In Switzerland, a bold initiative is underway: freezing human feces to preserve global biodiversity.

However, this isn't just about safeguarding nature's diversity of plants and animals — human gut biodiversity is also at stake.

"We have discovered that we are losing biodiversity in the gut," medical microbiologist Adrian Egli from the University of Zurich tells dpa. "There is much more diversity in Amazon populations compared to those in the West. This has to do with stress, antibiotics and diet."

Saving the stool

"There are a thousand billion bacteria in one gram of stool, 125 times as many as there are people on the planet," Egli says. "It's unbelievable when you think about what lives inside you." There are between 300 and 500 different species in one person.

Now, an international effort aims to conserve this biological treasure through a so-called Microbiota Vault, akin to a huge rescue workers' vault for human faeces.

Researchers can hold several varieties of food plants in a container similar to the seed vault on Spitzbergen. Bacteria can survive for decades in a special solution, Egli says.

Research into intestinal flora is currently still in its infancy. "It may be possible to use knowledge about the microbiome to develop therapies to positively influence obesity, diabetes, rheumatic diseases or chronic intestinal inflammation," he says.

The microbiome also includes fungi and viruses, but bacteria are particularly important because they have many significant metabolic properties.

Bacteria in glass plates

At the University of Zurich, Adrian Egli's laboratory buzzes with activity. People in white coats are working with all kinds of sterile tools and equipment.

Laboratory manager Diana Albertos Torres is inspecting Petri dishes that contain bacteria that has been extracted from stool samples.

To the untrained eye, only small dots can be recognized on the red agar plate. Torres knows that it is probably Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium that causes pneumonia, among other things. However, there is no danger.

"No, bacteria don't jump out of the dish," Torres reassures with a laugh. Work in the laboratory is carried out under the necessary safety precautions.

Microbiome influences diseases

Thanks to new machines and methods, it is now possible and affordable to conduct genetic research into gut bacteria. "There are new discoveries every week," says Egli.

"And the whole of humanity can benefit from analysing bacteria." The microbiome is linked to diseases such as cancer and autoimmune disorders, for example.

One special feature: the digestive tract is home to vast numbers of bacteria that do not tolerate air, so-called anaerobic bacteria.

As Egli explains, little research has been done on them. "There are probably 1,000 times as many bacteria in the gut that don't tolerate air as those that we have been able to isolate and know about."

Helpful in the fight against cancer?

It is conceivable that the targeted use of bacteria could one day improve the response to cancer therapies, says Egli. Stool transplants are another field of medicine. "A stool sample with an optimal microbiome given to a patient - studies have shown that this can contribute to recovery."

Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello, a microbiologist from Venezuela who conducts research in the United States, has been campaigning for an intestinal bacteria vault for years.

She was one of the first to establish the extent to which bacterial diversity in humans differs depending on where they live and their living conditions, using samples from the Amazon region as an example.

Self-experiment in Africa

A few years ago, British epidemiologist Tim Spector conducted an experiment: he spent three days with indigenous hunter-gatherers in Tanzania and shared their lifestyle and food, including fruit pods from the baobab tree and all kinds of meat.

After just three days, the biodiversity in his gut had increased by 20%. as he reported in the online journal "The Conversation."

Why is diversity important?

A team led by microbiologist Frances Spragge from the University of Oxford has just reported in the journal "Science" that gut bacteria can, for example, prevent the colonization of pathogens that make people ill.

People can contribute to a good microbiome themselves. For example, a diet rich in fibre is important. This refers to largely indigestible, plant-based food components.

They have an influence on satiety, how long food remains in the stomach and intestines and how well nutrients are absorbed by the body.

Important: lots of fibre

According to the German Nutrition Society (DGE), a high fibre intake has a protective effect on cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure and colon and breast cancer. High-fibre foods include edible plant seeds, nuts, wholegrain products as well as vegetables and fruit such as artichokes, peppers and rhubarb.

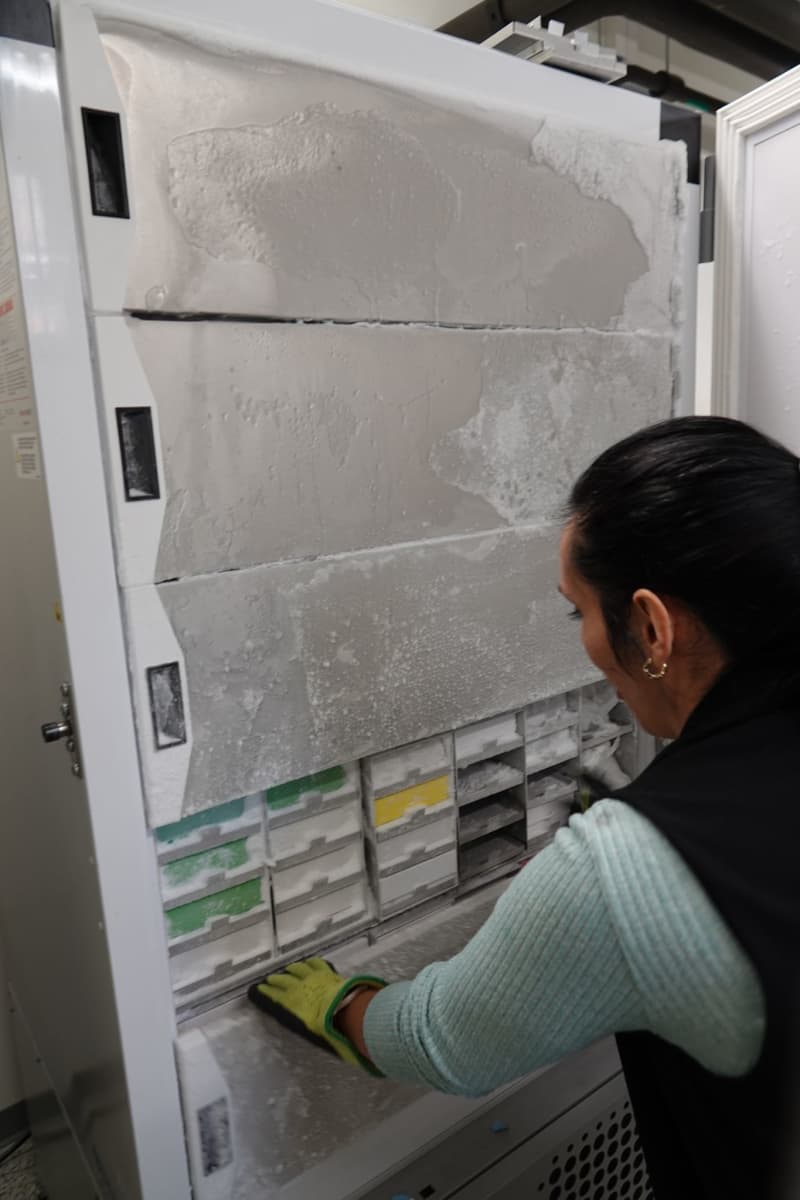

Egli works with Pascale Vonaesch from the University of Lausanne and Nicholas Bokulich from the University of ETH in Zürich in the "Microbiota Vault" pilot team. Egli has the freezers in which around 2,500 stool samples from Ethiopia, Laos, Puerto Rico and Switzerland and other countries have been frozen at minus 80 degrees Celsius.

It's not easy: samples have to be frozen within hours in order to preserve bacterial diversity. Dominquez-Bello has shock-frozen samples in remote Amazon regions using liquid nitrogen. A continuous cold chain and lots of paperwork are required for export to the samples to Switzerland.

According to Egli, the pilot project is almost complete, with largely positive results. Tens of thousands of samples from all over the world will soon be arriving in Zurich.

A vault for final storage will have to be built for this, he says, since the ice cabinets in his laboratory will soon no longer be sufficient.