By Juliet Akoth Ojwang

As millions of farmers suffer each year from crop and livestock deaths due to pests and diseases, some growers in Africa are turning to a host of advanced technologies, artificial intelligence (AI) and online tools to complement the services offered by extension agents in helping farmers combat these losses.

PlantVillage (PV), a U.S.-based nonprofit that aims to improve the lives of farmers and agricultural productivity globally through knowledge and technology, is one key example.

The organization’s eponymous AI PlantVillage app uses a technology called TensorFlow to identify objects on plant leaves and patterns indicating disease outbreaks. The tool, which is developed by using images of both healthy and diseased crop leaves, can therefore help with detecting diseases and pest symptoms for crops such as maize, cassava, Irish potatoes, finger millet and many others.

“We integrated AI into our programs because relying solely on extension officers in the field for surveillance often isn’t sufficient,” Lawrence Ombwayo, the associate director of PlantVillage Kenya, told Mongabay in an interview. He explained that the app was developed to enhance the organization’s extension system, given that agricultural extension services in Kenya and across Africa are under-resourced. The organization found that relying exclusively on its extension officers limited its reach to farmers, hindering PV’s ability to disseminate information about current and emerging crop threats and reducing surveillance of the challenges farmers face, Ombwayo added.

Smallholder women farmers grow maize along with oranges, avocados and a variety of vegetables in Machakos, Kenya. Image by McKay Savage via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

With this app, farmers can leverage their phone’s camera to quickly and effectively address crop health issues. By simply scanning a crop leaf with their phones, the app can instantly identify diseases or problems. This provides farmers with easy access to crucial information on crop health and management, empowering them to make informed decisions that can significantly enhance their yields. Currently, the app has garnered more than 10,000 users who reported an average increase of 40% in crop yields, according to PlantVillage.

Additionally, PV has a mobile SMS system and online WhatsApp groups spread across 22 of the 47 counties in Kenya where the group works. In this way, farmers get to interact in real time with plant doctors, researchers and extension officers. “Currently, we have three WhatsApp groups here in Machakos [county] with an average membership of 95 farmers per group,” said Cynthia Mukhwana, the head of PV’s entomology department.

The PV farmers in Kenya aren’t alone in using such digital tools. A new study shows that researchers have found evidence for potential benefits in using online chat groups among farmers and plant doctors to address common issues that farmers face.

Theresearch, published in March in the journal CABI One Health, analyzes the opportunities and obstacles of using online chat groups for plant health systems similar to the chat groups that are commonly used in human health care. For example, group chats have made it possible for patients to immediately get a hold of health care providers. In case of any problems, being able to talk to a specialist or other community members can be very helpful to patients.

Cynthia Mukhwana, an IPM specialist at PlantVillage, inspects a farmer’s maize farm. Image by Juliet Ojwang.

Some farmers and plant doctors are following suit, using online chat groups to strengthen communication.

“We have a program named PlantwisePlus where we set up plant clinics in many countries around the world to provide advisory services to farmers,” explained Dannie Romney, a Kenya-based co-author of the study and senior global director for development communication and extension at CABI, an international NGO that uses science to solve problems in agriculture and the environment.

These sorts of plant clinics are “a novel way of supporting plant health management,” hinging on “trained plant doctors diagnosing and providing evidence-based management options for crop pests and diseases from samples of afflicted crops, brought by farmers to plant clinics,” the study’s authors write. Digital applications are being used to increase the reach of these programs.

“We’ve worked very closely with government extension offices in countries and supported them to run plant clinics, which were modeled on a human health care system, where you had clinics based in marketplaces, and where farmers, if they had a problem, were able to come and consult a specialist,” Romney said.

Initially, she said, CABI used a paper-based system for its outreach. But over time, the organization introduced digital tools to support data collection, provided tablets and began using Telegram, an app similar to WhatsApp, to facilitate communication with farmers.

However, the effectiveness of chat groups used among farming communities had not been extensively studied, so the researchers set out to do so through a literature review, observations of online chat groups and surveys with participants in Kenya as well as Ghana, Uganda and Sri Lanka.

A fall armyworm damages a corn stalk. Image by Wee Hong via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Previous research documents an array of benefits among online human health care chat groups, including “facilitating efficient communication between health professionals, and linking different departments within hospitals, hospitals with other hospitals, and rural specialists with urban specialists,” the study’s authors write. “Our findings show that there is evidence of the benefits of [chat groups] to human health which can be replicated in plant health,” Romney said in apress release.

