By Karla Mendes

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network where Karla Mendes is a fellow.

ARARIBOIA INDIGENOUS TERRITORY, Brazil — Cattle are being illegally raised in the Arariboia Indigenous Territory in the Brazilian Amazon, amid a record-high number of killings of the region’s Indigenous Guajajara inhabitants, a yearlong Mongabay investigation can reveal.

Commercial cattle ranching is banned on Indigenous territories in Brazil, but our investigation found that large plots in Arariboia’s southwestern region have been used for ranching.

Mongabay visited Arariboia in late 2023, where we witnessed cattle being raised on Indigenous land. We then analyzed satellite images, conducted spatial analysis to investigate the ranches, and built a database of land leases, reports of illegal cattle ranching and logging, and incidents of violence against Indigenous people in the area.

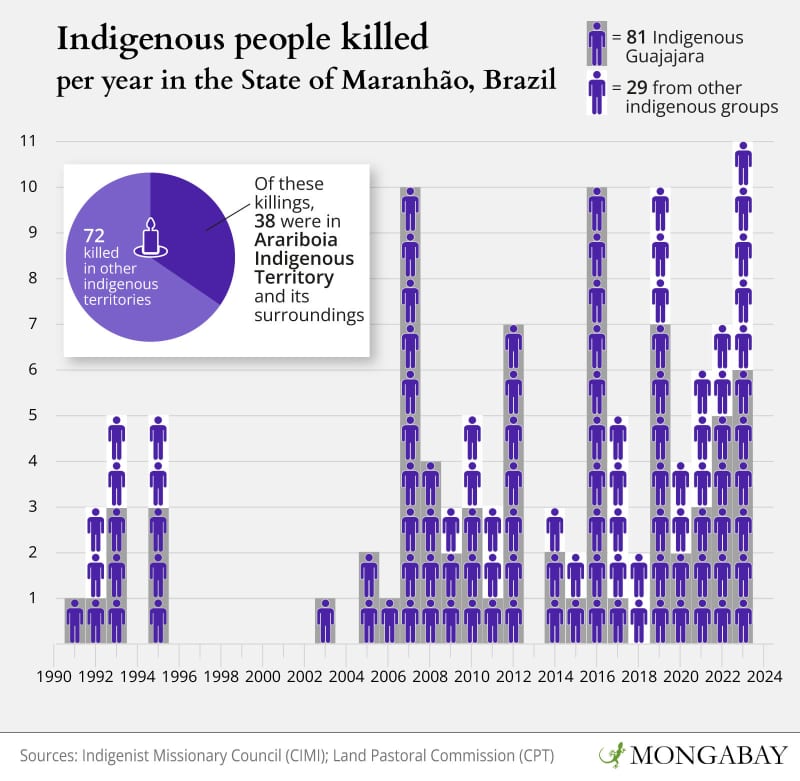

Our investigation found a clear rise in environmental crimes in the region in mid-2023, the deadliest year for Indigenous people in Arariboia since 2016. With four Guajajara people killed and three others surviving attempts on their lives, last year equaled the number of killings in 2007, 2008 and 2016, when four Guajajara Indigenous from Arariboia were also killed, the highest number since the first killing in Arariboia was recorded in 1992. The spike in killings runs contrary to the overall data for Brazil, which recorded in 2023 its lowest number of murders since 2010, according to government data. Maranhão, the state where the Arariboia territory is located, was one of the five states that saw an increase in the number of killings.

