A new study published in the journal Scientific Reports lends support to a body of research suggesting that reading on electronic devices reduces comprehension. The study found that reading on a smartphone promotes overactivity in the prefrontal cortex, less frequent sighing, and lower reading comprehension.

More than ever, people are reading via electronic devices — for example, consuming news, reading books, and studying for exams on smartphones and tablets. But on top of causing eye strain and headaches, research suggests that using these devices leads to poorer reading comprehension — although it is unclear why.

Study authors Motoyasu Honma and team launched a study to explore a possible reason for this effect. The researchers focused on two factors known to be associated with cognitive function and performance — the visual environment and respiration patterns. They proposed that the visual environment of reading on a screen may alter respiratory function and brain function, which may interact to impact cognitive performance.

“A woman working next to me was a constant loud sigher, and I began my research by wondering why she sighed so much,” explained Honma. “As I looked into previous studies, I became interested in the fact that sighing has a negative impression on social communication, while it has a positive effect on cognitive function. Now that I think about it, she may have been subconsciously using sighs to improve her work efficiency.”

A sample of 34 Japanese university students took part in the experimental study. Each student participated in two reading trials, where they either read a text on a smartphone or read a text on paper. The two texts were passages taken from two novels by the same author, and the conditions were counterbalanced so no student read the same text twice.

While the students read, they wore functional near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) headbands that measured activity in the prefrontal cortex and masks around the mouth and nose to measure respiration patterns. After reading, the participants completed a reading comprehension test that included 10 questions related to the content of the passages.

First, the findings revealed that the students performed better on the reading test if they had read the passage on paper versus a smartphone — regardless of which novel they read. This result is consistent with the literature suggesting that reading on electronic devices interferes with comprehension.

Next, the researchers found differences in students’ respiratory activity depending on the reading medium. When reading on paper, the students elicited a greater number of sighs compared to reading on a smartphone. A sigh was defined as a breath that was twice the depth of an average breath during a session.

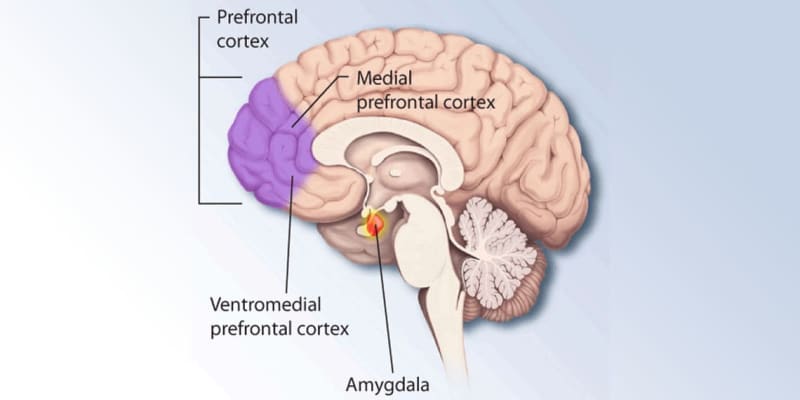

The findings further revealed that the students’ prefrontal brain activity increased during reading, in either condition. But interestingly, this brain activity was higher when reading on a smartphone compared to reading on paper. Moreover, increased activity in the prefrontal cortex was associated with a decrease in sighing and lower reading comprehension.

While interpreting these findings, the researchers note that previous studies have suggested that people increase their sighing when facing demanding tasks that increase cognitive load. The elevated prefrontal activity among students reading on a smartphone may suggest increased cognitive load compared to reading on paper. But reading on a smartphone seemed to inhibit sighing compared to reading on paper.

“There is previous research that shows that even conscious deep breathing has a positive effect on cognitive function, so I propose that those who use electronic devices for long periods of time should include deep breathing in places,” Honma told PsyPost.

The authors suggest that the interaction between increased brain activity and decreased sighing may be responsible for the decline in comprehension. For those who read on paper, the moderate cognitive load led to sighing which may have helped “restore increased respiratory variability and control of prefrontal brain activity.” But for those who read on a smartphone, the more intense cognitive load prevented sighing, leading to elevated brain activity.

“The convenience of smartphones and other electronic devices is immeasurable, and I believe that much of what we do cannot be replaced by paper,” Honma said. “However, if both smartphones and paper can serve the same purpose, I would recommend paper.”

But it is currently unclear how age and familiarity with digital devices might influence the new findings.

“The participants were young people around 20 years old,” Honma noted. “They are the generation called ‘digital natives,’ but even so, I guess that they started using digital devices only around the time they were in middle or high school. In this regard, if someone has grown up exposed to a digital environment from the time of infancy, then the results may be more positive for smartphones, contrary to the results of this study. On the other hand, I am wondering to what extent our brain is a system that can adapt to the digital environment.”

While further research is needed, the findings shed light on a potential harmful effect of smartphones, which have been increasingly used during the pandemic. “If the negative effects of smartphones are true,” Honma and colleagues write in their study, “it may be beneficial to take deep breaths while reading since sighs, whether voluntary or involuntary, regulate disordered breathing.”

The study, “Reading on a smartphone affects sigh generation, brain activity, and comprehension”, was authored by Motoyasu Honma, Yuri Masaoka, Natsuko Iizuka, Sayaka Wada, Sawa Kamimura, Akira Yoshikawa, Rika Moriya, Shotaro Kamijo, and Masahiko Izumizaki.