By Fernanda Wenzel

In August 2019, the number of fires in the Brazilian Amazon skyrocketed, making international headlines and prompting protests in cities like London, Paris and Toronto. While the global community was shocked by images of burning trees and animals, in Brazil, the arrival of the smoke in the country’s business capital and largest city, São Paulo, made the urban population suddenly wake up to the problem.

The crisis also drew the attention of the scientific community, which has since invested more effort into creating tools and data to understand the dynamics of fire in the Amazon, a biome not naturally adapted to burning. “All this caused a stir among researchers, who began to ask themselves, ‘What is going on?'” Manoela Machado, a researcher with the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford, told Mongabay.

Fire doesn’t occur naturally in the Amazon, unlike in the Cerrado, the vast Brazilian savanna, or the forests of California. In the rainforest, it takes human action to start and spread fires, and as such, burning is usually associated with the final step in the deforestation process: once chainsaws and tractors have done their work of felling trees and clearing vegetation, deforesters set fires to burn all the remaining trunks, roots and vines. Ranchers also use fire to renew cattle pastures, especially in areas with low-quality grass and no access to modern farming techniques.

Using fire to clear land is legal in Brazil, but farmers and ranchers must have authorization from state environmental regulators to use the technique. Usually, however, these fires are set illegally and grow out of control.

“Fires, both for grazing and to complete the deforestation process, are the most common ones and cover the largest areas in the Amazon,” said Ane Alencar, director of science at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM).

Indigenous firefighters act to contain the blaze in Roraima state. From January to March, Amazon wildfires had a 254% increase from the same period last year, according to MapBiomas. Image courtesy of the Indigenous brigade group / Roraima Indigenous Council.

On Aug. 10, 2019, several fires were detected across the Amazonian state of Pará. Soon, the Brazilian press revealed they were part of the so-called Day of Fire, an action coordinated by a group of rural producers. The revelation made the links between fire and illegal deforestation even clearer, increasing the pressure on the federal government to take action.

Days later, on Aug. 28, then-president Jair Bolsonaro issued a decree banning legal burning in Brazil’s Amazonian states for the next 60 days. Before then, such bans had only been issued on a one-off basis by state governments.

“Suddenly, there was a moratorium from the top down, with very strong international pressure on the Amazon and also strong internal pressure, because São Paulo went dark [from the smoke],” Alencar told Mongabay. “That’s when I think there was this moment [for the deforesters] to stop and say, ‘Let’s put the brakes on.'”

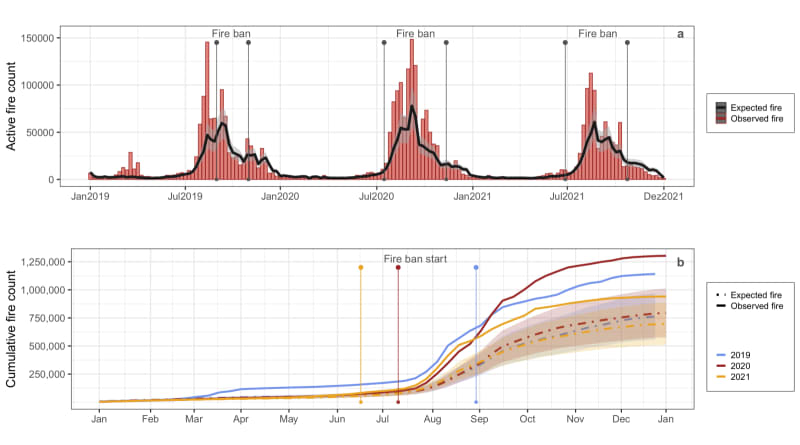

Alongside Machado, Alencar is one of seven scientists behind a newly published study analyzing the effectiveness of the Bolsonaro government’s three bans from 2019 to 2021. They concluded that the first decree succeeded in reducing the number of fires to the level expected under those same climate conditions, but that similar bans issued in July 2020 and June 2021 weren’t as effective.

The scientists list several explanations for this, including the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, which limited enforcement actions in the Amazon and drew media attention away from the issue.

The conclusion didn’t surprise Machado, who said a ban is far too simple an answer to a very complex problem. “It proves that the complexities of the type of fire in the Amazon need to be taken into account when designing a strategy. It’s no use having just one rule,” said Machado, who also works with the U.S.-based Woodwell Climate Research Center.

Firefighting teams use a helicopter to contain the flames near Manaus, the capital of Amazonas state, during the 2023 fires. Image courtesy of Alex Pazuello/Secom/Agência Amazonas.

