A poster during a protest in Rio de Janeiro, on June 13, 2024, reads in English: ‘Forced pregnancy is torture! Neither arrested, nor dead.’ Photo by Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil, used under license

Thousands of Brazilian women took to the streets in different cities this mid-June to protest a proposed bill that could make access to safe and legal abortion even harder, criminalizing rape victims and taking back rights that are already guaranteed to them on the current legislation.

The bill 1904/24 was proposed by an evangelical congressman, Sóstenes Cavalcante, of the same Liberal Party (PL) as former president Jair Bolsonaro, and it was signed by 56 other parliamentarians from the Lower Chamber of the National Congress.

On June 12, the Chamber approved a request to see the bill voted urgently, which allows voting without the bill passing through discussions on commissions. A poll on the Chamber's own site that ran until May 17 shows 12 percent of voters were in agreement with the proposal and 88 percent in disagreement.

If the bill is approved, an abortion after 22 weeks would have the same penalty as a homicide in Brazil, even for women who were victims of sexual violence. This means they could even get a longer sentence than their rapists.

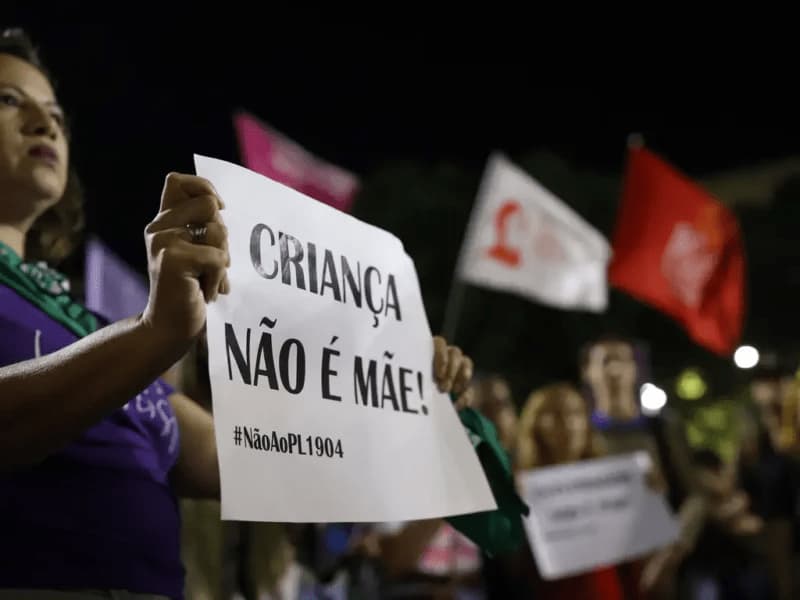

Another sign in Rio's protest against the proposed bill: ‘A child is not a mother! No to the bill project 1904.’ Photo by Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil, used under license

Currently, Brazil allows abortion only in three situations: in cases of anencephaly, if the pregnancy represents a risk to the woman's life or if it is a result of rape.

As reported by Agência Brasil, in 2023, Brazil registered 74,930 rape cases. Among those, 56,820 were against vulnerable people: under the law, when the victim is under 14 years old or has a mental health issue. In total, the country registered 2.687 cases of legal abortion last year, 140 with girls under 14 and 291 with ages between 15 and 19.

To understand what is at stake now, Global Voices talked to Debora Diniz, an anthropologist, researcher and expert in the legal abortion debate, who had to leave Brazil six years ago due to threats related to her stance on the issue. Diniz is associated with the University of Brasilia (UnB) and the NGO Instituto Anis, the latter also signed an action presented at the Supreme Court in 2017 to decriminalize all abortions up until 12 weeks of pregnancy.

To Diniz, the new bill proposal is a move from the Brazilian far-right to push against the Supreme Court itself, putting pressure on their ruling regarding abortion, and President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and his pledges to evangelicals. In 2022, during the election when Lula was up against incumbent Bolsonaro, quotes that would suggest a pro-abortion stance of his were spread out as a means to instill fear and reduce the number of votes, especially among religious voters.

Back then, Lula reinforced a position he has been taking for years: declaring himself, as an individual, against abortion, but defending it as a matter of public health. This time, the president called the latest proposal “an insanity.”

A few days later, in an interview, he commented on the social inequality that presents higher risks to poor women who need to interrupt a pregnancy and questioned Congressman Cavalcante: ”I want to know if his daughter was ever raped, how he would behave. This is not a simple matter”.

