By Timothy J. Killeen

Vale SA

Brazil’s second most valuable company is also the fifth largest global mining corporation. In 2022, it was as ranked by the Refinitiv ESG framework as best in its class of ‘diversified miners’ (1 out of 615). This score is remarkable considering Vale is being sued by the SEC for deliberately misleading investors of its ESG-related risks prior to the tailings pond disasters at Brumadinho in 2019. Ironically, this high ranking is a direct consequence of that disaster, which led to a 50 % drop in its share price and the dismissal of its CEO. The company subsequently invested in multiple high-profile ESG initiatives, particularly the enhanced monitoring of tailing storage facilities, accelerated remediation of environmental liabilities and the creation of compensation programmes for communities impacted by its operations.

Vale operates the world’s second largest iron ore mine in the Carajás district of south-central Pará. Even before Brumadinho, ESG concerns had motivated the company to develop a dry-tailings management system at the S11D iron ore mine at the Carajás Serra Sur complex. Other sustainability-linked features at the site include a spatial layout that placed 97 % of its industrial facilities in previously deforested pasture outside the forest reserve where the mining concessions are located. Industrial innovations include an ore-hauling system that eliminates the use of diesel-powered trucks, which reduces carbon emission by ~50 %. According to corporate reports, the S11D mine is a template for how Vale will meet its commitment to be net carbon zero by 2050.

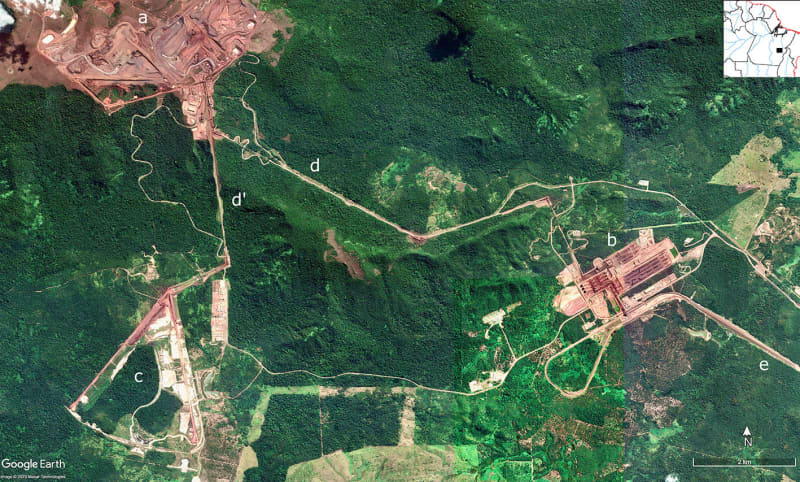

Brazil’s largest privately held company, Vale SA, operates the Carajás Serra Sur iron ore mining complex, which is located within the Carajás National Forest. The company started operations in 2016 at the S11D pit mine (a), which is part of an integrated system that eliminates the use of trucks to move ore to the processing mill (b) and a dry tailings management system (c). Ore and waste rock are moved via conveyer belts (d and d’), while concentrated iron ore is moved to the export terminal via the Estrada de Ferro Carajás. The company presents the Carajás Serra Sur mining complex as an example of responsible mining based on the principals of ESG investing, in part because of reduced GHG emissions and the elimination of water-based tailing management systems. Data source: Vale SA.

As part of its broader ESG strategy, Vale is implementing water-conservation strategies and investing in renewable energy across all its operations. This includes purchasing electricity from the controversial Belo Monte hydroelectric dam on the Rio Xingu and the Estreito hydrodam on the Rio Tocantins. There are no plans to abandon water-dependent tailing management systems or the truck-based ore hauling systems at iron ore pits at Carajás Serra Norte or the copper mines at Salobo and Sossego (Annex 5.1). The company inspected all its tailing dams and reported engineering flaws at only one site in the Carajás mining district: an abandoned gold mine known as Igarapé Bahia that was subsequently decommissioned and de-characterized in 2021. Other environmental actions taken by the company include the conservation of one million hectares of native forest, which it manages in coordination with the Brazilian national park service (ICMBio), and a commitment to assist local landholders reforest 100,000 hectares of degraded pasture by 2030.

Social controversies accompanied the recent US$1.5 billion expansion of the company’s 1,000-kilometre railway, which runs adjacent to Awá, Guajajara and Ka’apor Indigenous communities in Maranhão. Accusation of water pollution at the Onça Puma nickel mine led to legal action on behalf of the Kayapo ethnic group. Vale has responded to these and other complaints with a legal strategy that denies liability, while negotiating compensation agreements with the aggrieved parties.

Vale holds the right to explore for minerals in hundreds of concessions acquired via public auctions over several decades. In many cases, their below-ground mineral rights overlapped with above-ground rights of formally constituted indigenous territories. This contradiction became a serious public relations problem when the Bolsonaro administration attempted to weaken the legal protection of Indigenous lands. In 2021, Vale formally relinquished its rights to any concession that overlapped with Indigenous lands and reaffirmed its commitment to the concept of FPIC.

Mineração do Rio Norte (MNR)

A sustainability initiative that predates ESG investing is the restoration of rainforest habitat at the Trombetas bauxite mine in Oriximiná, Pará, which is operated by MNR, a joint venture between Vale and four other companies: South32, Rio Tinto, Companhia Brasileira de Alumínio and Norsk Hydro (5%). The consortium has avoided much of the controversy surrounding the Carajás mine by committing to an ambitious forest-restoration project. Over the past four decades, MNR has restored ~7,000 hectares of land reclaimed from a massive strip mine that has consumed ~15,000 hectares of natural rainforest habitat. The mine is scheduled to cease operations in 2025 and presumably will eventually restore about 75 per cent of the total impacted area.

Other claims to sustainability include an industrial mill that recycles eighty per cent of its water-use and tailings management protocols via a concatenated series of ponds covering ~1,300 hectares. Individual ponds have been designed to be de-watered and decommissioned as the mine ages; however, it is unlikely any of the ponds will be amenable to the cultivation of trees, much less the restoration of a natural habitat. Following the Brumadinho tragedy, the company reviewed their containment dams and reported that all were structurally sound and designed to withstand a 10,000-year rain-event. If they were to fail, they would impact adjacent natural forest habitat but not pose a threat to nearby communities.

Mineração Taboca SA

The Pitinga mine, owned by Mineração Taboca SA, in Amazonas state exploits the richest tin deposit in the world. It operated as a subsidiary of the Paranapanema Group from 1979 to 2009, when it was acquired by Minsur SA, a medium-sized company that runs several polymetallic mines in the Peruvian Andes. Minsur adheres to international sustainability standards and provides a relatively detailed overview of its practices in its annual reports. The company is large enough to warrant the attention of the ESG rating agencies with scores that reflect its efforts to report and monitor its environmental and social impacts of its Peruvian operations (157 out of 615). However, these scores may not accurately reflect the very significant environmental and social liabilities of the Pitinga mine.

The mine was operated for the first three decades using placer mining technologies that destroyed thousands of hectares of riparian forest on land that once belonged to the Waimiri–Atroari Indigenous nation. This iconic Indigenous tribe survived a genocidal attack by the military in the 1960s only to be dispossessed of a third of their territory by the mining concessions granted to Mineração Taboca (see 11). Following its purchase, Minsur abandoned placer mining operations and shifted production to an open-pit hard-rock mine. Rather than remediate the legacy tailings and isolate the tailings produced from the open pit, the new owners converted the abandoned placer mines into an ad hoc water-treatment facility. The abandoned placer mines/tailing ponds are located on the headwaters of the Rio Alaluá watershed, which drain westward into Indigenous lands.

