On a moody Sunday afternoon at 50 Vanderbilt Avenue in New York, at an intimate private reading of his latest book, The Reservoir, David Duchovny was sitting in a green leather armchair, bringing the voice of his book protagonist, Ridley, to life.

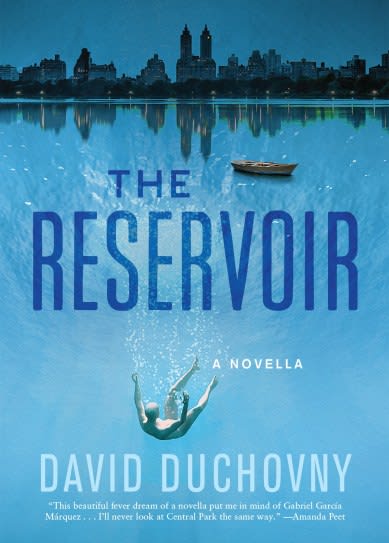

Set in a glamorous dormitory in Manhattan with stunning views of Central Park, Duchovny’s novella, The Reservoir, depicts the man in search of a resolution, stuck behind the walls of his upscale twenty-floors-above-ground “cabin in the sky.”

Ridley is a Wall Street veteran aware that his job was “never quite a fit for his soul.” As a way to make sense of his life, he begins capturing a time-lapse film series of the sunrise over the reservoir he entitled Res: 365.

A former Wall Street veteran, quarantined by the coronavirus, becomes consumed with madness—or the fulfillment of his own mythic fate.

“Res” is a riddle and a guidepost, sort of. It can mean a “thing” or an abbreviation for reservoir and resolution, Duchovny tells the reader. All three, perhaps. There’s a surface of still water, and then there’s a deep end.

“Water is the human symbol of the depths,” explained Duchovny. “It was the New York version of getting underneath the surface of things at a time when we were all kind of ingesting truth through our screens and not through face-to-face communication,” he shared his intention for the way he situated his novel.

The resolution, as the intention or an explanation, may mean different things to different people. Ridley is looking at his time-lapse frame on day 250, seeing for the first time something that was already there. He’s convinced that he sees a flashing light across Fifth Avenue coming from a damsel in distress. From that point on, everything spirals out of control for Ridley. He gets lured out of his isolation by flashing lights, “much like Gatsby,” according to the author.

David Duchovny writes like Bob Dylan, but in prose. There’s irony, poetry, there’s social commentary. There’s a brooding outrage. And there’s romance, too.

White House Correspondent Ksenija Pavlovic McAteer

As David Duchovny stepped away from Ridley for a moment, I asked him what kind of resolution he was looking to achieve through the writing process of *he Reservoir.*

“I’m just trying to share my point of view,” Duchovny responded. “I don’t believe in eternity or the afterlife or anything like that. So I feel like that’s the best thing I can do while I’m here, to—if anybody cares—just say what I’m thinking and seeing. And doing it not in a way of autobiography or a memoir, which I don’t really quite respect as much as writing. So, it’s putting it through the crucible of art, and turning it into something hopefully universal, rather than just what I see and think and feel and hear,” Duchovny revealed.