Telegram chat groups “significantly increased our efficiency, particularly with the plant clinics,” Romney told Mongabay. “These clinics not only reached people directly at the sites but also leveraged the chat groups to create a network of colleagues and experts. This network allowed for consultation and improved services, extending our reach and impact.”

In 2021, CABI published a chapter in the book titled The Politics of Knowledge in Inclusive Development & Innovation, which revealed that, “On their own initiative plant doctors began to use these chat groups to communicate on a wide range of topics, sharing observations on pest incidence, seeking advice on treating less-common plant pests, discussing logistics, and also socialising with colleagues.” These online spaces “became nationwide peer-to-peer support groups of geographically dispersed plant doctors, with additional input provided by national experts in plant protection and research.”

In Romney’s words, online Telegram chat groups serve as “an early warning system,” with farmers discussing their problems in the field. Through these chat groups, participants have shared photos of their affected plants while plant doctors have identified the issues and made treatment recommendations for plant diseases. This has led to an increase in yields by farmers who were part of the program.

“In 2018-19, when we were working on this paper, we conducted an impact evaluation of the clinics in Kenya and their effectiveness,” Romney said. “Interestingly, during the study period, there was a fall armyworm [FAW] outbreak. What we discovered was that in areas where there were clinics and extension officers trained as plant doctors, farmers experienced a 13% increase in yields and incomes compared to areas without such services. This highlights the significant positive impact of the plant clinics on agricultural productivity and farmer livelihoods,” she revealed.

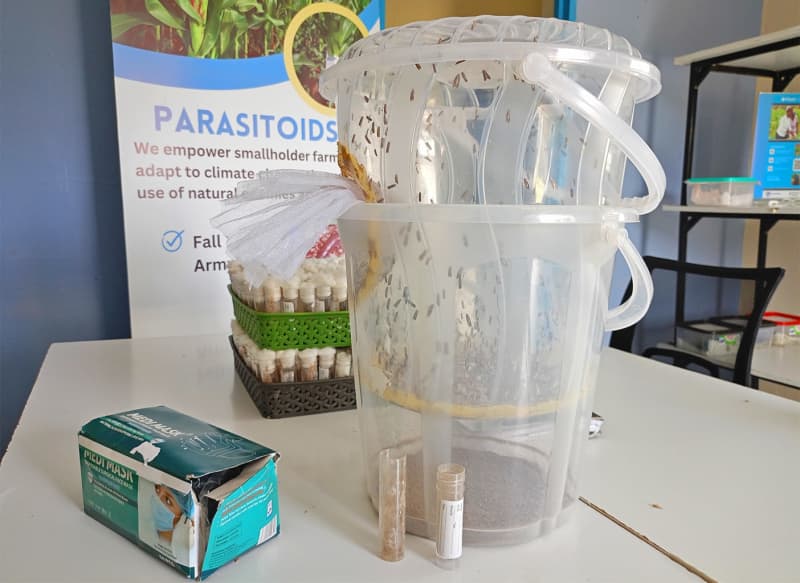

Adult rice moths trapped inside a bucket. They are reared for their eggs, which are later parasitized to produce parisitoids. Image by Juliet Ojwang.

“People often associate WhatsApp and Telegram solely with casual conversations,” Romney said. “However, our research highlighted how these platforms can efficiently bring together groups of people to enhance their work” and to address serious issues.

This is true for PlantVillage, which also uses its chat groups to educate farmers about its work on integrated pest management. IPM, as it is known, aims to minimize pest damage in the most cost-effective way while posing the least risk to people, property and the environment. Through chat groups, PlantVillage informs farmers of its IPM programs, providing up-to-date information about pest life cycles and their interactions with the environment. PV also uses online platforms to communicate with farmers who use the organization’s products, such as biochar fertilizer. (However, since not all farmers have access to smartphones, the group still conducts in-person workshops too.)

PV has three main laboratories and two satellite laboratories for IPM research programs. One of these is in Tala, Machakos county, located in the lower eastern region of Kenya and about 56 kilometers (35 miles) east of the Kenyan capital, Nairobi. Here, the entomology department focuses on the mass production of parasitoids to biologically combat FAW, a significant threat to farmers who predominantly cultivate maize (Zea mays), Kenya’s staple food. A parasitoid is an organism that lives in close association with its host, ultimately causing the host’s death. PV identified two natural enemies of FAW: Trichogramma chilonis and Telenomus remus.

Samples of these naturally existing parasitoids were collected and brought to the PV lab for large-scale reproduction. To facilitate this process, the department chose two suitable hosts: FAW and the rice moth, which researchers rear for their eggs, which then undergo parasitization to produce more parasitoids.