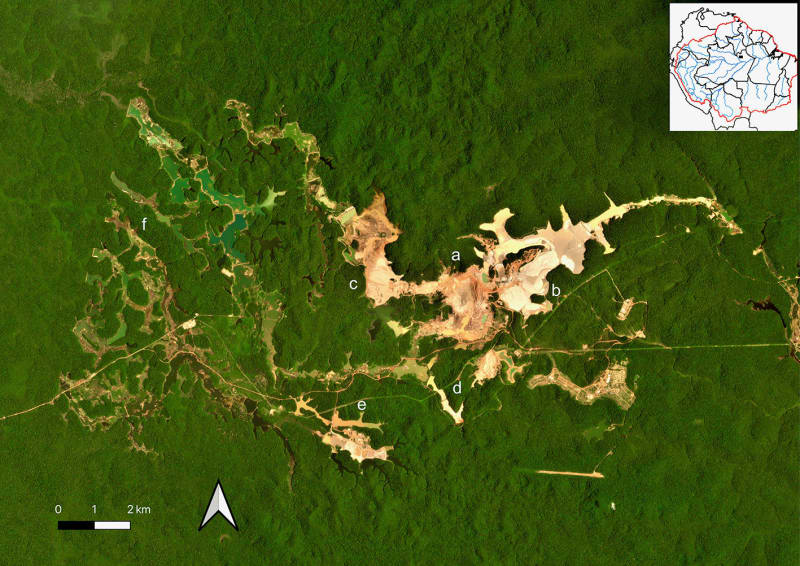

The tailing ponds at the Pitanga cassiterite mine in Amazonas are the legacy of placer and open-pit mining operations spanning five decades. The current operator, Minsur SA of Peru, purchased the mine in 2005 and assumed legal responsibility for their remediation and, eventually, decommission. Key: Open pit mine (a) and large tailing pond (b) that drains east towards the Balbina reservoir. Tailing ponds associated with secondary pits and mill facilities (c, d, e) that drain into catchment reservoirs occupying legacy placer riverscapes (f) situated upstream from the the Waimiri-Atroari Indigenous Territory. Source: Planet Labs Inc.

The Waimiri–Atroari have filed complaints with environmental authorities questioning the efficacy of the tailings management regime and have provided factual evidence of leaks of noxious substances. The company has responded by attesting to the structural integrity of fifteen dams that are the major components of its waste-management system, which channels water through a concatenated series of ponds with decreasing levels of suspended sediments. Satellite images show there are at least sixty interconnected ponds covering more than two thousand hectares, all of which are located in floodplains that were previously destroyed by placer mines. Presumably, when the Pitinga mine is closed, 25 years in the future, all these ponds will be dewatered, decommissioned and de-characterized.

Potássio do Brasil Ltd.

Potássio do Brasil Ltd. touts its ESG credentials by asserting that its future operations will displace carbon-intensive fertilizer imports from Russia, Belarus and Canada. The company, which is incorporated in Brazil, is the creation of Forbes and Manhattan, a Canadian investment bank that provides venture capital to greenfield-mining enterprises. If successful, the promoters will open an industrial-scale potash mine at Autazes near the junction of the Madeira and Amazon rivers.

The domestic potash mine’s environmental benefits are largely based on estimates of GHG-emission reductions achieved by replacing fertilizer imports from fossil-fuel-based production systems with fertilizer manufactured using the Amazon’s abundant hydropower energy. These GHG reductions, which are significant, would be augmented by reductions from decreased transportation emissions and the displacement of diesel-based generators used by local communities because of the expansion of the regional electrical grid.

Opponents object on environmental and social grounds arguing the mine site is on an ecologically fragile area (Amazon floodplain) and would impact nearby Indigenous and ribeirinho villages. The company claims the spatial footprint will be minimized because tailings will be returned to underground shafts and water will be recycled to reduce impacts to floodplain habitats. A major point of contention is agreements with local communities. The company maintains it has complied with Brazilian regulations by obtaining the consent of individual communities, but Indigenous organizations maintain that consent was not obtained via an open and informed process. The company has not chosen, apparently, to participate in any of the ESG evaluation initiatives despite its ostentatious claims of incorporating ESG principles into the heart of its proposed development strategy.