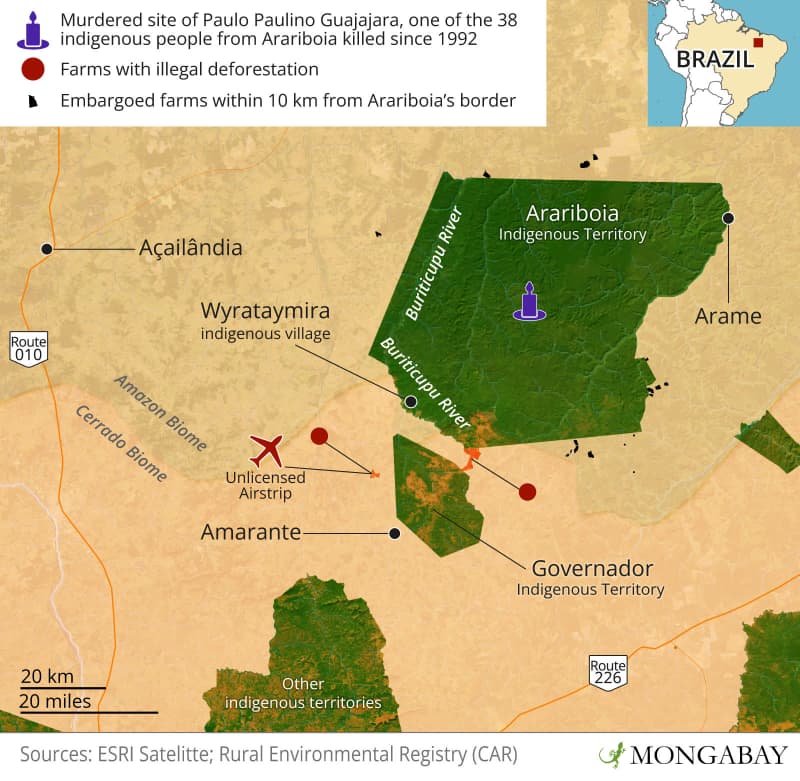

The findings show a pattern of targeted killings of Indigenous Guajajara amid the expansion of illegal cattle ranching and logging in and around Arariboia: we tracked several dozen illegal or suspicious activities inside Arariboia and in its surroundings; the hotspot killing areas coincide with the bulk of the tracked activities, with police operations curbing illegal logging and embargoed areas due to illegal deforestation. There’s no evidence that the owners of the businesses were responsible for the killings.

