By Joshua Daskin and Jen Guyton

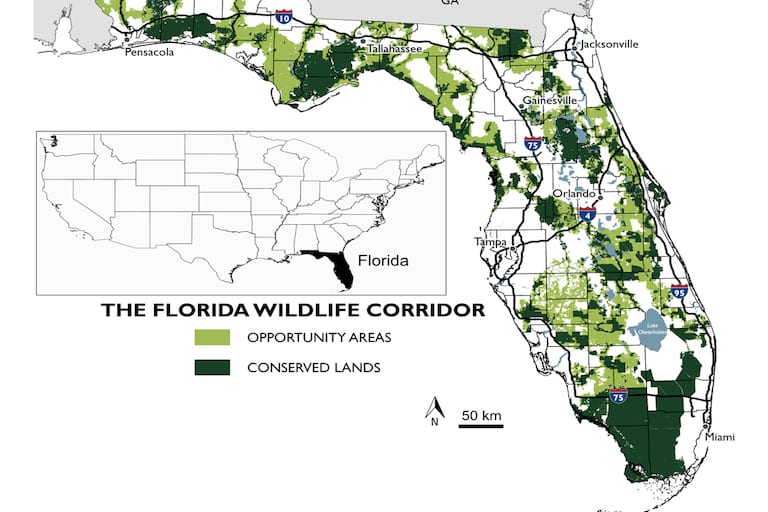

In Florida, one stunningly ambitious habitat conservation program is creating a model for a future in which people coexist with nature. Spanning the length of the state—from Alabama to the Everglades—the Florida Wildlife Corridor is a vision for a continuous, 18-million-acre tract of land that aims to keep nearly 50% of the state undeveloped (Figure 1).

The challenges are great: Florida has among the fastest-growing state populations, averaging 1000 additional residents per day in 2023. As people flock to Florida, the price of land—whether for conservation or development—rises. Between 2001-2019, over 525,000 acres (820 sq. miles) of natural lands, timberlands, crops, and ranch lands were converted to development, an area almost 15 times the size of Miami.

In the face of advancing development, conserving nearly 50% of Florida will require every tool in the toolbox. Thus far, conserving the corridor has primarily been achieved through public acquisition (outright purchases to create new conservation areas) and conservation easements (in which the landowner retains the land but relinquishes certain development rights). Progress has been promising: since the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act was approved in 2021, state funding and agencies have helped private landowners conserve an additional 200,000-plus acres within the corridor.

Figure 1—Map of the Florida Wildlife Corridor. Dark green conserved lands are already protected, while light green opportunity areas still need to be protected in order for the corridor to be complete.

However, we can conserve more, faster by employing other tools, too. We are heartened by budding efforts to protect the corridor—and other large landscapes like it—with diversified toolkits, especially by investing more in payment for ecosystem services (PES) programs to complement acquisitions and easements. Paying landowners to maintain and improve ecosystem services on their lands can quickly contribute to economic sustainability for landowners, reducing pressure to sell their land to developers. PES can also potentially provide conservation at a lower public cost than acquisition or easements and/or buy time to find public or private funds for permanent easement or acquisition.

About 55% of the corridor is already protected (most in the decades before the Act), but the corridor’s unprotected 45% is in private hands. While the benefits to wildlife of a fully protected corridor are vast, the corridor also benefits people by providing flood mitigation, recreational opportunities, climate benefits, ecosystem services, and economic opportunities. Conserving the corridor is a race against time: there is a very real risk that any given landowner could sell to developers. If critical connections are lost, the corridor can’t exist as a contiguous band of habitat that enables statewide animal movements.

Given the pressure of development, there are drawbacks to limiting our toolkit to land purchases and easements—some landowners, for example, may be attracted to the income that conservation deals can provide, but are not ready for the perpetual commitment of a sale or easement. Furthermore, the realities of public funding mean that there may not be enough public money to acquire or put easements on all remaining unprotected land within the corridor boundary.

The corridor would protect the habitats of many kinds of wildlife, from iconic Florida animals like alligators and flamingos to the common ones, like this great horned owl. Image by Ethan Coyle/Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation.

Payment for ecosystem services

Consider a 500-acre forestry operation. In addition to their value as a timber operation, those 500 acres may have immense social and environmental value: clean water flows to reservoirs and wetlands, birds flit through the canopy, frogs call from the undergrowth, and turkey and deer draw hunters. This forest is extremely valuable to the people who will use the water, see the wildlife, and hunt the game. These values are called ecosystem services, or simply put, the benefits that people get from nature.

Payments for ecosystem services are agreements that allow public agencies or private interests to make payments to secure from a landowner the provision of clearly defined specific ecosystem services including, for example, protection and restoration of water resources, improved management of wildlife habitat, and long-term conservation of forest and grassland soils and native plants.

Privately held lands within the corridor provide myriad ecosystem services, but those services are at risk of being lost if land is converted to development. Paying landowners for these services may reduce the risk that they will sell to developers, providing, at the least, an interim conservation solution.

PES is not one-size-fits all: the type of PES scheme that will be successful will vary depending on the habitat and socioeconomic setting. One of us (JD) recently co-chaired a year-long Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation working group on PES in which Florida landowners, agency staff, non-profits, and researchers shared their aspirations for how PES can better contribute to the corridor’s conservation. The group worked to align on the outstanding challenges for these complex but promising programs.

