By Elizabeth Fitt

For the first time in history, we now farm more seafood than we catch from the wild. At the same time, overfishing of wild fish stocks continues to increase even as the number of sustainably fished stocks declines.

That’s according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) latest “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture” (SOFIA) report. The 2024 instalment of the report, a biennial collection of data that outlines the FAO’s vision for the fishing and aquaculture sectors, was released June 8 at a high-level ocean stakeholder event in Costa Rica. It tempers aquaculture progress with a warning that fisheries management is failing to adequately support sustainable wild fish stocks.

The report summarizes the FAO’s “Blue Transformation road map” and encourages countries to implement it. In 2021, the FAO launched the road map, a strategy for meeting the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14), Life Below Water, by 2030, to improve the social, economic and environmental sustainability of aquatic food and feed more people more equitably. Sustainably growing aquaculture and better managing fisheries are central to the Blue Transformation road map, but progress is “either moving much too slowly or has regressed,” the report says.

“The FAO’s ambition for a Blue Transformation is necessary, admirable and ambitious,” Bryce Stewart, a senior research fellow at the U.K.-based Marine Biological Association, told Mongabay. “It appears to have resulted in improved data and a higher profile for blue foods from fisheries and aquaculture as a key way to addressing global issues around inadequate nutrition and inequality.”

Intensive fish farming in Vietnam, 2012. More than three-quarters of the global fisheries and aquaculture workforce is based in Asia. Image by Yvan Bettarel @IRD via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Key takeaways

The SOFIA report has been giving policymakers, scientists and civil society a deep dive into the global fisheries and aquaculture sectors since 1995. The flagship report, released every two years, reviews FAO and broader U.N. statistics, including those the FAO has been collecting on 500 fisheries stocks globally since 1974. It provides data, analysis and projections that inform decision-making internationally.

The 2024 report brings in data that became available since the last SOFIA report was published, in 2022. An estimated 600 million people still rely, at least partially, on small-scale fisheries and aquaculture for their livelihoods, while people relying on direct employment in the sectors increased by 4 million, to almost 62 million, since the 2022 report.

Women make up 24% of fishers and fish farmers, up 3% on SOFIA 2022, and a stable 62% of processing workers. More than three-quarters of the global fisheries and aquaculture workforce is based in Asia, which continues to dominate both wild fisheries and aquaculture, accounting for 70% of global aquatic animal production and more than 90% of aquaculture.

Fisheries and aquaculture production rose by more than 4% to an all-time high of 223 million metric tons, worth a record $472 billion, the report finds. Aquaculture drove growth, pulling ahead of capture fisheries in aquatic animal production to 51% of the global total. Almost 63% of farmed aquatic animals and plants came from inland waters and 37% from marine and coastal areas.

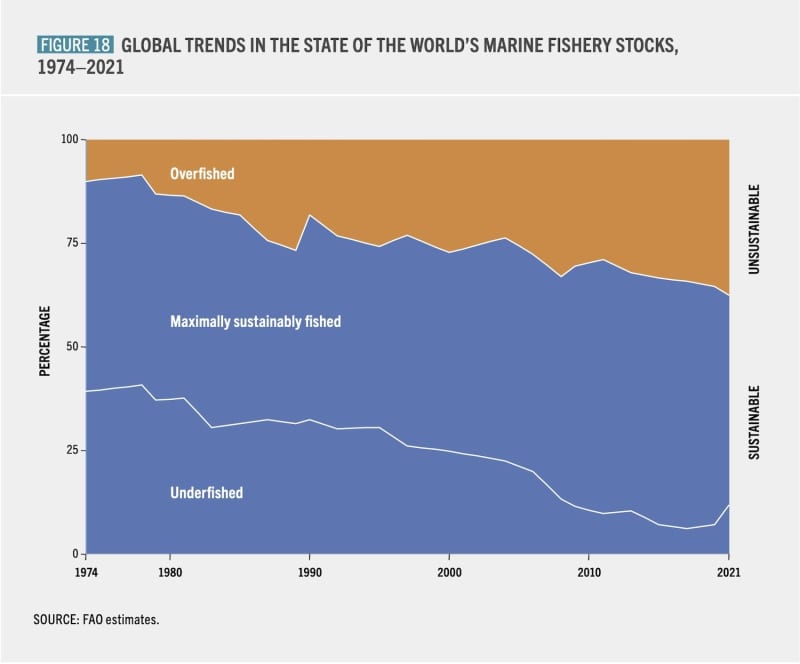

The number of sustainably fished marine fish stocks fell more than 2%, down to 62%, since SOFIA 2022. This continues a striking long-term decline from 90% in the 1970s that is “particularly worrying,” Stewart said.

“Given the definition the Food and Agriculture Organization uses to determine sustainability, this decline is likely an underestimate,” said Ashley Wilson of the Philadelphia-based public policy group The Pew Charitable Trusts’’ international fisheries project.

“Sustainably fished” includes stocks that are “maximally sustainably fished,” which make up half of the global total, and “underfished,” which have rallied from just 7% in the 2022 report to 12%. The remaining 38% of stocks are defined as “overfished,” up from 35% in 2022.

When it comes to the 10 fish species we land the most, however, the picture is a little brighter. Around 79% of these were fished within biologically sustainable levels, higher than the global average, which shows these important stocks are better managed than most and that conservation efforts can be effective, according to the report. “Urgent action is needed to replicate successful policies and reverse declining sustainability trends,” the report says.