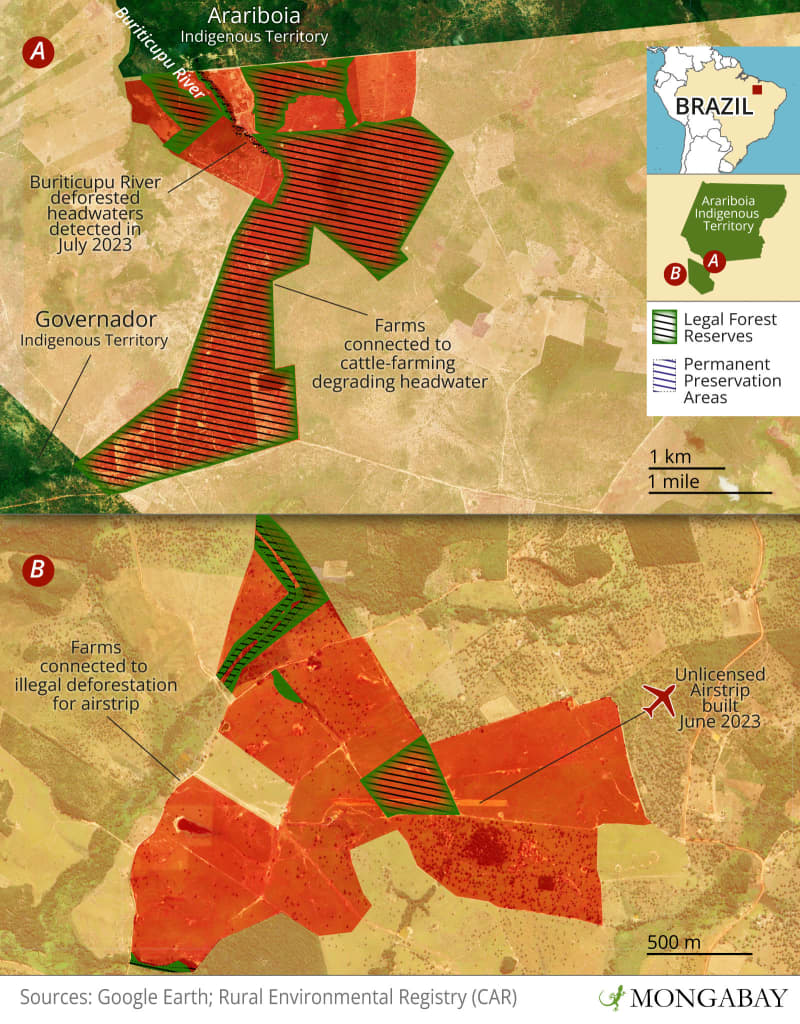

Beyond the crimes inside Arariboia, our investigation also found illegalities in its surrounding areas. Although the location of farms around Arariboia is not illegal, we found deforestation in breach of Brazil’s Forest Code inside these areas. In July 2023, illegal deforestation was recorded on the banks of the Buriticupu River headwaters, which the Guajajara people depend on for their livelihoods, less than a kilometer (0.6 miles) from the Arariboia Indigenous Territory. A month earlier, construction began on an unlicensed airstrip about 17 km (10.5 miles) from Arariboia and 4 km (2.5 miles) from the neighboring Governador Indigenous Territory.

In both cases, the associated deforestation occurred in areas protected by law, which is a crime according to the country’s Environmental Crimes Law. The logging and airstrip are linked to four farms that also overlap each other, which is an indication of unresolved conflict over land ownership. One of the farms also invaded the Governador Territory.

The farmers claiming ownership rights over three ranches next to Arariboia, identified in this investigation, have been sued for environmental crimes, land grabbing and money laundering, charges which they contest.

Maranhão state’s environmental secretariat (SEMA) also confirmed that no licenses were found for the airstrip and said it would carry out an analysis of the self-declared environmental registration (CAR) of all four ranches overlapping the airstrip area “as soon as possible,” adding that the CAR of one of the farms was previously canceled and the CAR overlapping the Governador territory has a pending status.

Arariboia “has a big problem because its borders are not well protected,” says Hilton Melo, a federal prosecutor focused on Indigenous issues based in São Luís, the Maranhão state capital. “This land has suffered a lot of harassment, many attacks, both from the south-north direction and from the east-west direction.”

Guajajara children from the Arariboia territory playing in the Buriticupu River. Image by Ingrid Barros for Mongabay.

Drone imagery reveals a deforested area on the banks of the Buriticupu River behind a thin line of trees that was left visible in front of a cattle farm along the borders of the Arariboia territory. Image courtesy of the Ka’aiwar Indigenous Association of Forest Guardians of the Arariboia Indigenous Territory.

Overlapping claims

The Amazon Rainforest covers about a third of Maranhão state in Brazil’s northeast. Arariboia, the state’s second-largest Indigenous territory, is a green island that spans more than 413,000 hectares (1.02 million acres) — more than three times the size of the city of São Paulo — in a sea of deforestation.

Arariboia’s southwestern region, which Mongabay visited last year, sits on the boundary of the Cerrado, a vast tropical savanna spanning several states in eastern Brazil, and is one of the most threatened parts of the Indigenous territory.

Arariboia was officially recognized as Indigenous land by the federal government in 1990 and is legally protected against the incursion of outsiders. Yet reports of illegal cattle ranching, logging and poaching from the Guajajara Indigenous and authorities remain commonplace.

Spatial analysis of federal land data reveals 15 embargoed farms have been established on the borders of Arariboia, with some of the concessions a short distance from land demarcated for Indigenous use. An embargo is an instrument used by environmental agencies to stop activities that are damaging the environment or that are in breach of environmental laws and regulations. The majority of farms around Arariboia were embargoed for illegal deforestation in protected areas and prevented from carrying out agriculture and cattle ranching activities.

Of the total embargoed farms, nine are located in the Arame and Amarante regions — four and five, respectively. Of these nine farms, IBAMA embargoed six of them for illegal deforestation in protected areas; two farms are prevented from moving forward with cattle ranching and the last farm cannot move forward with any activity.

Graphic by Andrés Alegría/Mongabay.

Several of those farmers connected to illegal deforestation in Arariboia’s surroundings have been the subject of legal action or investigation for alleged environmental and corruption offenses, which they all deny. These lawsuits are ongoing under state or federal courts in Maranhão.

According to CAR records and spatial analysis, one of the farms located in the illegally cleared area on the Buriticupu River banks is registered to farmer Francisco Alves Ferreira, who is the subject of a lawsuit over alleged land grabbing, according to Maranhão state court records seen by Mongabay. Ferreira didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment. In his testimony in the lawsuit, Ferreira denied the accusations. The case is ongoing in state court in the town of Amarante; a preliminary hearing was scheduled for June 25.

Another farm linked to the illegal deforestation was listed on the CAR registry by farmer Antônio José Alves de Sousa. It encroaches on the Governador Indigenous Territory, just 4 km from Arariboia, spatial analysis of the polygons of the farm’s CAR record shows, which was also confirmed by SEMA. Sousa has been renting out a property in Maranhão to Funai, the federal agency for Indigenous affairs, for a decade. Sousa didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment.

The deforested area also overlaps with a farm claimed by Adirceu Alves da Silva that was previously embargoed for illegal deforestation by IBAMA, the country’s federal environmental agency. Silva is also being sued by the Maranhão Federal Public Ministry for environmental crimes. Silva didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment; he denied the accusations in his testimony. The lawsuit is ongoing in a federal court in the city of Imperatriz.

In an emailed statement to Mongabay, SEMA said it was aware of the overlap of Sousa’s farm with the Governador territory. It said the status of the farm’s Rural Environmental Registry (CAR), a compulsory but self-declared document used for environmental purposes, is “pending” since 2021, after the environment and agriculture ministries determined that the CARs overlapping Indigenous territories should be granted such status.

SEMA said it would undertake reviews of the three other farms where our investigation found illegal deforestation bordering the Buriticupu River. It said it conducted a search on its system for all farms larger than 300 hectares (741 acres) that overlap with Indigenous lands in Maranhão and would cancel their registration after the due administrative proceedings.

In the unlicensed airstrip area, three farms are claimed by freight transport businessman Fabricio Lima Gouveia, who is the subject of a criminal lawsuit for alleged embezzlement, money laundering and corruption by the Maranhão State Public Ministry. Gouveia didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment; in his testimony in the lawsuit, he denied the accusations. The case is pending in a state court in the town of Amarante.

Graphic by Andrés Alegría/Mongabay.

The Guardians

José Maria Paulino Guajajara, whose son Paulo Paulino Guajajara was killed in an ambush by loggers in 2019 — his mother and his brother-in-law were also allegedly killed by loggers — says illegal incursions by outsiders bordering his village have been going on for years. In response, a decade ago the Guajajara set up a network to defend the region called the Guardians of the Forest.

First, José Maria says, outsiders took control of the area and set up plantations, before selling the land to cattle ranchers. The Brazilian Constitution prohibits the sale of lands from Indigenous territories. Satellite imagery shows the area was cleared in 2016 and some parts even earlier.

The village where José Maria lives is surrounded by large fenced cattle ranches. Two farm gates block passage on the unpaved road that leads to his village. Satellite imagery indicates that 6.5 hectares (16 acres) were deforested next to his village between June-July 2016. On the other side of the road, our analysis points to deforestation before 2016, with houses built there in 2015 — no satellite images are available prior to 2015.

“They [the farmers] don’t want us Indians to go to the other side anymore,” José Maria says of the land where the ranches are now. They’re also prevented, he adds, from taking straw — a traditional material used to cover houses in Indigenous villages — from the area, while cattle from the farms have destroyed his vegetable garden, a key source of food for his family.

The presence of cattle ranching inside Arariboia, the Guardians say, is also driven by a strategy of co-optation, whereby Indigenous Guajajara are persuaded to rent the land for pasture to non-Indigenous farmers. According to the Guardians, non-Indigenous men who have married Guajajara women also brought livestock into the territory, while some Guajajara are tempted by the profits that illegal land deals can bring. Leasing of Indigenous lands is also prohibited by the Constitution.

“They [non-Indigenous ranchers] arrive here in the community and often say to the Indians: ‘Do you want to lease a piece of land to raise cattle? It’s good for you.’ But in reality, it’s not,” forest Guardian Laércio Guajajara says, pointing to brand-new fence posts inside Arariboia. “Here, you can see that in the future, where we are in this mountain range, everything will be destroyed by cattle, like this part of the Cerrado.”

Laércio says the ranchers “think they own the territory” and believe they “have more rights than the Indians” because of their wealth. “They pay to devastate the territory to plant grass, to fence it off, they put up [fences], and with that our territory is shrinking more every day. The advance of grazing is uncontrolled.”