For the corridor, the group determined that focusing on water and biodiversity services will be most effective at present. Already, Florida has a reliable example of PES for water in the Northern Everglades, which has demonstrated the value of storing excess water on private land and rehydrating wetland habitats. Biodiversity conservation, on the other hand, is a core goal of the corridor, making biodiversity an apt service to support in the corridor. Indeed, the state wildlife agency is in the early stages of a new habitat-based PES program. Elsewhere, PES has proved effective in a limited number of long-term and large-scale conservation efforts. Often, PES has taken off in the form of carbon markets, the huge promise and peril of which have spurred no less than the U.S. White House to issue new guidelines on their implementation.

However, PES programs are not trivial to design and implement and have faced challenges elsewhere in recent years due to imprecise accounting, but here we outline the principles that will lead to credible PES programs, both in Florida and beyond.

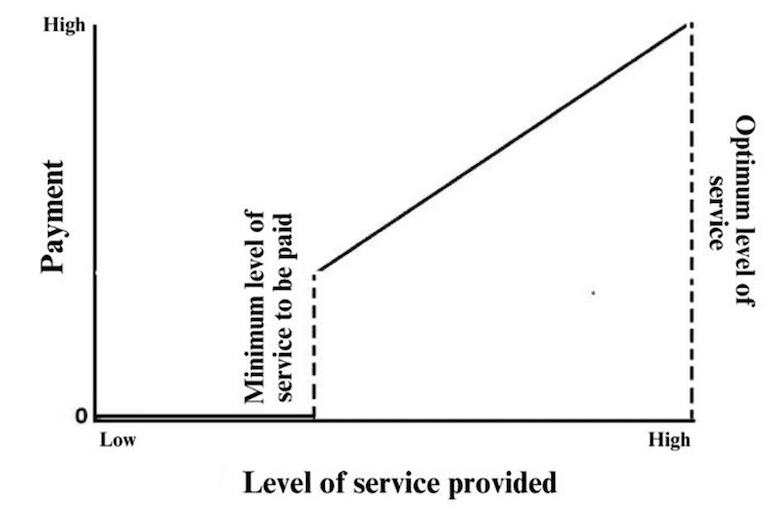

Figure 2—Illustration of the general recommended approach to pricing PES. Only sellers providing a certain minimum level of service are compensated. Additional services provided are compensated at a higher rate.

Principles for credible PES programs

PES Programs must address several key principles in the program design process, each requiring careful consideration and input from numerous stakeholders. The key considerations for PES program design include:

a) Additionality. No buyer—of any goods or services—would want to pay for something they would have received anyway. In the past, some high-profile programs have exaggerated the services attributable directly to contracted practices, as opposed to services that would have happened anyway. If implementing a PES program does not result in additional ecosystem services, the program is meaningless. For example, if a forest is not at risk (e.g., a landowner never intends to log it), there is no opportunity for buyers to ensure more ecosystem services are provided by avoiding deforestation. However, it is often very difficult to estimate the degree to which an uncompensated landowner would continue providing a service in the future, given unknown potential changes in financial, development, personal, and agricultural conditions. Therefore, we recommend paying willing sellers an entry-level baseline amount, and then increasing payment significantly for higher levels of service provision (Figure 2). To collect higher levels of payment, sellers would have to improve their conservation-friendly practices.

b) Leakage. Securing provision of an ecosystem service in one location should not lead to the degradation of the same ecosystem service in another location. For example, if development is avoided where habitat is provided on one ranch, that same development and the impacts it would have had on the PES site’s conservation values (e.g., species, water, carbon stocks) should not be diverted elsewhere. Avoiding leakage is aided where the entity monitoring credit sales can oversee the entire geography or sector of relevance. This could be regional (e.g., watershed protection), national (e.g., timber markets), or global (carbon emissions).

c) Baselines and monitoring. Monitoring is needed to ensure compliance to the conditions of the contract, and that desired outcomes of the program are being achieved. Unfortunately, through improper accounting, some markets have sold more credits than justified, underscoring the need for good baselines. We need clear and consistent methods for documenting pre-contract conditions and for measuring services provided. Oversight by an agency or independent monitoring group formally charged with the responsibility and resourced to implement a PES program creates confidence that funds, whether public or private, will be directed to paying for measurable services and ensuring results.

d) Beware tradeoffs and confirm co-benefits. A credible PES program must ensure that ecosystem service provision is not having disproportionate negative impacts on other values. For example, planting forests where grasslands are the natural ecosystem will likely have negative impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem function.

Given the scale of challenges conservation faces, to its most ambitious goals like 30×30 or Half Earth, we must think creatively about how to incentivize voluntary conservation while bettering rural economies. PES, when implemented with carefully considered project design, is a potentially impactful option.

*

Joshua Daskin, Ph.D., is the director of conservation at Archbold Biological Station, a nonprofit research, conservation and education center in Central Florida. He works to put science into action for credible conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems statewide and beyond.*

Jen Guyton, Ph.D., is an independent science communicator and storyteller whose photography and writing has appeared in various international publications including National Geographic, Smithsonian, and Audubon Magazine.

Banner image: The corridor would preserve myriad landscapes and ecosystems like pine flatwoods. Image by Ethan Coyle/Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation.

See related news of wildlife corridors:

This article was originally published on Mongabay