By Philip M. Fearnside

Brazil’s Amazon deforestation has traditionally been primarily in the “arc of deforestation” along the southern and eastern edges of the forest, but highways connecting this arc, such as the BR-163 (Santarém-Cuiabá) highway, are allowing this destruction to expand to rainforest areas to the north. Of particular concern at the present time is the BR-319 (Manaus-Porto Velho) highway that would facilitate the movement of deforestation actors and processes to Manaus, in the relatively intact central Amazon, to all areas in the northern Amazon that are already connected by road to Manaus, and to vast areas in the western Amazon via planned highways linked to BR-319. BR-319 begins in AMACRO, the acronym for area near the junction of the states of Amazonas, Acre and Rondônia, which is now one of the most explosive deforestation hotspots (Figure 1)

[(https://imgs.mongabay.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2024/01/17012025/fearnside-f09.jpg)

Figure 1. Burning in 2022 in the AMACRO region that would be connected to vast areas of rainforest by Highway BR-319 and planned side roads (Photo: Nilmar Lage/Greenpeace/30/08/2022).

On 11 June 2024 Brazil’s National Department of Transport Infrastructure (DNIT) released the report of its BR-319 Working Group (Figure 2), which concluded that “there are elements to guarantee the technical and environmental viability of the complete paving of BR-319” (p. 65). DNIT has been trying for years to obtain environmental approval for its project to “reconstruct” the BR-319 (Manaus-Porto Velho) Highway that, together with planned side roads, would facilitate the deforestation of much of what remains of Brazil’s Amazon forest. The highway was built by Brazil’s 1964-1985 military dictatorship in 1968-1972, but in 1988 (three years after the end of the dictatorship) the 405-km “middle stretch” of the highway was abandoned for lack of adequate traffic to justify the high cost of maintenance. Brazil’s system of environmental licensing had been implanted in 1986, and in 2005, when DNIT proposed to “reconstruct” the highway (that is to build a new highway on the same route as the previous one), it faced environmental requirements that had not existed during the military years.

[(https://imgs.mongabay.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2024/06/16224424/br319-report.jpg)

Figure 2. Cover of the highway department’s working group report.

So began a long sequence of legal battles and failed attempts to justify the project to the licensing authority (IBAMA, the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources). DNIT finally obtained a preliminary license on 28 July 2022 in the last months of the notoriously anti-environmental presidential administration of Jair Bolsonaro. The “preliminary” license is the first in the three-step licensing process; it does not allow construction to begin, but it opens the way for obtaining the “installation” and “operating” licenses. DNIT is now trying to convince IBAMA to approve the installation license, for which the BR-319 Working Group (GT BR-319) was formed. In the meantime, legislative initiatives are moving forward to force IBAMA to approve the BR-319 project and to essentially eliminate Brazil’s environmental licensing system completely.

On 17 November 2023 the Ministry of Transportation, which includes DNIT, issued a directive (portaria) establishing the BR-319 Working Group to “present studies and proposals that promote the optimization of the highway’s infrastructure.” Obviously, this simply assumes that the project itself is unquestionable and the mandate is limited to suggestions for measures that would facilitate approval of the project rather addressing than the fundamental question of whether the highway reconstruction project should be approved and executed. The working group is defined as composed of representatives of five departments of DNIT (Article 3). Other government agencies and outside experts can be invited to “participate in meetings” (paragraph 8), but they have no say in the working group’s conclusions.

The report states “By focusing on social participation, the Ministry of Transportation mapped and invited 33 civil society organizations, representing Indigenous peoples, communities in the Amazon region and climate activists to discuss the feasibility of BR-319. Among them were Greenpeace, the Climate Observatory and the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon (COIAB)” (p. 37). The three groups mentioned have clear positions against the highway project (a fact not mentioned in the report), and the report does not mention which, if any, of these groups participated. The paragraph on civil society participation concludes by stating “However, there were no contributions or indications on the issues involving the project” (p. 37). In other words, input from civil society can be considered to be zero.

