Researchers have found that people with difficult-to-treat major depressive disorder who show lower activation of the amygdala — a part of the brain involved in processing emotions — when viewing sad versus happy faces are less likely to experience improvement in their depressive symptoms after four months of standard treatment. This discovery, published in the journal Psychological Medicine, could help in developing personalized treatment plans for patients with depression by identifying those less likely to respond to conventional therapies.

Only about half of patients with depression respond to their initial treatment, and even fewer achieve remission. This low success rate underscores the need for better ways to predict treatment outcomes, which could facilitate personalized treatment plans. A group of research, led by Diede Fennema, aimed to find reliable markers that could predict how well a patient would respond to standard depression treatments.

They focused on the brain’s response to emotional stimuli, building on the understanding that people with depression often process negative emotions more strongly than positive ones. The study’s methodology involved examining the brain responses of individuals with difficult-to-treat depression to emotional stimuli using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

“Recording functional MRI signal whilst seeing pictures of facial expressions of emotions has been used widely to detect an unconscious bias towards negative versus positive emotional stimuli in anxious individuals with and without depression,” explained senior author Roland Zahn, a professor of mood disorders and cognitive neuroscience at King’s College London.

“Most of these studies, however, were not pre-registered or were carried out in patients who had been selected for clinical trials or specialist settings with very specific inclusion criteria such as having to be free of medication. This means it was unclear whether these results would also apply to people seen clinically by GPs in the United Kingdom where most people with depression are treated.”

“Pre-registration (i.e. publishing the details of how one is going to analyse one’s data on an open database) is important as it increases the likelihood of reproducible findings that could be used clinically. We had therefore pre-registered our analysis plan and were able to recruit a sample of people with difficult-to-treat major depression who are typical of those receiving primary care in the United Kingdom, often taking an antidepressant medication.”

The participants included 38 adults aged 18 or older, all experiencing a current major depressive episode and who had not benefited from at least two different serotonergic antidepressants. Participants were recruited from an existing trial on antidepressant treatments and through online advertisements.

The researchers used a backward masking task during the fMRI scans to present emotional stimuli. In this task, participants were shown pairs of facial expressions, where a target face displaying a sad, happy, or neutral emotion was quickly followed by a neutral face. This method ensured that the target face was presented subliminally, meaning the participants were not consciously aware of it. The task was designed to measure the participants’ neural responses to these emotional stimuli without their explicit awareness.

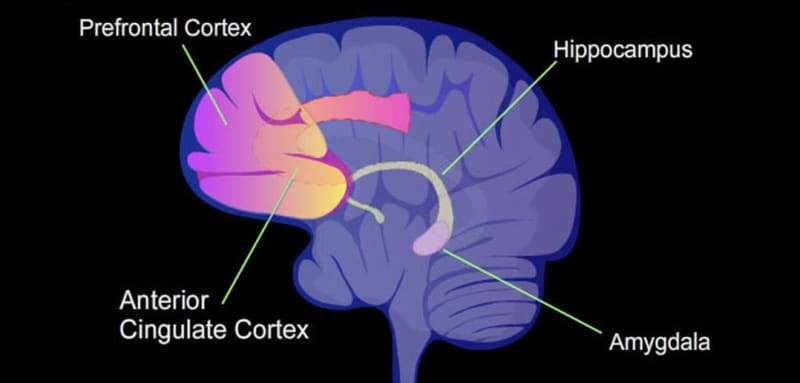

The study found that lower bilateral amygdala activation in response to sad faces compared to happy faces predicted poorer clinical outcomes. Participants with a weaker amygdala response to positive emotions were less likely to see an improvement in their depressive symptoms after four months of standard treatment.

This finding suggests that the brain’s ability to process positive emotions may be crucial for recovery in patients with difficult-to-treat depression. The effect was particularly notable in the right amygdala, indicating that this hemisphere might play a more significant role in the subliminal processing of emotional stimuli.

“We confirmed our prediction based on previous research that people with a weaker amygdala response to positive relative to negative facial expressions were less likely to improve their depressive symptoms after four months,” Zahn told PsyPost.

Interestingly, participants who showed a greater improvement in their depressive symptoms had stronger amygdala responses to happy faces. This pattern suggests that a positive emotional processing bias—potentially facilitated by treatment—may be linked to better clinical outcomes. The researchers proposed that treatments that enhance the brain’s response to positive stimuli could be beneficial for individuals with depression.

The study also examined the activation of the dorsal/pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, another brain region associated with emotional processing. However, they found no significant association between activation in this region and treatment outcomes. This result contrasts with some previous studies and may be due to differences in the sample population and study design.

While the study’s findings are promising, there are several limitations. The sample size was relatively small, which limits the power of the study to detect significant effects. Additionally, the participants were taking a variety of antidepressant medications, which could introduce variability in the observed brain responses. Future research should aim to replicate these findings in larger and more homogenous samples.

Additionally, exploring the role of co-morbid anxiety in modulating brain responses to emotional stimuli could provide further insights. The researchers suggest that enhancing amygdala responses to positive stimuli could be a potential target for new treatment approaches.

“Dr. Diede Fennema has submitted another paper where she combines different fMRI measures to show how together these get much closer to making individual predictions, although not quite,” Zahn added. “Overall, her PhD work shows that by using reproducible functional MRI signatures of negative perceptual biases, self-blaming biases and resting-state fMRI changes, one can detect that individuals with depression differ and that for some people one neural system is more relevant than for the other. This will help us to design better treatments such as specific brain training methods tailored to the individual.”

The study, “Neural responses to facial emotions and subsequent clinical outcomes in difficult-to-treat depression,” was authored by Diede Fennema, Gareth J. Barker, Owen O’Daly, Suqian Duan, Beata R. Godlewska, Kimberley Goldsmith, Allan H. Young, Jorge Moll, and Roland Zahn.