Women marching in Avenida Paulista, São Paulo: ‘Reproductive justice save lives’ Photo: Paulo Pinto/Agencia Brasil, used under license.

Global Voices: How do you evaluate what is proposed in Bill Project 1904/24?

Debora Diniz: O que está proposto é um retrocesso de quase 100 anos. É uma tentativa de criar ainda mais barreiras ao acesso ao serviço de aborto legal, em particular, para as meninas vítimas de estupro, mulheres em risco de vida. Acho que os proponentes não esperavam tamanha reação da sociedade brasileira. Na verdade, quando digo que a questão do aborto é que está sendo proposta, ela é o que está na superfície. Na profundidade, está uma queda de braço com a Suprema Corte, está um cheque de lealdade do presidente Lula a suas promessas com a bancada evangélica e o poder médico se movimentando. Mas, em termos de consequências concretas, é a criação de barreiras para as mulheres e as meninas, em particular as mais vulneráveis.

Debora Diniz: What is proposed is a 100-year setback. It's an attempt to create more barriers to access legal abortion services, in particular, to girls who were victims of rape and women with a life risk. I think the proponents did not expect such reaction from Brazilian society.When I say there is an abortion issue being proposed, it is actually what we see on the surface. Deep down, there is an arm wrestle with the Supreme Court, there is a loyalty check to President Lula and his promises to the evangelical bench at the Congress and the medical power moving. But, regarding concrete consequences, it's the creation of barriers to women and girls, particularly the most vulnerable ones.

GV: What would be the immediate effects of legislation such as this?

DD: Seriam o que estamos vendo. Neste caso, teria um aumento da gravidez infantil, por estupro presumido, para quem tem menos de 14 anos. Mulheres em risco de vida sendo obrigadas a morrer, porque a proibição é por tempo gestacional, e o risco de vida é em estágios avançados da gravidez.

DD: It would be what we are already seeing. In this case, we would have an increase in child pregnancies for presumed rape, which is for those under 14 years-old. Women at risk of life being forced to die, because there is a prohibition according to the pregnancy time period, and the risk to their lives increase in more advanced stages of pregnancy.

GV: A study by the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) points out that, in practice, 3.6 percent of cities have legal abortion services and around 10 percent of the women who are raped in the country resort to the procedure. This means we have legislation that ensures it is a right, but in practice, we see a different scenario. What is the reality of women who need this service in the country?

DD: Ou seja, você tem uma legislação que garante, mas tem o outro cenário que é o acesso. Havia uma concentração de acesso no estado de São Paulo, o estado de São Paulo desmantelou esses serviços. E a realidade das mulheres que têm que recorrer aos serviços no país é uma realidade de desterro. Elas têm que atravessar fronteiras, buscar recursos financeiros, enfrentar, além de sobreviver a uma brutal violência, porque para as mulheres em risco de vida, atravessar fronteira é algo praticamente impossível. Mas hoje, além de estar sobrevivendo a uma violência, ela vai ter que buscar recursos financeiros, se ausentar do trabalho, buscar soluções para o cuidado dos filhos. São barreiras que tornam intransponíveis o acesso ao aborto legal.

DD: So, you have a legislation guaranteeing it, but there is another stage, which is access to it. There was a concentration of access to this procedure in the state of São Paulo, then the state of São Paulo dismantled these services. And the reality of the women who need to resort to these services in Brazil is a reality of banishment. They have to cross borders, seek for financial resources, face it, beyond surviving a brutal violence. To women with life risk, crossing a border is almost impossible. But, beyond surviving a violent situation, they will also have to look for financial resources, how to be absent of their jobs, solutions to care for their kids. These are barriers that turn access to legal abortion into something insurmountable.

GV: Historically, how did the debate around abortion issues take place in Brazil? Was it always interrupted, or were there advances?

DD: Esse PL é uma resposta a um momento único na sociedade brasileira que é ação no Supremo Tribunal Federal que pede a descriminalização do aborto nas primeiras 12 semanas. É uma resposta ao que é a onda verde na América Latina, com a descriminalização na Argentina, na Colômbia, no México, no Uruguai. Ou seja, essa fúria da resposta é também uma fúria de uma intimidação de um momento único de transformação da sociedade brasileira. Mas, ao mesmo tempo, a política representativa, da qual não corresponde, não representa, o vivido pelas mulheres, pelas meninas que podem gestar, é uma política feita pelo patriarcado mais tradicional de homens, que vão fazer do aborto um nicho da política extremista, um nicho da extrema-direita, que achou que teria um termômetro de força com o fanatismo. E não teve.