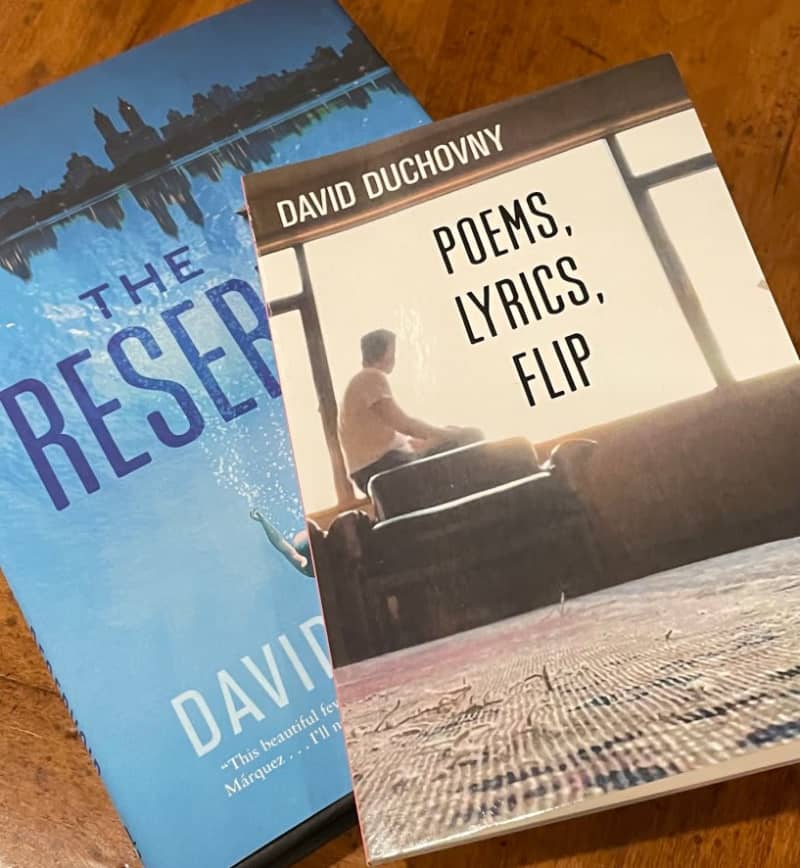

The chapbook POEMS, LYRICS, FLIP comprises select lyrics from David Duchovny three studio albums and his poems. In reverse, the chapbook is a full-color flip book of one of the time-lapse videos David created while writing The Reservoir.## Six shall take the place of sex

Duchovny’s protagonist is a divorcee in search of modern-day salvation. He is staring at the “death in the air,” the virus that engulfed his existence, ordering contactless take-outs and leaving “outrageous tips” through internet dot.com “like a secret benefactor” to the struggling New York local restaurants.

Ridley is looking for a sign, a flickering light, a Morse code, a secret language, an intuition, an escape. An SOS. An antidote to the cruel loneliness of the pandemic.

Three

Oh, make it a game, kids, remember how to play

*Keep Away*

and stay, please baby baby, please stay

the fuck away from me.

The wicked witch has cast her hex:

*Six shall take the place of sex*

Poem by David Duchovny in Poems, Lyrics, Flip

From the beginning of The Reservoir, the reader encounters Duchovny’s off-the-cuff classical literary references. That’s his version of the name-dropping New York is famous for. No, Duchovny is not pretentious. He is just that well-read.

Duchovny, the author, shared at the private reading on 50 Vanderbilt Avenue that he would be “terrified” to read in front of his former Yale professor, the late Harold Bloom, an opinionated and equally controversial American literary figure.

In person, Duchovny is kind and polite, open to having an interesting conversation one can’t have in two-minute soundbites made for TV. The perk of being in the Yale circle.

I asked him about the “pressure to fit in,” his experience, and how others can overcome it.

David Duchovny

“When I first started acting, my initial agents, managers would say, ‘Don’t tell them you went to Princeton and Yale. Because, we don’t want actors to feel like maybe they’re not as smart as you are,'” David recalled his beginnings.

“Then, when I came back to writing, it was like, why is that actor writing? So, you’re always going to be kind of straitjacketed by a first impression or thumbnail sketch of what somebody thinks a person with your history, schooling, background, race, creed, color is going to be. And that has nothing to do with you, it has nothing to do with me,” he said.

“So you just have to stand firm and be the individual self that you are to fight through.”

Ridley, in The Reservoir, is coming to realize that “At some point, you gotta accept yourself. This is me, for better or for worse—not bitter, realistic rather—clear-eyed, mature, resolved.”

Just as the book’s protagonist finds respite in his Res: 365 art project, taking up David Duchovny’s The Reservoir may serve as an opportunity for self-discovery through the maze of make-believe.

Time lapses. Until it rises again. “The world is not a conclusion,” reminds Emily Dickinson. A resolution? “Invisible, as music. But positive, as sound.” That’s what she would tell Ridley.

***

David Duchovny’s previous novels include Truly Like Lightning,** *oly Cow, Bucky F\*cking Dent, and Miss Subways. As a musician, Duchovny has released three studio albums, Hell or Highwater, Every Third Thought, and Gestureland.*