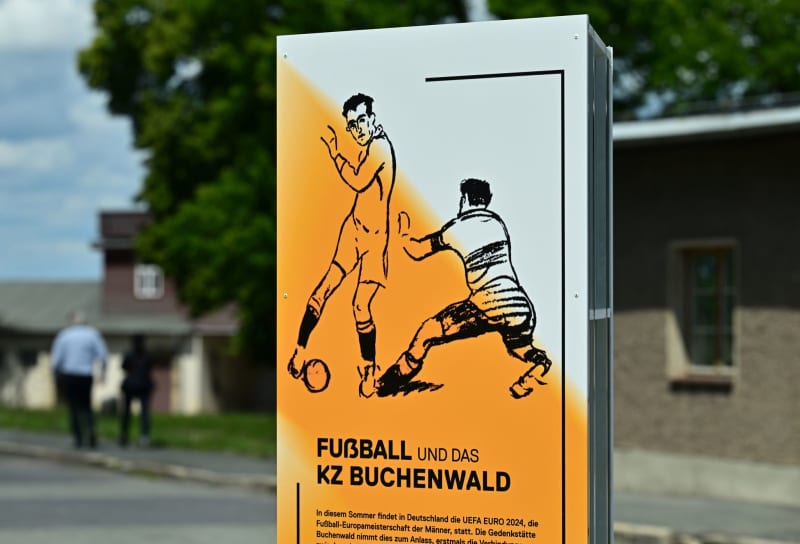

As Germany hosts this year's European Football Championships, one former concentration camp is running an exhibition about the links between the game and the Nazi death camp in Buchenwald.

For many footballers and club officials, their careers came to an end when the National Socialists seized power in 1933. Some were marginalized and persecuted, while others were imprisoned for resisting the Nazis.

Many were sent to death camps such as Buchenwald, close to Weimar, where the Nazis built one of the first and largest concentration camps within Germany's borders in 1937.

Prisoners were brought to the camp from all over Europe and the Soviet Union and included Jews, Poles and other Slavs, the mentally ill and physically disabled, political prisoners, Romani people, Freemasons, and prisoners of war.

Prisoners worked primarily as forced labour in local armaments factories. Tens of thousands were executed or died due to insufficient food and harsh conditions.

But the SS guards responsible for all this death and suffering also allowed a select few to play football, offering this sport an opportunity to escape the daily camp routine and its dangers - even if only briefly.

One such inmate was Louis de Wijze, who had played football at another concentration camp and remembers being able to exchange the "boring, smelly camp clothes with the hated number on them for the crisp, colourful football shirts."

For the first time in a long time, I no longer felt like a number, a colourless herd animal, he said.

"Perhaps a thousand kilometres away from home, where death has become the all-dominant factor around us, I can still immerse myself completely in the intoxication of the game," he said of life at Auschwitz, another German Nazi death camp.

"For an hour and a half, there are no more orders, no more truncheons or gallows. I sink blissfully into the gurgling applause and let myself drift on the waves of cheers. After every game I win, I'm firmly convinced that the hell we have to live in here will soon be behind me like a bad dream."

The new memorial exhibition staged outdoors in Buchenwald focusses on the professional players and club officials among the prisoners of the concentration camp.

Among them was the later vice president of the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), Josef Gerö (1896-1954). He was imprisoned in Buchenwald concentration camp from September 1938 to July 1939.

He later became Austrian Justice Minister, President of the Austrian Football Association and the Austrian Olympic Committee.

But other famous footballers perished at the camp, including the former national team players from France and Hungary, Eugène Maës and Henrik Nádler.

The were two sides to the use of football in the concentration camp is ambivalent, says Rikola-Gunnar Lüttgenau, spokesman for the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation, in Buchenwald,

"For the inmates, football matches in the camp - as players and as spectators - could be a way of escaping the horror for a short time," he says. "But in contrast, the SS used the games to cover up the criminal nature of the camp."

Although the museum says some of the prisoners were allowed to play football on the camp grounds, most were unable to do so due to the gruelling hard labour and starvation.

But in April 1939, the SS camp management organized a first football match, pitting a team of Jewish prisoners against a team of non-Jewish prisoners.

The fact that the SS took part in the league in the region of Thuringia "quite normally" with its own team also contributed to the normalization of the crimes in the concentration camp in the public perception at the time, says Lüttgenau.

At times, this team was coached by a former German international: Fritz Förderer was also a coach and groundsman for the city of Weimar at the time, the museum says.

The museum also has a website that tells the stories of others who were held in Buchenwald, with stories of Dutch resistance fighters, Viennese musicians and Italian socialist footballers.

The "Football and the Buchenwald Concentration Camp" exhibition at the Buchenwald Memorial in Weimar, Thuringia, is about two or three hours by train from the Euro 2024 host cities Berlin, Leipzig, Frankfurt and Dresden. It runs until August 31.