He points to the visible difference between the landscape inside and outside the territory. “On the white man’s side, there are hardly any trees. On our side here, even though it’s a bit burnt, it’s very different: only green here.”

“Guardians of the Forest” Paulo Paulino Guajajara (left) and Laércio Guajajara (right) pose for a photo before going on patrol in the Arariboia Indigenous reserve, in Maranhão state, on Jan. 30, 2019. Image by Karla Mendes/Mongabay.

José Maria Paulino Guajajara (right), father of Paulo Paulino Guajajara, with Paulo’s brother (at the front) and Paulo’s kid (right), who is being raised by him. The village where José Maria lives is surrounded by farm gates and large fenced cattle ranches. Image by Ingrid Barros for Mongabay.

Legal loophole

The land conflicts in Arariboia derive from a technicality in Brazilian law that requires a buffer zone of 10 km (6 mi) and stricter requirements to issue environmental licenses for ventures next to conservation areas, but not around Indigenous territories.

A loophole in Brazilian legislation — Decree No. 99.274/90 — defines buffer zones for protected areas known as conservation units, which include national and state parks. Under the rule, activities in surrounding areas must be approved by the National Environmental Council (Conama), but this isn’t the case for Indigenous territories.

Brazil is a signatory to international conventions requiring consultation with, and consent by, Indigenous and traditional communities for projects that may affect them directly. Following these treaties, the country usually sets buffer zones for large projects, like dams, and socioenvironmental impact studies as part of the licensing process. However, agriculture and cattle activities go through a simplified licensing process by each state, which doesn’t require prior consultation or buffer zones.

Given this loophole, the location of the farms around Arariboia is not illegal. However, if there were a 10-km buffer zone around the Indigenous territory, it could have prevented environmental crimes in and around its surroundings, authorities say. Satellite image analysis shows nearly 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) of native vegetation within 10 km from Arariboia’s borders was lost between 2008 and 2023, according to Brazil’s space research agency, INPE. Accounting for all data going back to 1988, when INPE started tracking deforestation, forest loss in the immediate surroundings of the territory totaled 188,998 hectares (467 acres).

In December 2023, Maranhão approved law nº 12.169, dubbed by critics the “land-grabbing law,” that could lead to more than a ten-fold increase in the land area open to exploitation.

An ongoing lawsuit in the Supreme Federal Court may lead to the law being voided if found to be unconstitutional, but prosecutors and land activists are concerned that if the law stays in place it will continue to worsen existing disputes and fuel further conflicts in the state.

It’s a “misconception” that cattle ranching and agribusiness have no impact on Indigenous territories, says Ciclene Maria Silva de Brito, a superintendent at IBAMA. “How can you take away the [native] vegetation [around Indigenous territories],” Brito says, “put in another one [pasture], add [agricultural] inputs there and there won’t be any impact?”

Guardians of the Forest pose in front of posters featuring killed guardians Janildo Guajajara (top) and Paulo Paulino Guajajara (bottom). The posters say, “State agents are complicit in violence against Indigenous peoples” and “More than 500 years of genocide against Indigenous peoples. No more murders!” Image by Ingrid Barros for Mongabay.

Rising violence

Between 1991 and 2023, 81 Guajajara were killed in Maranhão, more than two thirds of total killings of Indigenous people in the entire state, according to data from the Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples (CIMI), an advocacy group affiliated with the Catholic Church, and from the Land Pastoral Commission (CPT), an arm of the Catholic Church that works with Brazilian rural workers seeking agrarian land reform. None of the perpetrators have been brought to trial.

Almost half of these killings, 38, happened in Arariboia, the database shows. Six members of the Guardians of the Forest were killed, the Guajajara people say. The bulk of the killings, 26, happened in areas in the nearby towns of Arame and Amarante.

In early January 2023, there were two attempted killings of Indigenous Guajajara who were shot in the head in Arariboia, close to the town of Arame; in late January, an Indigenous Guajajara and a public health official were also killed in the Indigenous territory. One June 13, a Guajajara Indigenous died after being run over close to Arame, the Guardians told Mongabay.

The Brazilian Constitution prohibits the sale and leasing of Indigenous lands, and the Guardians say they’ve faced threats, including shootings, in their fight to protect their territory. The constitutional obligation to protect Indigenous lands lies with the federal government, but in the absence of effective federal enforcement, the Guardians say, they’ve had to take things into their own hands to ensure their constitutional rights and protect their land.

The Constitution says Indigenous territories are demarcated for the permanent possession and exclusive usufruct of Indigenous peoples, aiming to guarantee the self-determination, autonomy and protection of their rights, as well as their active participation in the management and preservation of these territories.

Graphic by Andrés Alegría/Mongabay.

“Look at all the cattle there,” says forest guardian Olímpio Iwyramu Guajajara, pointing to cattle a few meters from the Arariboia border.

“We’re going to use these coordinates for the Guardians’ intelligence work, in order to bring it to the attention of the competent authorities,” he says, urging officials to bring those responsible to justice.

Mongabay built a database with the coordinates of our field reporting and the Guardians’ coordinates recorded in several dozen photos to document environmental crimes in and around Arariboia, including the ones already filed in documents to authorities urging the due measures; we also added the coordinates of environmental crimes we found in lawsuits. Beyond conducting an in-depth analysis in the built database, we also analyzed satellite images and conducted spatial analysis into key areas we witnessed or reported environmental illegalities. We further analyzed the locations of the Arariboia’s Guajajara Indigenous killings and cross-referenced them with our database and with data we obtained of the Federal Police raids against illegal logging in the region and also with IBAMA’s database of embargoes.

Our analysis found a pattern of the killings with records of environmental crimes in and around Arariboia. The majority of the killings occurred in the surrounding areas of the towns of Amarante and Arame, the hotspot of the Federal Police raids, the IBAMA’s embargoes, and of the Guardians reports of illegal logging and illegal cattle in Arariboia’s borders. No evidence has surfaced linking the violence to these holdings.

Graphic by Andrés Alegría/Mongabay.

The ranchers

Satellite image analysis of the unlicensed airstrip shows that construction started in June 2023. The airstrip overlaps with public land in the federal government’s land management system SIGEF, which may be an indication of land grabbing, authorities say. The airstrip is one of many built in the Brazilian Amazon in recent years that NGOs and researchers tied to gold mining and agribusiness.

Further analysis shows the airstrip overlaps the land claimed by four farms that also partially overlap with each other, including their legal forest reserves and permanent preservation areas, the portion of native vegetation that landowners are required to leave untouched,as mandated by Brazil’s Forest Code.

Like the majority of Brazilian states, Maranhão doesn’t officially disclose information about the individuals who are listed on the CAR land registry, stating privacy concerns over personal information. But data obtained by Mongabay through its network of high-ranking sources reveal the farmers behind the activities.

Most of the airstrip overlaps with the Mangueira ranch, or fazenda, whose CAR was registered in 2015 by Gilberto Holanda dos Santos, a merchant and a target of lawsuits over alleged missed payments to the professional association overseeing his industry. He is also the head of the Council of Evangelical Ministers in the town of Açailândia and ran for town councilor with the Cidadania political party in 2020; Fazenda Mangueira wasn’t included in his asset declaration for the political campaign As set by the Superior Electoral Court, the candidates’ declared goods should include assets in their own name, including houses, apartments, farms, and vehicles. Santos didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment nor presented a defense in the debt collection lawsuit that’s ongoing in a federal court in Imperatriz.

In 2023, Fabricio Lima Gouveia registered a CAR to Fazenda Mangueira, which covers almost exactly the same area as Santos’s farm. A freight transport businessman, Gouveia made a small donation to former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro for his 2022 reelection campaign. In 2021, he also registered a CAR with two other fazendas, Porto Seguro and Nova São Pedro, which overlap the airstrip on the east and west — the central area is occupied by Fazenda Mangueira registered in different CARs by both Santos and Gouveia.

The presence of cattle ranching inside Arariboia, the Guardians say, is also driven by a strategy of co-optation, whereby Indigenous Guajajara are persuaded to rent the land for pasture to non-Indigenous farmers. Image by Ingrid Barros for Mongabay.

In 2022, Gouveia registered another CAR for Fazenda São Pedro and Fazenda Nova, which overlap Fazendas Porto Seguro and Nova São Pedro on the eastern side, covering approximately half of the area of the airstrip.

SEMA says the CAR of Fazenda São Pedro and Fazenda Nova was canceled.

The Maranhão State Public Ministry’s lawsuit against Gouveia for embezzlement, money laundering and corruption originated from a 2017 police report filed by a slaughterhouse, meatpacker, wholesale and retail company of cattle products and byproducts. Gouveia was the manager of the company’s 22 farms, the company said in the lawsuit, adding that an audit found he had engaged in “fraudulent conduct” in livestock deals. In his testimony in the police inquiry, Gouveia denied the accusations, saying that the relocation of animals was carried out under verbal authorization from his employer, adding that his income comes from buying and selling cattle and his transport company. When asked if he’s been in jail, he said he has already been criminally prosecuted in Tocantins state but he has never been arrested.

In 2017, prosecutors said Gouveia used money obtained from fraudulent cattle deals to purchase vehicles and farms, including Fazenda São Pedro and Fazenda Nova — registered under one of his three CARs overlapping the airstrip that was canceled. “It is clear that this practice constitutes a crime of money laundering,” state prosecutor Eduardo André de Aguiar Lopes wrote. Gouveia didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment nor the lawyer representing him in the lawsuit.

In an emailed statement, the national agency for agrarian reform (INCRA) said CAR is self-declaratory and “constitutes an environmental management tool, having no relation to territorial planning,” referring to Mongabay question about the four CARs in the airstrip area overlapping public lands in the SIGEF system. Questions regarding the CAR system, INCRA added, must be forwarded to the system manager, the Brazilian Forest Service. However, CAR registries are commonly used by farmers as an instrument for land ownership claims and also to obtain bank financing to their businesses, as widely reported by prosecutors, activists and the press.

Drone image shows destruction by cattle ranching less than a kilometer (0.6 miles) from the border of the Arariboia Indigenous Territory. Image courtesy of the Ka’aiwar Indigenous Association of Forest Guardians of the Arariboia Indigenous Territory.

‘It’s a real mess’

The headwaters of the Buriticupu River were excluded from Arariboia’s demarcation process. The land around Arariboia, which was allocated to Maranhão state, was later occupied by farms bordering the Indigenous territory, where the river banks have been logged less than a kilometer from Arariboia. “This is land grabbing in our territory,” says forest guardian Olímpio Iwyramu Guajajara.

Brazil’s Forest Code mandates a “marginal strip” of land next to rivers where logging is prohibited, but along Arariboia’s borders the banks of the Buriticupu have been cleared behind a thin line of trees that was left visible in front of the farm.

Drone footage and analysis of satellite imagery show deforestation of 19.4 hectares (48 acres) along the riverbank occurred in July 2023, shortly before our visit in August — a 15.8-hectare (39-acre) patch lies less than a kilometer from the river. Satellite imagery shows some cleared areas as early as 2015, with deforestation intensifying in October 2021 and between May and November 2022.

Mongabay’s analysis shows that an area that was deforested in July 2023 includes land in legal forest reserves and permanent preservation areas, making the logging illegal, in accordance with the Forest Code and the environmental crime law. Further analysis revealed that the illegally deforested area overlaps with the CAR of four farms — an example of Maranhão’s messy land management system, according to prosecutors.

Haroldo Paiva de Brito, a state prosecutor focused on agrarian conflicts in Maranhão, says the state’s land management system is “extremely tumultuous” and its land control system is weak. “The state of Maranhão still has no idea of the amount of land it owns,” he says.

All land in Brazil was publicly held, he explains, but over the years since independence, laws were passed regulating the transfer of land to private ownership.

“So what’s happening today? The state of Maranhão doesn’t know where the vacant lands are, [which are] those that have to be returned to the state,” the prosecutor says. “And it still doesn’t know how its lands ended up in the hands of certain owners.”

“It’s a real mess,” he adds.

Mongabay’s analysis shows that areas deforested in 2023 include land in legal forest reserves and permanent preservation areas, making the logging illegal under the Forest Code and the environmental crime law. Image courtesy of the Ka’aiwar Indigenous Association of Forest Guardians of the Arariboia Indigenous Territory.