A particularly revealing portion of the document is that dealing with Indigenous peoples. The Humaitá regional coordinator of the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) is reported to have said that the Parintintins Indigenous people is in favor of the highway and “approved the studies that were presented to them in public hearings as a requirement for issuing the Preliminary License” (p. 34). Nothing is said about the other Indigenous groups, such as the Apurinã and the Mura, that are strongly opposed the project and are basically in a state of panic given the land grabbing and invasions linked to BR-319 that already occurring in and around their traditional areas.

Note that the statement by the FUNAI regional coordinator mentions “public hearings” (audiências públicas) rather than “consultations” (consultas). Another curiosity is that the report lists as an “agreed action” with FUNAI “action to define the methodology for listening to indigenous peoples and traditional communities” (p. 58) using the term “listening to” (escuta) rather than “consultation with.” These linguistic details are very important because a “consultation” is required by International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169, which Brazil signed, ratified and converted verbatim into law (Law 10.088/2019, Formerly No 5.051/2004).

A consultation is very different from a public hearing or an “escuta,” as it means that the impacted Indigenous people have a voice in the decision on the existence of the project as a whole, not just the opportunity to offer suggestions about how it is to be implanted and how damages will be mitigated or compensated, and it is understood that the consulted people have the right to say “no” (e.g., see here). None of the impacted Indigenous groups have been consulted. ILO Convention 169 and the corresponding Brazilian law are clear that all groups impacted must be consulted.

These groups are in no way limited to those within 40 km of a proposed highway, which is the current limit being used by the Brazilian government based on a 2015 interministerial directive (portaria) that defines this as what is “directly impacted” for the purpose of environmental impact statements (see here and here)). Needless to say, ministers appointed in the executive branch do not have standing to overrule a law passed by the Brazilian National Congress, much less an international convention ratified by Brazil. The current environmental impact statement for the highway project lists only five Indigenous groups as impacted. However, there are 13 groups within the 40 km limit and 63 groups within a 150 km distance, which simulations indicate would be impacted by deforestation from the highway (see here).

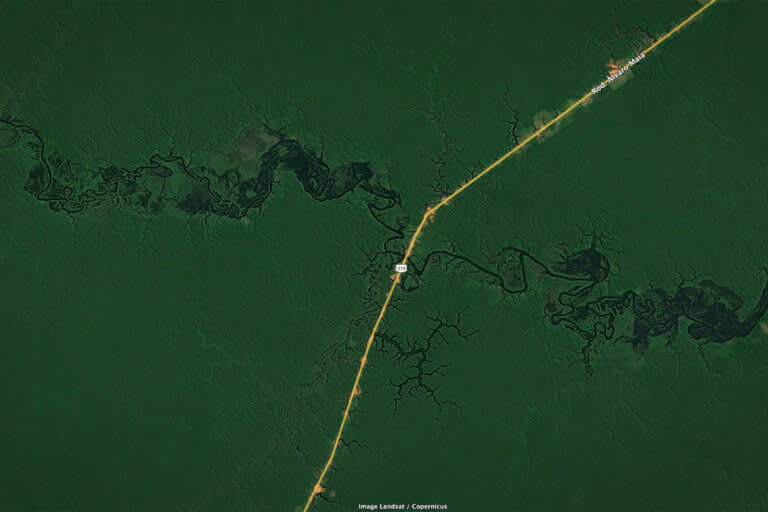

[(https://imgs.mongabay.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2024/06/16235629/BR319.jpg)

A section of BR-316 in 2013. Image credit: Landsat / Copernicus

The BR-319 highway route is currently the scene of rampant land grabbing (grilagem), which in Amazonia refers to large operators claiming government land and their subsequent maneuvers to obtain land titles. Note that the English-language term “land grabbing” has a different meaning in Asia and Africa, where it refers to foreign interests purchasing farmland to produce commodities for export, thus depriving local populations of food security. Land grabbers in Amazonia usually subdivide the grabbed land and sell it to cattle ranchers, who will then deforest for pasture. There is also invasion of government land by small landholders, who will themselves clear and plant, also usually planting pasture; they often later sell their plots to medium and large ranchers who will consolidate the purchased plots into larger landholdings.

The practice of legalizing these claims, both large and small, is self-perpetuating, as it encourages ever more land grabbing and land invasion. What the current Brazilian presidential administration does about this problem has tremendous consequences, and indications are that there will be no end to the cycle of land “regularization.” This is a euphemism for legalizing illegal land claims that falsely implies that the claimants have a right to the land, while, in fact, those who are traditional riverside dwellers and others that have lived for generations in government land represent a minuscule fraction of the area being legalized (see here and here).

The working group report mentions “land regularization” (regularização fundiária) through actions to create settlements and to regularize “undesignated lands” (terras não destinadas) (p. 21). For the small landholders this refers mainly to either legalizing the invaded land as settlements (assentamentos) or offering these invaders lots in a settlement created elsewhere. In the case of “undesignated lands” it means legalizing the claims of land grabbers. These are basic drivers of deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia. Nothing is included in the report of plans to remove illegal invaders or block legalization of land grabbing claims.

A benefit of the highway mentioned in the report is “transport of agricultural products on the Manaus – Rondônia route” (p. 28). It is notable that there is no discussion of the economic viability or lack or viability of the highway. In fact, as shown by existing economic studies, the highway is completely inviable economically, despite over two decades of continuous disinformation disseminated in Manaus about this aspect of the project (see here, here and here).

Another supposed benefit mentioned is “connections with the state of Roraima” (p. 28). This is notable because, when it comes to planned measures to minimize impacts, the report limit discussion strictly to the roadside along the highway route itself. Not mentioned at all are the drastic potential impacts of deforestation along planned highways connecting to BR-319, such as AM-366 and AM-343 that would open the vast “Trans-Purus” rainforest area to the west of BR-319. The state of Roraima is already connected to Manaus by road (Highway BR-174) and would receive migrants from Brazil’s “arc of deforestation” in southern Amazonia via BR-319. Roraima is known as the Amazonian state with the least environmental control, where the main politicians even support the illegal gold miners invading the Yanomami Indigenous Land (e.g., see here and here).

The report begins by stating that “The main challenge is to ensure that the project is aligned with the sustainable development of the region” (p. 5). This is much more than a “challenge;” it is a question that must be considered in deciding whether to go ahead with the project at this time in history, or to wait until a future time when governance and sustainable development are established norms of behavior rather than mere discourse and good intentions. The BR-319 route is essentially a lawless area today, and completely unrealistic governance scenarios have long been used in attempts to gain environmental approval (see here and here). The working group report continues this tradition.

The working group report repeatedly mentions the BR-163 (Santarém-Cuiabá) highway as an example that could provide a model for governance along BR-319. The irony of this is considerable, as BR-163 is an example of the exact opposite: it demonstrates the danger of unrealistic expectations of governance controlling deforestation and other environmental impacts that, in practice, are largely outside of government control. BR-163 was licensed in 2005 on the strength of the Sustainable BR-163 Plan but history did not follow the plan. BR-163 became a major hotspot for land grabbing, invasion of Indigenous Lands and illegal deforestation, logging and gold mining (e.g., see here). It was also the place where the “day of fire” was organized in 2019, when ranchers across the Amazon set fire on the same day to show their support for then-President Bolsonaro’s anti-environmental policies.

The report does not discuss the impacts of the project even in the restricted area along the roadside itself. Instead, it provides a sequence of brief mentions of planned measures, such as passages to allow wildlife to move from one side of the highway to the other. No data or other information is included to back up its claim that the highway is environmentally viable, other than the simple affirmation that this is the case. Tellingly, the only references cited in the document, aside from the website for official deforestation data and a 2008 Ministry of the Environment working group report, are judicial decisions and ministerial decrees. This obviously avoids having to deal with the considerable literature that indicates the grave impacts of the project and contradicts the working group’s conclusion of “environmental viability” (see reviews here, here, here, here and here).

This article is an updated translation of a text by the authors that is available in Portuguese on Amazônia Real.

This article was originally published on Mongabay