The tailing ponds at the Pitanga cassiterite mine in Amazonas are the legacy of placer and open-pit mining operations spanning five decades. The current operator, Minsur SA of Peru, purchased the mine in 2005 and assumed legal responsibility for their remediation and, eventually, decommission. Key: Open pit mine (a) and large tailing pond (b) that drains east towards the Balbina reservoir. Tailing ponds associated with secondary pits and mill facilities (c, d, e) that drain into catchment reservoirs occupying legacy placer riverscapes (f) situated upstream from the the Waimiri-Atroari Indigenous Territory. Source: RAISG (2022).

Aço Verde do Brasil (Grupo Ferroeste)

The world’s first producer of ‘green steel’ is the family-owned company, Aço Verde do Brasil, which uses biomass as a source of thermal energy and charcoal as a reducing agent in the steel-making process. The company’s steel mill is located in Açailândia (Maranhão) and sources its biomass charcoal from 15,000 hectares of eucalyptus plantations located in surrounding municipalities. The company was awarded the ESG Breakthrough Award (Global Metals Category) at the S&P Global Platts conference in 2021 in recognition of its production of steel with (almost) zero GHG emissions. Aço Verde, which translates as ‘green steel’ comercializes a variety of steel with a GHG footprint of 0.02 tonnes CO2 per tonne of steel compared to a conventional coal-powered plant with 1.85 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel.

While billed as pioneer accomplishment, the use of biomass charcoal by the metallurgical industry in Brazil has been commonplace for decades, particularly at pig-iron mills that concentrate raw iron ore into cast-iron ingots. In the last half of the twentieth century, the conversion of ‘waste wood’ into charcoal for steel companies was an important revenue stream for landholders who were clearing natural forest to create cattle ranches. This quasi-legal market ended in 2005 when government policies led to a dramatic reduction in deforestation and forced companies to switch energy feedstocks into a mixture of coal and cultivated biomass.

Aço Verde’s corporate predecessor (Gusa Nordeste) was a major consumer of deforestation charcoal, but the parent company (Grupo Ferroeste) foresaw the end of uncontrolled deforestation and started planting eucalyptus plantations as early as 1993. The steel mill and its associated plantations are located in a heavily deforested municipality where less than 30 % of the original natural forest is conserved. Nonetheless, the company attests that all charcoal feedstock originates on landholdings with ~40 % natural forest, and that all providers comply with the Codigo Florestal and the required allotment of Area Permanente de Preservação (APP). The company also reports an impressive portfolio of community-development programmes in sports, health and education, including the establishment of a technical school in the industrial arts.

Newmont Corporation

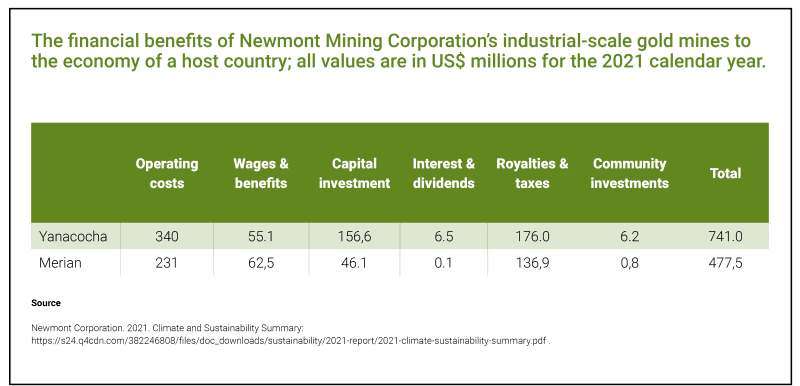

The world’s largest gold miner, Newmont Corporation, operates two industrial-scale mines in the Pan Amazon: Yanacocha in Cajamarca, Peru and Merian in the Sipilwini District of Suriname. Newmont is domiciled in the United States and has an ESG ranking of five (of 615) in the class of diversified miners and seven (of 120) in the class of miners of precious metals. It has leveraged its exalted ESG status by issuing a US$1 billion ‘green’ bond that will pay a premium interest rate if the company fails to track an explicit pathway of GHG reductions: ~30 % reduction by 2030.

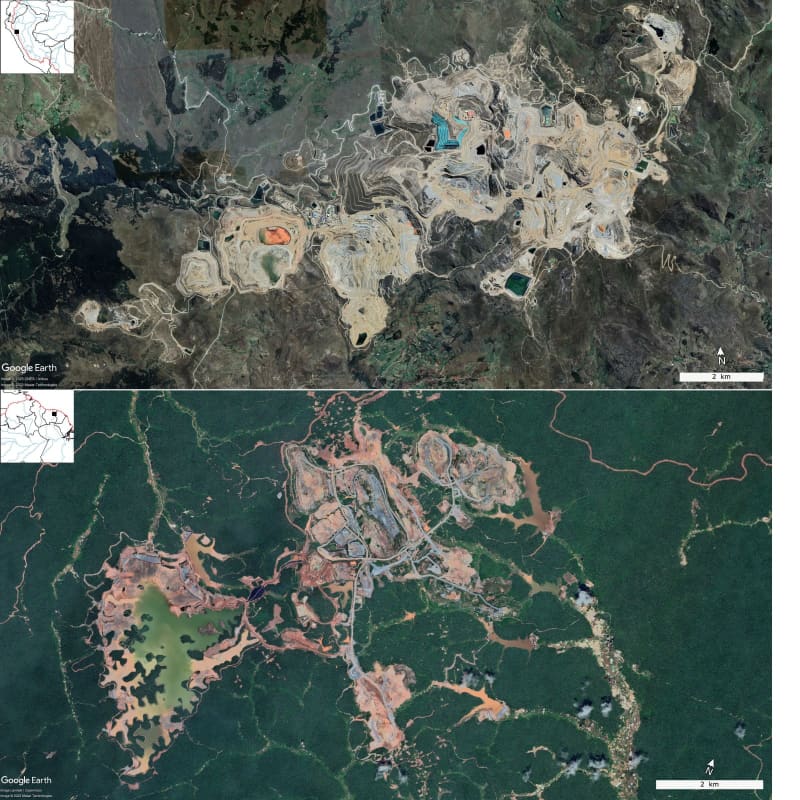

The Yanacocha mine is a sprawling multi-pit complex spanning more than 5,000 hectares in the semi-arid highlands of the Central Andes. It was opened in 1993 and suspended operations in 2022. The mine site is notable for the absence of tailing ponds, a consequence of the heap-leach technology used to extract gold. The Merian mine was opened in 2016 and covers only ~500 hectares; however, it is surrounded by catchment ponds covering an additional 1,000 hectares, which reflect the tank-leaching technology used at high-rainfall industrial mills. Despite the differences in technology, both mines adhere to international standards regarding cyanide management; the company reports it recycles ~77 % of the water used in its processing plants.

Both mines are essentially money machines, and they provide considerable economic benefits to their host countries. As a high-profile gold miner, Newmont is particularly attuned to the reputational risk associated with social conflict and, in keeping with its ESG commitments, allocates significant resources to community development. Nonetheless, it occasionally needs to be reminded of the limits of its power.

In 2016, the company abandoned more than a decade of planning to extend the lifetime of the Yanacocha complex; known as the Conga Project, the company had plans to excavate a series of open-pit mines on an adjacent mountain. These plans were derailed by a subsistence farmer, Máxima Acuña de Chaupe, who refused to surrender her small family farm to the mining giant and its powerful Peruvian partner (Compañía de Minas Buenaventura).

Newmont’s subsidiary company forcefully evicted her family and took her to court for illegally squatting on her own land. Ms Acuña was found guilty, received a ‘suspended’ prison sentence and was fined US$2,000. The Peruvian Supreme Court overturned her sentence and restored her property rights. This lesson in humility cost the company at least US$1 billion and disrupted an investment valued at US$12 billion. It also showed why a properly executed consultation process (FPIC) is in the best interest of a mining corporation, because it will protect the company from the incompetence and malfeasance of its own employees, or in this case, business partner.

Newmont Corporation operates two massive gold mines in the Amazon. Top: The ~5,000 hectare complex at Yanacocha in the semi-arid Andes near Cajamarca, Peru, uses a cyanide heap-leach technology to concentrate gold. Instead of large-scale tailings ponds, the complex has a dozen smaller cyanide recycling ponds that are situated adjacent to heap-leach pads. Bottom: The Merian mine in Suriname spans about 2,000 hectares and includes a 750 hectare tailings pond required by the cyanide tank-leach technology. In addition, the company has constructed five catchment reservoirs to isolate the mine from the surrounding watershed. Data source: Newmont Mining.

Eneva SA

The fastest growing diversified energy company in Brazil, Eneva SA, is seeking to access ESG financial markets by offering solutions to support the energy transition. It has a growing portfolio of solar projects, but most of its revenues are derived from assets that rely on coal, gas and hydropower. In the Amazon, it generates revenues via a ‘reservoir to wire’ supply chain that converts natural gas from proprietary wells into electricity generated at its own utility plants; it commercializes the electricity directly to retail and industrial consumers through the public power grid. This strategy is complemented by liquified natural-gas (LNG) technology to connect isolated gas fields with urban and industrial markets not yet integrated into pipeline networks.

In the last five years, Eneva has acquired six energy assets in the Brazilian Amazon, including the Paranaíba energy complex in Maranhão (Santo Antônio dos Lopes), the Azulão gas field in Eastern Amazonas (Silves) and the Juruá development concessions in the Solimões basin in central Amazonas (Tefé). In February 2022, it inaugurated the Jaguatirica-II power plant in Roraima (Boa Vista), which is supplied with LNG from the Azulão gas field.

Eneva’s investment in LNG transport systems is a first for Brazil, which imports LNG to meet energy demand when the county’s hydropower resources are stressed during periodic droughts. Viewed from this perspective, the natural gas assets of the central Amazon are an increasingly valuable asset, which explains the company’s acquisition of the Juruá concession in 2020. The Juruá concession has an estimated 700 billion cubic feet of natural gas that was discovered by Petrobras in the 1990s.

“A Perfect Storm in the Amazon” is a book by Timothy Killeen and contains the author’s viewpoints and analysis. The second edition was published by The White Horse in 2021, under the terms of a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0 license).

To read earlier chapters of the book, find Chapter One here, Chapter Two here, Chapter Three here and Chapter Four here.

Chapter 5. Mineral commodities: a small footprint, a large impact and a great deal of money

- Mineral commodities: the wealth that generates most impacts in the Pan Amazon | Introduction March 21st, 2024

- The environmental and social liabilities of the extractive sector March 26th, 2024

- Mining in the Pan Amazon in pursuit of the world’s most precious metal April 4th, 2024

- Illegal mining in the Pan Amazon: an ecological disaster for floodplains and local communities April, 9th

- The environmental mismanagement of enduring oil industry impacts in the Pan Amazon April, 17th

- Outdated infrastructure and oil spills: the cases of Colombia, Peru and Ecuador April, 25th

- State management and regulation of extractive industries in the Pan Amazon May 2nd, 2024

- Is the extractive sector really favorable for the Pan Amazon’s economy? May 8th, 2024

- Extractive industries look at degraded land to avoid further deforestation in the Pan Amazon May 15th, 2024

- Global markets and their effects on resource exploitation in the Pan Amazon May 21st, 2024

- Sustainability in the extractive industries is a paradox May 29th, 2024

- In the Pan Amazon, environmental liabilities of old mining have become economic liabilities June 5th, 2024

- Solutions to avoid loss of environmental, social and governance investment June 12th, 2024

This article was originally published on Mongabay