Logged wood in the Arariboia Indigenous Territory. Image courtesy of the Ka’aiwar Indigenous Association of Forest Guardians of the Arariboia Indigenous Territory.

One of the farms encroaching on Arariboia’s borders is Fazenda Bezerra, whose CAR was registered by Francisco Alves Ferreira, known as Assis, who was arrested for illegal possession of a firearm in 2022, according to local news reports, and was sued for squatting and land grabbing that same year. The lawsuit, which is ongoing in a state court in Amarante, included claims by a neighbor accusing Ferreira of invading his farm and selling it to third parties without his authorization. In his testimony in June 2023, Ferreira denied the accusations, saying that he doesn’t know the author of the complaint and that he has never worked with the sale or subdivision of land.

The neighboring farmer also reported that Ferreira hired a topographer to georeference the land and regularize its ownership with Maranhão state, claiming that the land was vacant. Five plots were reportedly registered under Ferreira’s relatives’ names, and the caretaker of the neighbor’s farm, who lived in the area, reportedly said he felt threatened by Ferreira’s actions. In his testimony, Ferreira said that he knows the topographer and has already hired him to take measurements on his farms, but none of them border the claimant’s land. He said he owns three farms, including Fazenda do Bezerra — where we found illegal deforestation on the Buriticupu river banks — and none of them are documented. Ferreira didn’t respond to Mongabay several requests for comment.

Fazenda Bezerra’s CAR record almost completely overlaps with Fazenda Boa Esperança’s CAR, registered by Arnom Nascimento Ferreira, Francisco’s son. Fazenda Boa Esperança has no title deeds and can’t be sold, donated or used as collateral, according to data from the federal land management system, SIGEF. Arnom didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment.

The CARs of these two farms also overlap with another Fazenda Bezerra, whose CAR was registered by Adirceu Alves da Silva, which was embargoed by IBAMA in 2018 for illegal deforestation. Silva is also being sued by the Maranhão Federal Public Ministry for crimes against the environment, genetic heritage and flora. In his testimony in December 2019, Silva said he has not committed any environmental crimes on his property and the deforestation in question occurred before he bought the farm about five years ago. The farmer said that IBAMA was at his farm and asked him to lower the height of the weir, which he did.

The criminal lawsuit originated from 2018 anonymous claims filed on behalf of Guajajara leaders about the devastation of a permanent preservation area on the banks of the Buriticupu river headwaters close to Amarante. After several delays in the diligencies requested by the Federal Public Ministry in Imperatriz since 2018, in October 2022 the Federal Police carried out an aerial survey ratifying the destruction of native vegetation on the river banks source in two different locations.

In September 2023, federal prosecutor Thomaz Muylaert de Carvalho Britto denounced Silva criminally for damaging the permanent preservation area “with free and conscious will” building a dam at the Buriticupu River source for an irrigation system for corn and watermelon plantations. The prosecutor said the farmer’s conduct “fits perfectly with the criminal offense” provided by the Environmental Crimes Law for “destroying a river spring without a license or authorization from the competent authority.” Silva didn’t respond to Mongabay several requests for comment. The criminal suit is ongoing in a federal court in Imperatriz.

The fourth farm, Fazenda Campo Verde, whose CAR was registered by Antônio José Alves de Sousa, covers part of the Governador Indigenous Territory. Sousa has rented a property in Maranhão to Funai since 2014 with a waiver of tender, totalling $30,000 in the 10-year period. The property hosts the headquarters of Funai’s local branch in Amarante. Since 2015, Sousa has also rented out a property to the regional electoral court in Amarante. Sousa didn’t respond to several Mongabay requests for comment.

In an emailed statement to Mongabay, Funai said it follows all bidding procedures set by Federal Attorney General’s Office for rental contracts, adding that the current requirements don’t include research into environmental crimes nor a negative certificate to this effect “making it impossible to research and/or disqualify a supplier” when it fulfills all the current criteria. Funai didn’t mention any measures to adopt after being acknowledged of Mongabay findings.

In an emailed statement, the electoral court in Amarante said the lease contract with Sousa is “in order, with no pending issues formalized to date,” has been extended and runs until October 2024.

[if lt IE 9]><![endif]</p>