The eggs are evenly spread on ivory cards using odorless glue. Once prepared, these cards are then exposed to the parasitoids. “For parasitization to occur, the parasitoids lay their eggs inside the eggs of fall armyworms. The parasitoid offspring feed on the contents of the fall armyworm eggs, completing their development within 7-10 days, depending on the temperature, before emerging as mature parasitoids,” Mukhwana noted.

To provide farmers with parasitoids for use on their lands, the prepared cards are placed in envelopes and transported to the farms a day before the parasitoids fully emerge. Once released, the parasitoids integrate with the local population, locate the fall armyworm eggs and parasitize them. Each card is sold for 300 shillings (approximately $2.30).

“We initially turned to PlantVillage’s parasitoids during a severe fall armyworm outbreak,” farmer Diana Kimani told Mongabay. “At the time, we relied on synthetic pesticides for our 3-acre maize farm, which proved to be prohibitively expensive.” She elaborated that the pesticide they had used was sold in 100-milliliter (3.4-fluid-ounce) bottles, each costing 700 shillings ($5.42), and required dilution to fill 10 buckets. This solution needed to be sprayed at least six times before harvest, not including labor and additional costs.

Diana Kimani, a PlantVillage agent, speaks with farmer Jemimah Kioko on the status of her maize farm after using biochar fertilizer. Image by Juliet Ojwang.

Diana Kimani and her husband, Steve Kimani, shell rosecoco beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) after a small harvest, which was impacted by heavy rains. Image by Juliet Ojwang.

In contrast, using parasitoids required only 12 cards to eliminate the infestation, significantly reducing the need for frequent spraying. This approach resulted in better maize yields compared with the previous season.

In addition to the IPM strategies, PV’s mycology department, which conducts extensive research in the use of beneficial fungi to kill FAW larvae, also offers biochar fertilizer for sale, which goes for 1,800 shillings ($13.95) per 50-kilogram (110-pound) sack. “We wanted to provide farmers with an alternative to synthetic options, so it’s a comprehensive package,” said Mercy Kemboi, the department’s lead.

Farmer Jemimah Kioko, who uses the biochar, talked about the benefits to her 7-acre farm, where she plants coffee, maize and various other crops. “At the beginning of this year, I traveled abroad to visit my daughter and returned late to start planting. PlantVillage provided me with their biochar fertilizer, which I applied to my maize plantation. Now, the crops are thriving,” she said.

All of this work is food for thought in the farmers’ chat group conversations as noted by the aforementioned farmers. They disclosed that the WhatsApp groups they were part of helped them stay updated with new information. And these groups also provided a platform for asking follow-up questions about the PlantVillage products they used on their farms.

One phenomenon that PV experts have observed is that chat group participation is influenced by factors such as planting seasons. For instance, during maize or bean planting seasons (March-May during long rains or October-November during short rains), farmers are very active, asking questions about diseases affecting their crops. But in the offseason (December-February), participation is significantly low.

To cope with this, PV organizes various trainings for the farmers. “During offseasons, many trainings are conducted with the farmers to keep the flow of information sharing, as farmers during this time are preparing their fields for the incoming planting season.”

Sharing video clips of farming or extension education in the groups also helps maintain the conversation, as farmers often ask questions about the clips.

While acknowledging the lack of access to smartphones for some farmers, PV sometimes trains participants to become “lead farmers” who later train their colleagues on what they have learned. Some of these farmers who are really good at sharing information end up being the organization’s agents. There are currently 11 agents in Machakos, with Diana Kimani being one of them. “As an agent, I go around educating farmers about our products, their usage and their benefits,” she said.

Kimani received a smartphone from PlantVillage, which she uses to maintain communication with the farmers she has trained and to track the sales of her assigned products. Each agent, including Kimani, is responsible for selling a specific number of products, such as 10 bags of biochar fertilizer, within a set time frame. However, she still conducts some training sessions in person because not all farmers have access to phones or smartphones. This lack of access remains a significant obstacle to fully utilizing digital tools and chat groups for improving plant health.

Banner image: Farmer Florence Ochieng harvests green maize in Trans-Nzoia, Kenya. This image is for representational purposes only. Image by CIMMYT/ Peter Lowe via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Citation:

Jomantas, S., Wood, A., Munthali, N., Ochilo, W., Thakur, M., Romney, D., & Kadzamira, M. (2024). Looking at human healthcare to improve agricultural service delivery: The case of online chatgroups. CABI One Health. doi:10.1079/cabionehealth.2024.0008

This article was originally published on Mongabay