The start of tsuyu, or the rainy season, has already started in Japan. I’ve always wondered how the beginning of the rainy season was determined, for no sooner is the season announced than we experience a week of beautiful, sunny weather.

It’s as if mother nature is snubbing her nose at all the meteorologists and saying, “Think ye can pin me down, d’ye? Well, take that!”

The answer to this question lies in first understanding why it rains.

The baiu zensen

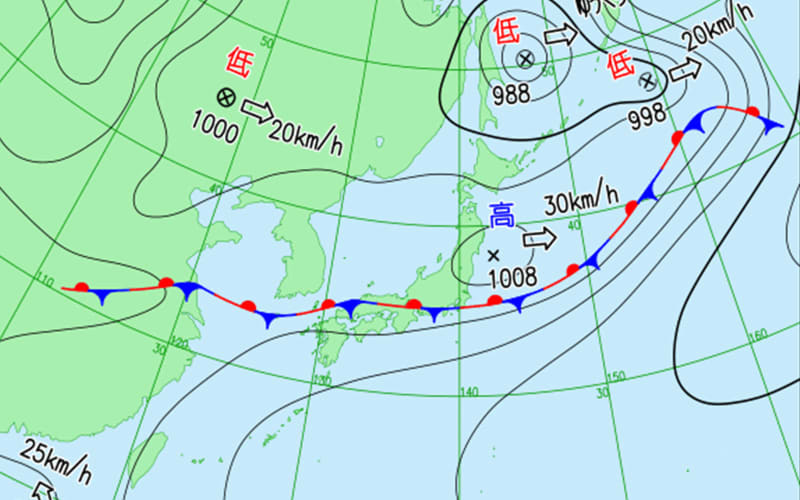

From about May to July, there is a stationary front over Japan known as the baiu zensen (梅雨前線, the seasonal rain front). Check a weather map of Japan at this time of year, and you’ll find a flat front with semi-circles on the northern side and triangles on the southern side.

This indicates a stationary front or a non-moving boundary between two differing air masses. Because of the baiu zensen, long continuous rainy periods can linger in the area affected.

In East Asia, air masses of differing temperatures and humidity from areas of high atmospheric pressure over the Sea of Okhotsk and the Pacific Ocean meet along the baiu zensen, creating clouds and rain. The strength of these two regions bumping up against each other prevents the front from dissipating.

When there have been several days of unsettled weather, and it looks likely to continue to be rainy or cloudy for several successive days, the Japanese Meteorological Agency will announce that a particular region of Japan has entered tsuyu iri (梅雨入り, the rainy season).

Similarly, tsuyu ake (梅雨明け, the end of the rainy season) is announced when the rains have stopped, and there have been consecutive sunny days. If the past is anything to go by, the rainy season will end in the northern part of Kyushu around mid-July, or just in time for the Hakata Gion Yamakasa festival.

Plums and mold

While the mechanics of tsuyu are relatively straightforward, there are many aspects about the season that can be somewhat confusing. The first question many people have concerns the name of the season: tsuyu, quite literally, means “plum rain.”

Why is the season called “plum rain” when Japan’s beloved ume no hana (梅の花, plum blossoms) typically bloom in February? Because (holds one theory) the rainy season coincides with the picking of said plums for making umeshu (梅酒, plum liquor) and umeboshi (梅干し, dried and pickled plums).

Another theory maintains that the original name for the season was baiu (黴雨, lit. “moldy rain”) due to the high humidity and heat creating the perfect conditions for mold to grow.

The “moldy” half of the name, bai (黴), was replaced with the Chinese character ume (梅, plum), which could be read the same way. Lending some credence to this theory is the fact that in China, the rainy season is also written 梅雨 (though pronounced “meiyu”) and is written by some as 霉雨, where 霉 means “mold.”

Interestingly, the kanji for plum (梅) contains the radical 毎 in it, which means “every” as in “every day,” giving the word baiu (梅雨) the sense of it raining every day. In Korea, the name for the season is jangma (장마, lit. “long rain”).

Japan’s old calendar

The second question people have regarding tsuyu is the traditional name of the month in which the rainy season falls: minazuki (水無月, lit. “no water month”). It comes from Japan’s old calendar, called kyuureki (旧暦) or inreki (陰暦), which was based on the lunar cycle. June, or minazuki, was the time of the year that water was more essential to rice fields.

The kyuureki is still used today for traditional events, the marine products industry and fortune-telling. Some modern-day calendars show both dates.

A look at the Western calendar is also instructive. While September is now the ninth month of the year, the name means “seventh month.” In calendars before 1752, September was considered the seventh month, October the eighth month, November was the ninth, and so on.

The old name for June, minazuki, is aligned more closely to the drier month of July of the former calendar.

The summer months of July (Julius Caesar) and August (Augustus Caesar) today were formerly known as Quintilis and Sextilis (the fifth and sixth months of Romulus, respectively) in the 10-month calendar of ancient Rome in which the year started in March.

The Japanese calendar experienced a similar change in the latter half of the 19th century when the tenporeki calendar, a lunisolar system used for just under 30 years from 1842 to 1872, was abandoned in favor of the Gregorian calendar.

To make the change, the second day of the 12th month of the fifth year of Meiji (明治5年12月2日) became the first day of the first month of the sixth year of Meiji (明治6年1月1日)—so December of 1872 lasted only two days!

The month of no water

Because of the shift from a lunisolar calendar to a sun-based one, the former names of the months are sometimes off by several weeks. For example, June 7 is May 13, according to kyuureki.

May (五月, gogatsu) is also known by its former names satsuki (五月 or 皐月, “five-month”) and samidare (五月雨, also read satsuki ame) which mean “May rain.” It is synonymous with the rainy season.

The old name for June, minazuki (again, the month of no water), is aligned more closely to the drier month of July of the former calendar. Some believe the name may also derive from the great need for water for rice planting, which occurs during this time of the year.

If you look at June 11 on a traditional Japanese calendar, which gives both modern and kyuureki dates, you may see 入梅 (nyubai, lit. “enter + plum”). During the Edo period, the rainy season was believed to begin on or around June 11—also known as kasa no hi (傘の日, “Umbrella Day”).

So as we enter the rainy season, I offer a prayer to both Kuraokami, the dragon god of rain, and Raijin, the god of lightning, thunder and storms: May this season bring us all the rain we need and no more—and may it be over sooner rather than later.

Do you enjoy tsuyu? Do you hate tsuyu? Let us know in the comments!