Islam empowers Muslim women.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) was the world’s first feminist.

Women are highly revered and granted fundamental rights by Islam.

I’ve encountered variations of these statements throughout my decade-long study of Muslim feminism, but they were rarely accompanied by a thorough list and explanation of the rights they refer to — until now.

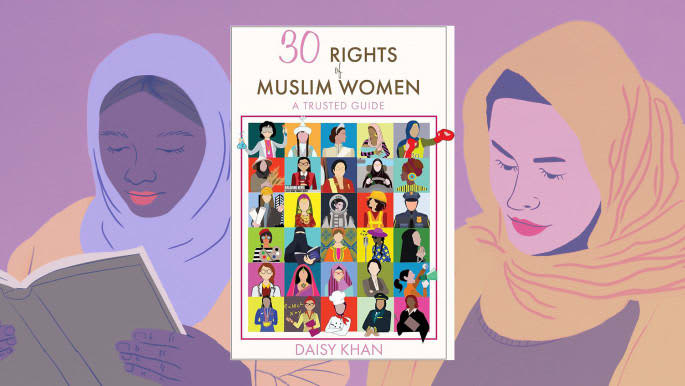

Daisy Khan’s 30 Rights of Muslim Women: A Trusted Guide provides a compact yet comprehensive list of rights granted to Muslim women by the Quran and Hadith.

Grounded in these Islamic sources, Khan categorises the rights under the six objectives of Shariah, ensuring the framework is rooted in faith while exploring themes often considered “feminist.”

She covers everything from family to spirituality — rights to maturely choose marriage, divorce, care for orphans through motherhood, access to religious spaces, and participate in religious and spiritual leadership as jurists and interpreters of Islamic texts.

“This book is like a toolkit for women to fight their own battles, because I cannot go to every corner of the world to do this”

Imam Dr Mohamed Jebara called the book “an encyclopaedic reference to the most pressing of topics.”

“I’ve been writing this in my head since September 11, 2001,” Khan tells me over Zoom. She wears a bright red blouse with a gold crescent pendant — matching the one I happen to be wearing.

“I wrote it for people like you in mind – literally. In my mind were images of women all over the world who are passionate about their faith, but this is the missing piece.”

For American Muslims, Khan is a household name in discussions about progressive Islam, Muslim women’s activism, and interfaith initiatives.

In 1997, she and her former husband, Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, established the American Society for Muslim Advancement (ASMA).

In 2004, she founded Muslim Leaders of Tomorrow (MLT)%20is%20a%20global%20program,generation%20of%20young%20Muslim%20leaders.), and in 2006, she launched the Women’s Islamic Initiative in Spirituality and Equality (WISE).

Throughout her various projects and initiatives, Khan has been vocal about issues like domestic violence, honour killings, female genital mutilation, and other culturally influenced injustices that have no basis in religion.

Her work has taken her from America to places like Egypt and Afghanistan, where she has emphasised the importance of girls' education.

30 Rights of Muslim Women marks a new phase in Khan’s activism — sharing her work so it can be absorbed and implemented by Muslim women and their allies everywhere.

“Re-educating the imams and women about their rights is where the work needs to be,” she says.

“This book is like a toolkit for women to fight their own battles because I cannot go to every corner of the world to do this.”

“The battle fought by Muslim feminists is two-fold — on one hand, there are Islamophobes who insist Islam oppresses women, an idea fuelled by mainstream Western media. On the other hand, there are zealous extremists who mistake cultural misogyny for religious practice”

Khan recalls a childhood memory where her father gave her, the youngest of three daughters, a pair of boxing gloves, encouraging her to learn self-defence while also boosting her confidence.

“They’ve almost become a metaphor — the gloves are invisible now, but the arena is always there. This book is like my boxing glove. It’s a shield against oppression, but it’s also a hammer against injustice,” she explains.

The battle fought by Muslim feminists is two-fold — on one hand, there are Islamophobes who insist Islam oppresses women, an idea fuelled by mainstream Western media.

On the other hand, there are zealous extremists who mistake cultural misogyny for religious practice.

These “limiting beliefs of some Muslims” are to blame for women’s rights being denied and their roles being restricted to marriage and motherhood, says Khan.

But women in early Islam were teachers, healers, fighters, and martyrs. “They issued decrees; they debated as equals. If all that was happening during the time of revelation, where is the disconnect? Why are we not living up to the Prophet’s example and to what God decreed?

“As I was writing this book, I discovered that I felt very comfortable in 7th-century Arabia — it was a progressive time,” Khan adds.

“Women were central to developing and propagating Islam and were playing all the roles we now consider modern.”

Throughout the book, Khan mentions both prolific women of early Islam and modern-day entrepreneurs, politicians, and activists, highlighting an inspiring legacy of Muslim women’s empowerment.

“The book brings life to the ancient women while also honouring those who are in the arena right now,” she explains.

Throughout the book — which Khan says does not need to be read chronologically — she debunks many myths, one being the belief that the Prophet’s wife Aisha was a minor when she was wed.

“If people can take away one thing from this book — just remember, she was not nine years old; she was an adult,” says Khan.

And while the book is now published, the work remains ongoing.

Khan aims to introduce the book to markets in the Middle East and Asia. She plans to organise webinars and workshops, with training presentations already prepared for each of the 30 rights, some extending up to 60 slides in length.

Now, she hopes to pass on her proverbial boxing gloves to Muslim women — activists, lawyers, human rights practitioners, and allies — who strive to conquer the cultural attitudes that often prevent them from enjoying their divinely ordained rights.

Hafsa Lodi is an American-Muslim journalist who has been covering fashion and culture in the Middle East for more than a decade. Her work has appeared in The Independent, Refinery29, Business Insider, Teen Vogue, Vogue Arabia, The National, Luxury, Mojeh, Grazia Middle East, GQ Middle East, gal-dem and more. Hafsa’s debut non-fiction book Modesty: A Fashion Paradox, was launched at the 2020 Emirates Airline Festival of Literature

Follow her on Twitter: @HafsaLodi