DD: This proposed bill is a response to a unique moment in Brazilian society, which is the action at the Supreme Court asking for the decriminalization of the abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. It's a response to the green wave in Latin America, with the decriminalization in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay. So, this enraged response is also a rage of intimidation for a unique moment of transformation in Brazilian society. But, at the same time, the representative politics, which do not correspond, nor represents what is experienced by women, by girls who can gestate, is a politics made by the most traditional patriarchy of men, who will turn abortion into a niche for extremist politics, a niche for the far right, who thought they could have a thermometer of their strength along with fanaticism. And they didn't.

GV: What explains the difference to other countries in Latin America? Does religion play a part in it?

DD: Eu diria, primeiro, que Colômbia e México estavam com uma Suprema Corte forte para tomar decisões relacionadas a direitos individuais e fundamentais. Na Argentina, quando se decide a nova lei do aborto, foi em um momento de uma mudança de configuração do Parlamento, com novas representações, especialmente com juventude diversa. Essa é uma diferença, porque no Brasil, como nos Estados Unidos e na Hungria, a questão do aborto se configura como um nicho da extrema-direita e como um nicho extremista. E, particularmente pela política representativa brasileira que tem uma sobreposição com as religiões, de uma maneira instrumental das religiões, o que é muito singular da sociedade brasileira.

DD: I'd say, first, that Colombia and Mexico had a strong Supreme Court to rule regarding individual and fundamental rights. In Argentina, when they decided over the new abortion legislation, it was a time of changing for the configuration of their parliament, especially with a diverse youth. This is different, because in Brazil, just as it is in the United States and Hungary, the abortion issue is a niche for the far-right and for extremists. And, particularly because of the Brazilian representative politics, which has an overlay with religions, of an instrumental way for religions, which is very singular to Brazilian society.

GV: President Lula's declaration over abortion, posing him as being in favor of decriminalizing it, was exploited by adversaries in the 2022 elections. He even affirmed he was personally against it and threw the debate to the legislature. How do you read this discussion into the political environment?

DD: Este PL não é sobre aborto. Ele é um teste de lealdade para o presidente Lula, um desafio, uma queda de braço com ele, como é uma queda de braço com a Suprema Corte, com a liminar concedida pelo ministro Alexandre de Moraes, na ação que nós apresentamos, em que derrubou a ação do Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM), que impunha restrições [para interromper gravidezes resultantes de estupro e com mais de 22 semanas de gestação]. É importante explicar que esse PL vem de um extravasamento de poderes, de um abuso de poder do CFM sobre o aborto.

DD: This bill proposal is not about abortion. It's a loyalty test to president Lula, a challenge, an arm wrestling contest with him and the Supreme Court, after the ruling granted by Justice Alexandre de Moraes, in the case we presented, leading to knock down a resolution by the Federal Medical Council (CFM), which imposed restrictions [to interrupt rape-resulted pregnancies over 22 weeks]. It's important to explain that this proposal comes from an overflow of power, an abuse of power by the Council over abortion.

__GV: Can you tell a bit more about your personal experience as someone who have been part of this discussion in Brazil for a while, with a personal cost?

__

DD: Eu trabalho na questão do aborto como pesquisadora, coordeno a Clínica Jurídica, na Universidade de Brasília (UnB), que apresentou com o PSOL (Partido Socialismo e Liberdade) a ação que pede a descriminalização do aborto, quanto a atual ação, que ganhou a liminar e derrubou a ação do CFM. A minha atuação é de pesquisa, de incidência política, em particular com litígio estratégico. Desde a propositura da ação, que pede a descriminalização, eu saí do país por questões de ameaça, por questões de fundamentalismo e extremismo.

DD: I work with the abortion debate as a researcher, I coordinate the Legal Clinic at the University of Brasilia, which presented, alongside PSOL (Socialism and Freedom Party) the case that asks for the decriminalization of abortion, and the current action, which led to the temporary ruling taking down CFM's action. My role is one of research, of political incidence, particularly with strategic litigation. Since the action was proposed, asking for the decriminalization, I left the country due to threats, because of fundamentalism and extremism.

GV: What are the possible ways in Brazil today to rationally discuss issues such as this?

DD: A Suprema Corte decidir a ação. Seja para ganharmos ou perdemos, a gente recomeça esse debate público.

DD: The Supreme Court ruling over the action. Whether we win or loose, we can start this public debate again.

Written by Fernanda Canofre

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.