribution to both the energy stability and environmental sustainability of our region,' Japarov concluded.

You can find all the KGEF presentations here.