Concern over the new dry season

After Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office as president in January 2023, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon dropped by 50%. However, fires broke new records last year amid the historic drought that hit the region. “If we hadn’t reduced deforestation, we would have had an even bigger catastrophe. It was a very dry year,” Alencar said.

Another possible reason for the mismatch between the number of fires and the deforested area in 2023 is that much of the swaths of land cleared under Bolsonaro’s watch had not yet been burned by the end of his tenure. “Years of deforestation have accumulated, and it doesn’t take just one year of burning to release all that biomass,” Machado said.

Fire is used even before deforestation and continues to be used for many years after the forest has been felled. It can take up to five years of repeated fires to make a deforested area ready for pastures or soy crops, the experts say. “They burn before deforesting, to weaken the vegetation, and then continue burning for another three or four years to reach a level where they can have pasture,” Machado said.

Fire continued to sweep through the Amazon in the first months of 2024. From January to March, wildfires burned more than 26,369 square kilometers (10,181 square miles) of the Brazilian Amazon, a 254% increase from the same period last year, according to MapBiomas, a research collective that tracks land-use changes through satellite imagery.

Researchers combined their experience on the ground with datasets about fires and weather conditions to effectiveness of fire bans issued by the Bolsonaro administration. Image courtesy of Illuminati.

The forecasts for the coming months look bleak as the dry season intensifies. To make things worse, the region is still under the effects of El Niño, an abnormal warming of the surface of surface waters in the tropical Pacific, which reduces rainfall in northern Brazil, where the Amazon lies.

“The rivers were unable to recover their flow with this year’s rainy season, which was drier than normal. So we’re already starting the dry season with a water deficit, which is very worrying,” Alencar said.

El Niño and climate change are also affecting the Pantanal wetland farther south, a biome that lost 29% of its flooded areas between 1988 and 2018, according to MapBiomas. This year, the fire season has started much earlier than usual: according to Brazil’s space agency, Inpe, 3,372 fires were registered from January to June 25, a 2,000% bump from last year’s 150 fires. If nothing changes, this fire season may be even more devastating than the one of 2020, when the world’s largest wetlands saw 30% of its total area burned, and nearly 17 million vertebrate animals died in the flames.

The situation may be aggravated by an ongoing strike by government environmental agents, who have restricted their activities to internal services since January in protest for better salaries and work conditions. The strike not only undermines the fight against fires but has already affected the preventive work of building firebreaks and raising awareness among rural producers to avoid the use of fire in the coming months.

According to Sonaira Silva, who heads the Geoprocessing Laboratory Applied to the Environment (LabGAMA) at the Federal University of Acre, fire training is crucial to avoid another traumatic dry season.

Scientists concluded only the first of the three burning bans issued by Bolsonaro was effective in reducing the number of fires in the Amazon. Image courtesy of Machado et al. (2024).

“We’ve been warning the region since February, trying to prepare for it,” Silva, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Mongabay from the city of Cruzeiro do Sul in Acre. “Because just issuing a decree and saying ‘I’m going to ban burning’ is ineffective. We need to run campaigns to ask people to burn only when it’s close to the rains, to try to provide some alternative for farmers who we know do recurrent burning. So there are ways to prepare, but we need to run fast.”

Acre is one of the states most affected by fires in recent years. In 2023, the Acre government declared a state of emergency due to the health crisis brought on by the poor air quality. Now, its population is already suffering with the start of a new fire season.

“We go for a walk at night, and it’s already that gray, that horrible smell. When the smoke is at its height, you wake up with a bad feeling because everything is gray, you can’t see the horizon, and when the day starts to heat up, the smoke makes it feel even hotter,” said Silva, who also complained of a burning sensation in her eyes and nose.

According to Alencar, the Amazon is becoming increasingly flammable, a combination of the spread of deforestation, which fragments the forest into small green islands that are more vulnerable to fire, and climate change, which makes the region drier.

“The Amazon is more flammable today because of forest fragmentation and climate conditions, and what will determine whether we have more or less fire is the amount of ignition sources we have,” she said. “So reducing deforestation is super important, and better management of pastures, without fire, is also very important. The Amazon may be flammable, but it will only burn if someone lights a match.”

Banner image: The 2024 fire season has started much earlier than usual: according to Brazil’s space agency, Inpe, 3,372 fires were registered from January to June 25, a 2,000% bump from last year’s 150 fires. Image courtesy of Bruno Rezende/Mato Grosso do Sul state news agency.

Citation:

Machado, M. S., Berenguer, E., Brando, P. M., Alencar, A., Oliveras Menor, I., Barlow, J., & Malhi, Y. (2024). Emergency policies are not enough to resolve Amazonia’s fire crises. Communications Earth & Environment, 5(1). doi:10.1038/s43247-024-01344-4

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay