Our nervous system is intricately designed to sense and respond to fear, a crucial survival mechanism. Fear helps us stay vigilant and avoid potential dangers, whether it’s the unsettling sounds we hear alone at night or the imminent threat of a growling animal. However, when fear manifests in the absence of real danger, it can severely impact our well-being. This phenomenon, known as fear generalization, often plagues individuals who have experienced severe stress or trauma, leading to conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Despite its prevalence, the underlying mechanisms of generalized fear have remained largely elusive.

A team of neurobiologists at the University of California San Diego, led by former Assistant Project Scientist Hui-quan Li and Distinguished Professor Nick Spitzer, has made significant strides in understanding these mechanisms. Their study, published in the journal Science, reveals the biochemical changes and neural circuitry involved in stress-induced generalized fear. This research not only sheds light on how fear responses are triggered but also opens up new avenues for potential interventions.

The primary motivation behind this study was to uncover the cellular and circuit mechanisms responsible for fear generalization. While fear responses are essential for survival, they can become detrimental when generalized to non-threatening situations. Such maladaptive fear responses are common in various stress-related disorders, including PTSD. The researchers aimed to identify the specific neurotransmitters and neural circuits involved in this process, hoping to pave the way for targeted treatments that could mitigate the harmful effects of generalized fear.

The researchers conducted their study using mice, focusing on a region of the brain known as the dorsal raphe, located in the brainstem. This area plays a crucial role in regulating fear responses. The team examined how acute stress affected neurotransmitter signals within neurons in this region, particularly focusing on a switch from excitatory neurotransmitters (glutamate) to inhibitory ones (GABA).

To induce stress, the mice were subjected to footshocks of varying intensities. The researchers then measured the mice’s fear responses in different contexts. Specifically, they observed the amount of time the mice spent “freezing,” a common fear response, in both the original context where the shock was administered and a new, different context. This allowed them to distinguish between conditioned fear (specific to the original context) and generalized fear (extending to the new context).

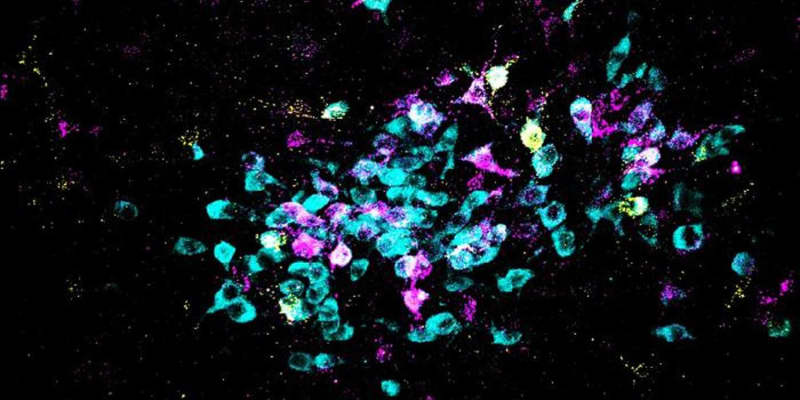

The team also employed advanced techniques to track changes in neurotransmitter expression within the dorsal raphe neurons. This involved immunostaining to identify the presence of specific neurotransmitters and their synthetic enzymes. Additionally, they utilized genetic tools to manipulate neurotransmitter synthesis, enabling them to assess the impact of these changes on fear responses.

The study revealed that strong footshocks led to generalized fear responses in mice. This was accompanied by a notable switch in the neurotransmitter signals within the dorsal raphe neurons, from glutamate to GABA. Specifically, neurons that initially co-expressed glutamate began to co-express GABA instead, a change that persisted for several weeks.

Further investigations showed that this neurotransmitter switch was critical for the development of generalized fear. When the researchers used genetic tools to suppress the synthesis of GABA in the dorsal raphe neurons, the mice did not exhibit generalized fear, even after experiencing strong footshocks. This finding underscores the pivotal role of the glutamate-to-GABA switch in mediating stress-induced fear generalization.

“Our results provide important insights into the mechanisms involved in fear generalization,” said Spitzer, a member of UC San Diego’s Department of Neurobiology and Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind. “The benefit of understanding these processes at this level of molecular detail — what is going on and where it’s going on — allows an intervention that is specific to the mechanism that drives related disorders.”

Building on their findings in mice, the researchers examined postmortem brain samples from individuals who had suffered from PTSD. They discovered a similar switch from glutamate to GABA in the dorsal raphe neurons of these individuals, suggesting that the mechanisms observed in mice are relevant to human PTSD.

The team also explored potential interventions to prevent the development of generalized fear. They found that administering an adeno-associated virus (AAV) to suppress the gene responsible for GABA synthesis in the dorsal raphe before the experience of acute stress effectively prevented generalized fear in mice. Additionally, treating mice with the antidepressant fluoxetine (commonly known as Prozac) immediately after a stressful event also prevented the neurotransmitter switch and the subsequent onset of generalized fear.

While the study provides valuable insights, it also has limitations. The research was primarily conducted on mice, and although similar mechanisms were observed in human PTSD samples, further studies are needed to confirm these findings. Additionally, the long-term effects of manipulating neurotransmitter synthesis and the potential side effects of such interventions require further investigation.

Future research could explore the broader implications of these findings. For instance, understanding whether similar neurotransmitter switches occur in response to other forms of stress, such as psychological stress, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of fear generalization. Moreover, investigating the specific neural circuits downstream of the dorsal raphe that mediate generalized fear responses could lead to more targeted and effective treatments.

“Now that we have a handle on the core of the mechanism by which stress-induced fear happens and the circuitry that implements this fear, interventions can be targeted and specific,” said Spitzer.

The study, “Generalized fear following acute stress is caused by change in co-transmitter identity of serotonergic neurons,” was authored by Hui-quan Li, Wuji Jiang, Lily Ling, Vaidehi Gupta, Cong Chen, Marta Pratelli, Swetha K. Godavarthi, and Nicholas C. Spitzer.