“Good progress” has been made in terms of countries agreeing to monitor and report across biological, social and economic sustainability dimensions, and on agreements to combat harmful fishing practices, according to the report. But actual implementation of these measures is “lagging,” it says, and fishery sustainability “continues to drift from its target.”

Too little investment from the public and private sectors, lackluster political will and insufficient international collaboration are what’s preventing better fisheries management, Stewart says. The good news is that “we have the knowledge and expertise to do what it takes,” he said. “We need to highlight, learn from and draw inspiration from those fisheries and aquaculture initiatives that have achieved genuine sustainability and delivered benefits in an equitable way.”

Aquaculture and the ‘Blue Transformation’

The SOFIA report continues FAO’s long-standing promotion of aquaculture as a way to meet SDG 14. Aquaculture production may have hit a record-breaking 130.9 million metric tons, but it still has untapped potential to contribute even more to human nutrition, especially in low-income countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, the report says.

Aquaculture production grew 6.6% since 2020 and is projected to grow a further 17% by 2032, putting it on track to exceed the 22% increase by 2050 that the report says is required just to keep pace with projected human population increases.

“The report highlights a huge potential for aquaculture to bring economic and food security to countries around the world,” Bryton Shang, CEO of San Francisco-based aquaculture tech startup Aquabyte, told Mongabay.

When the 2022 SOFIA report came out, Shang said there was a lot of talk but little action around sustainable aquaculture. Mongabay asked whether that was still the case two years down the line.

“There has absolutely been more action from regulators, nonprofits and businesses,” Shang said, highlighting new fish welfare and environmental protection policies in Iceland and stricter enforcement in Norway and Chile. “Conversations around the industry itself are also evolving,” he added, and new types of partnership are developing. For example, the Walmart Foundation and Chilean salmon farmer Blumar Seafoods have partnered with The Nature Conservancy to experiment with co-farming seaweed as a way to improve fish-farm water quality.

This uptick in crucial innovations and regulations has “accelerated the production of sustainably and ethically grown seafood,” Shang said. And the impacts have pushed Aquabyte’s revenue over $10 million, he said, with the business expanding into Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

Aquaculture isn’t all a bed of anemones, however. Governments and regulatory bodies aren’t forward-thinking enough when it comes to promoting sustainable aquaculture development, Shang said. There’s a tendency to focus on the industry’s historical flaws rather than where it’s headed. “Because the industry’s social license to operate has been challenged, so has its regulatory license, and thus the industry as a whole has not kept up with demand,” he said.

A salmon farm in the Reloncaví estuary, Chile. Image by Jackripper11 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Aquaculture fish being processed in Norway, 2015. Image by Anne-Line Aaslund/Innovation Norway via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Ecological and social damage caused by poorly managed aquaculture is well publicized: Farmed salmon is often fed wild fish caught in West Africa, destabilizing both fish stocks and the region’s food security. Eutrophication and the transfer of toxic chemicals, diseases and parasites to wild fish populations are widespread around fish farms, as summed up in a 2017 reference article published by Elsevier.

Many of the problems are linked to in-demand intensively farmed species such as salmon and shrimp that rely on fish-based diets. Farmed shellfish, on the other hand, can actually improve the surrounding ecosystem, according to research published in Marine Policy. Farming herbivorous fish using indigenous Hawai’ian techniques has also been reported to improve water quality and increase native fish populations.

“Producing food has impacts,” Manuel Barange, director of the FAO’s fisheries and aquaculture division, told Mongabay in an emailed statement. “Aquaculture allows us to control and analyze what impacts we are prepared to accept and which ones we do not.” In May 2024, FAO members agreed to a set of sustainable aquaculture guidelines to help states navigate these trade-offs.

Climate adaptation and aquatic foods

Aquatic foods will play a key role in mitigating the impacts of climate change, the report says, partly because future terrestrial food production will struggle to deliver food security. At the same time, “As the effects of climate change intensify and global demand for blue food continues to increase, it will become even more difficult, but more important, to manage fisheries sustainably,” Stewart said.

“To cope with the changes that will be coming upon us, I have little doubt that we’ll be turning increasingly to the ocean for the solutions to our problems,” Peter Thomson, ambassador of Fiji and special ocean envoy to the U.N., said at the launch of the SOFIA report in Costa Rica.

Adapting both fishing and aquaculture to the instability in marine ecosystems and increasing extreme weather events that climate models predict is “vital,” the report says. It recommends dynamic fishing season adjustments and basing access to fishing grounds on near-real-time monitoring systems, together with disaster preparedness and promoting livelihood diversification.

We need to do better because our actions today “will lessen the immense trials of those who are inheriting the future,” Thomson said. “It is in this context that the FAO’s Blue Transformation strategy assumes such importance for what lies ahead.”

Banner image: Grouper farming in Aceh, Indonesia, in 2012. Photo by Mike Lusmore via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Citations:

Adriane K. Michaelis, William C. Walton, Donald W. Webster, L. Jen Shaffer, Cultural ecosystem services enabled through work with shellfish, Marine Policy, Volume 132. (2021).104689, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104689

Troell, Max & Kautsky, Nils & Beveridge, Malcolm & Henriksson, Patrik & Primavera, Jurgenne & Rönnbäck, Patrik & Folke, Carl & Jonell, Malin. (2017). Aquaculture. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.02007-0

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay